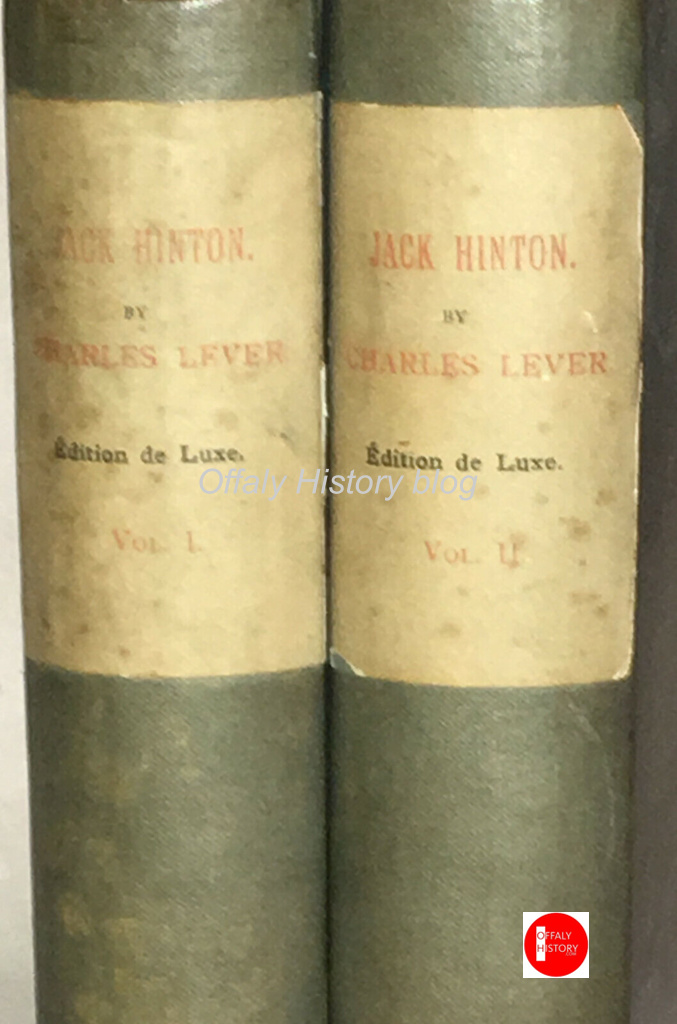

Charles Lever in his novel Jack Hinton sends his hero on a passage boat from Portobello (Rathmines, Dublin) to Shannon Harbour where he attempts to find accommodation at the hotel, then already in decay. Charles Lever began his Jack Hinton in the winter of 1841.

He had one chapter dedicated to ‘The Canal Boat’ and another to ‘Shannon Harbour’. He must have known the Grand Canal system well as John Lever, his brother, was rector of Tullamore from 1830 to 1843 and from 1843 to his death in 1862 at Ardnurcher (Horseleap). James Lever, their father, died at St. Catherine’s Rectory, Tullamore and was buried 1st April 1833. Charles Lever worked as a dispensary doctor at Kilrush and Portstewart and later in Brussels. He was back in Ireland as editor of the Dublin University Magazine (1842-45). His novels were attacked as stage-Irishry but his later novels have more sympathetic portrayals. It was during the early 1840s while resident in Dublin that Lever tried to ‘recreate the lifestyle of earlier generations of feckless Anglo-Irish gentry, becoming a semi-accomplished rider, hosting all-night card parties, and holding court in a Jacobean mansion in Templeogue, where he was visited by Thackeray, who dedicated his Irish sketch-book to Lever in 1843.’ (DIB online, entry by Jason King).

Charles Lever in his Jack Hinton (1843) describes the scene of his arrival at Shannon Harbour thus:

