At the opening of the nineteenth century Edenderry was said by one observer to soon ‘be a heap of ruins.’[i] The new Grand Canal was expected to bring relief to Edenderry and the surrounding hinterland. In the aftermath of the 1760s economic downturn in the woollen industry Edenderry suffered greatly having once employed 1,000 workers in the trade.[ii] The Downshire estate in the town and surrounding hinterland consisted of 14,000 statute acres of land.[iii]

The linking of Edenderry to the canal was of economic necessity in the last decade of the eighteenth century. As Ciarán Reilly explains:

‘Without the Grand Canal, Edenderry in the nineteenth century would have not as prospered as it did, the canal providing a much needed communication network and transportation for goods such as peat, corn and flour to Dublin.’[iv]

Charles Vallancey believed ‘the peasantry are starving and nothing will contribute so much to their relief as the Inland Navigation.’ John Hatch, as Edenderry agent for the Blundell estate was aware of the potential for economic progress of the Grand Canal for the town. (5 W. A. Maguire, ‘Missing persons: Edenderry under the Blundells and the Downshires, 1707-1922’ in William Nolan and Timothy P. O’Neill (eds), Offaly: History & Society (Dublin, 1998), pp 515-542 at p. 524.)

In June 1787 Hatch alerted the Blundells that it was confirmed the canal would pass near Edenderry:

‘… by this resolution of the company everything will rise again and higher than ever and I have not now the smallest doubt of our going on with the canal to or near Edenderry.’[vi]

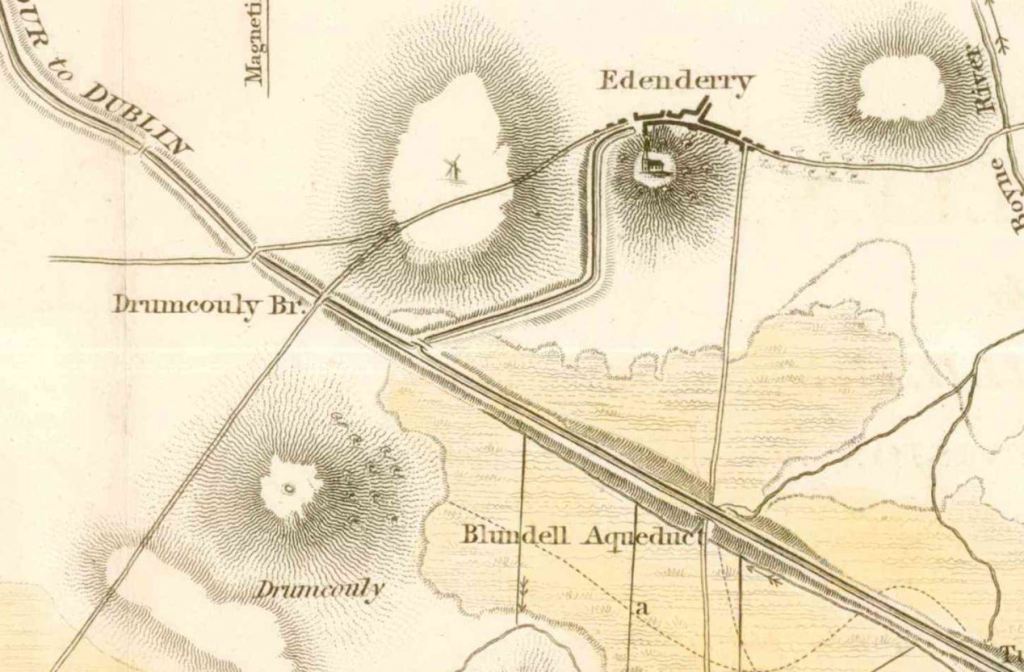

From 1790 work on the drainage between Tickneven and Edenderry proved difficult. A Captain William Evans, one of the Company’s directors, wrote of the subsidence on either side of the canal making work slow. The subsidence problem would bring trouble frequently due to the topography of the surrounding peat bog. Lord Downshire gave financial support to the project to keep it afloat, seeing the economic opportunities it would bring to his property in Edenderry.[vii] The canal passed within two kilometres of the town of Edenderry when the line was finally completed in 1796.