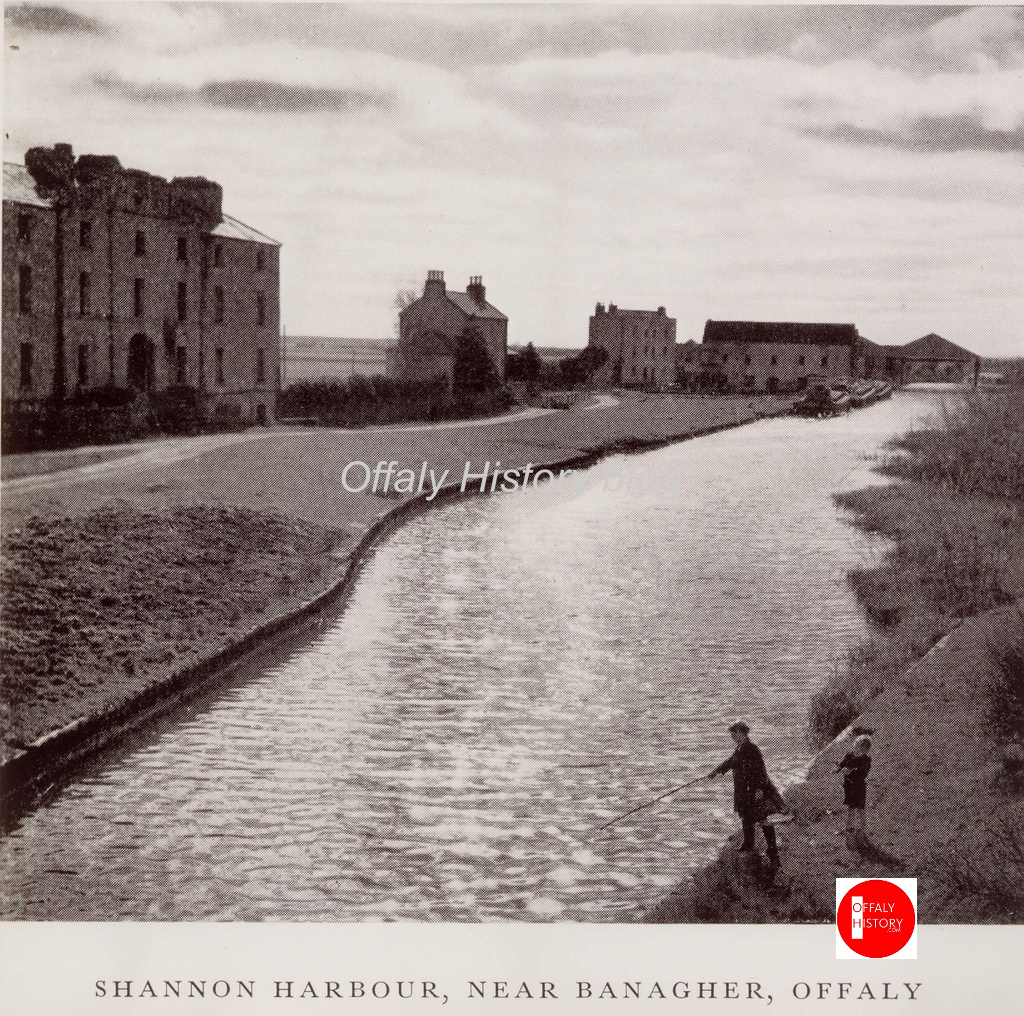

‘…the sedgy banks whose tall flaggers bow their heads beneath the ripple that eddies from the bow… the loud bray of the horn…the far-off tinkle of a bell. We near Shannon Harbour, and all its bustle and excitement. The large bell at the stern of the boat is thundering away…the banks are crowded…the track rope is cast off, the weary posters trot away to their stables, and the stately barge floats on to its destined haven without the aid of any visible influence. A prospect more bleak, more desolate, more barren it would be impossible to conceive – a wide river with low and reedy banks, moving sluggishly on its yellow current between broad tracks of bog or callow meadow-land; no trace of cultivation, not even a tree to be seen. Such is Shannon Harbour.’

Lever through the voice of Jack Hinton continues his description of Shannon Harbour:

‘No matter, thought I, the hotel at least looks well. This consolatory reflection of mine was elicited by the prospect of a large stone building of some stories high, whose granite portico and wide steps, stood in strange contrast to the miserable mud hovels that flanked it on either side. It was a strange thought to have placed such a building in such a situation. I dismissed the ungrateful notion, as I remembered my own position, and how happy I felt to accept its hospitality. A solitary jaunting-car stood on the canal side – the poorest specimen of its class I had ever seen; the car – a few boards cobbled by some country carpenter – seemed to threaten disunion even with the coughing of the wretched beast that wheezed between its shafts, while the driver, an emaciated creature of any age from sixteen to sixty, sat shivering upon the seat, striking from time to time with his whip at the flies that played about the animal’s ears, as though anticipating their prey.

‘Banagher, yer honour. Loughrea, sir. Rowl ye over in an hour and a half. Is it Portumna, sir?’

‘No, my good friend,’ replied I, ‘I stop at the hotel.’

Had I proposed to take a sail down the Shannon on my portmanteau, I don’t think the astonishment could have been greater. The by-standers, and they were numerous enough by this time, looked from one to the other, with expressions of mingled surprise and dread; and indeed, had I, like some sturdy knight errant of old, announced my determination to pass the night in a haunted chamber, more unequivocal evidences of their admiration and fear could not have been evoked.

‘In the hotel,’ said one.

‘He is going to stop at the hotel,’cried another.

‘Blessed hour,’said a third, ‘wonders will never cease.’

Short as had been my residence in Ireland, it had at least taught me one lesson – never to be surprised at anything I met with. So many views of life peculiar to the land, met me at every turn – so many strange prejudices – so many singular notions, that were I to apply my previous knowledge of the world, such as it was, to my guidance here, I should be like a man endeavouring to sound the depths of the sea, with an instrument intended to ascertain the distance of a star. Leaving, therefore, to time the explanation of the mysterious astonishment around me, I gathered together my baggage, and left the boat.

Scarcely had I put foot on shore, when the whole population of the village thronged around me. What are these, thought I? What art do they practise? What trade do they profess? Alas! their wan looks, their tattered garments, their outstretched hands, and imploring voices, gave the answer – they were all beggars! It was not as if the old, the decrepit, the sickly, or the feeble, had fallen on the charity of their fellow-men in their hour of need; but here were all – all – the old man and the infant, the husband and the wife, the aged grandfather and the tottering grandchild, the white locks of youth, the whiter hairs of age – pale, pallid, and sickly – trembling between starvation and suspense, watching with the hectic eye of fever, every gesture of him on whom their momentary hope was fixed; canvassing in muttered tones, every step of his proceeding, and hazarding a doubt, upon its bearing on their own fate.

‘Oh! The heavens be your bed, noble gentleman, look at me. The Lord reward you for the little sixpence that you have in your fingers there. I’m the mother of ten of them.’

‘Billy Cronin, yer honour. I’m dark since I was nine years old.’

‘I’m the ouldest man in the town-land,’ said an old fellow with a white beard, and a blanket strapped round him.

While bursting through the crowd, came a strange odd-looking figure, in a huntsman’s coat and cap, but both so patched and tattered, it was difficult to detect their colour.

‘Here’s joe, your honour’, cried he, putting his hand to his mouth at the same moment. ‘Tally ho! Ye ho!’he shouted with a mellow cadence I never heard surpassed. ‘Yow! Yow! Yow!’ he cried, imitating the barking of dogs, and then uttering a long low wail, like the bay of a hound, he shouted out, ‘Hark away! Hark away! ’and at the same moment pranced into the thickest of the crowds, upsetting men, women and children, as he went: the curses of some, the cries of others, and the laughter of nearly all, ringing through the motley mass, making their misery look still more frightful.

Throwing what silver I had about me amongst them, I made my way towards the hotel, not alone, however, but heading a procession of my ragged friends, who with loud praises of my liberality, testified their gratitude by bearing me company. Arrived at the porch, I took my luggage from the carrier, and entered the house. Unlike any other hotel I had ever seen, there was neither stir nor bustle, no burly landlord, no buxom landlady, no dapper waiter with napkin on his arm, no pert-looking chambermaid with a bed-room candlestick. A large hall, dirty and unfurnished, led into a kind of bar, upon whose unpainted shelves a few straggling bottles were ranged together, with some pewter measures and tobacco pipes; while the walls were covered with placards, setting forth the regulations for the ‘Grand Canal Hotel,’ with a list, copious and abundant, of all the good things to be found therein, with the prices annexed; and a pressing entreaty to the traveller, should he not feel satisfied with his reception, to mention it in a ‘book kept for that purpose by the landlord.’

I cast my eye along the bill of fare, so ostentatiously put forth – I read of rumpsteaks and roast-fowls, of red rounds and sirloins, and I turned from the spot resolved to explore further. The room opposite was large and spacious, and probably destined for the coffee-room, but it also was empty; it had neither chair nor table, and save a pictorial representation of a canal-boat, drawn by some native artist with a burnt stick upon the wall, it had no decoration. Having amused myself with the ‘Lady Caher,’ such was the vessel called, I again set forth on my voyage of discovery, and bent my steps towards the kitchen. Alas! my success was no better there – the goodly grate, before which should have stood some of that luscious fare of which I had been reading, was cold and deserted; in one corner, it was true, three sods of earth, scarce lighted, supported an antiquated kettle, whose twisted spout was turned up, with a misanthropic curl at the misery of its existence;

I ascended the stairs, my footsteps echoed along the silent corridor, but still no trace of human habitant could I see, and I began to believe that even the landlord had departed with the larder. At this moment the low murmur of voices caught my ear. I listened, and could distinctly catch the sound of persons talking together, at the end of the corridor. Following along this, I came to a door, at which having knocked twice with my knuckles. I waited for the invitation to enter. Either indisposed to admit me, or not having heard my summons, they did not reply, so turning the handle gently, I opened the door and entered the room unobserved. For some minutes I profited but little by this step; the apartment, a small one, was literally full of smoke, and it was only when I had wiped the tears from my eyes three times, that I at length began to recognise the objects before me.

Seated upon two low stools, beside a miserable fire of green wood, that smoked, not blazed upon the hearth, were a man and a woman, between them a small and rickety table supported a tea equipage of the humblest description, and a plate of fish whose odour pronounced them red herrings.’

Lever spent most of his time in Italy after 1845 and died in Trieste in 1872 where he completed his finest work Lord Kilgobbin. His wife and a son had predeceased him. His last years were filled with sadness.