Work on a branch line into the town of Edenderry began in 1797 but was halted in 1800 due to a break in the bank west of the Blundell Aqueduct. Following this, Downshire’s agent, James Brownrigg, appealed to the board to get the canal and harbour complete while ‘the men and materials were at hand,’[viii] it would still be another two years before the harbour opened. In 1801 the second Marquess of Downshire died and the estates of his family passed to his wife, Mary Sandys, and from 1809 to her son Arthur Hill, third marquess.[ix] By September 1802 the harbour was complete and operating at a final cost of £692. The Company financed the hump-backed bridge, known as the Downshire Bridge, for £55. It was built where the spur diverts the canal itself to allow the horses to be taken across to tow the barges.[x]

Edenderry Harbour, 1971 (Waterways Ireland, Delany Photographic Collection, RDCG11003)

Travelling by boat on the canal was a common sight from the 1800s until the 1850s when it was closed to passengers and thereafter was used for the movement of goods only. Pigot’s Trade directory (1824) notes two boats to Dublin and Tullamore operating daily at Edenderry in 1824.[xi] Fly-boats were known to stop at Blundell Aqueduct and Colgan’s Bridge where a rest-house was available for passengers. The fly-boats commenced running in 1834 and with an average speed of 8 mph. During the day these fly-boats would operate and the slower iron boats were in service at night. One such iron boat is recalled by a Jonathan Binns in 1837 as ‘spacious and conveniently fitted up’ and another critically by Mr and Mrs Hall in the 1840s who complained ‘the boat being exceedingly narrow, the passengers are painfully “cramped” and confined.’[xii]

The canal played its own part in the Irish rebellion of 1798 being used by the Irish rebels and the military to transport men and weapons. During 1797-98 supporters of the Irish Rebellion were operating smuggling operations along the canal. Among them were canal workers, causing other canal employees and local farmers to form a corps of yeomanry in Edenderry.[xiii] Upon the Irish-French defeat at the Battle of Ballinamuck on September 8th 1798 the French prisoners of war were sent to Dublin, where along the canal banks locals gathered to see the boats pass as the Frenchmen sang La Marseillaise.

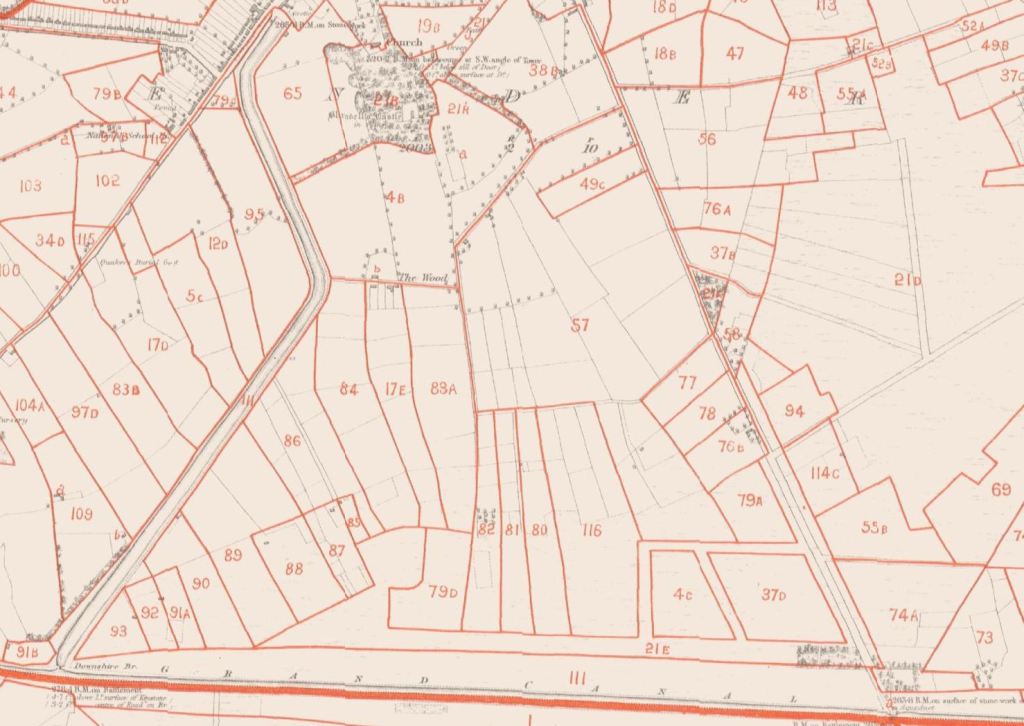

During the third Marquis’ ownership of Edenderry a large project of stone building in the town, 1809-45, brought with it local manufacturing which raised the position of Edenderry quite unlike that which it had been in the 1780s before the canal’s arrival. By the 1820s the value of land along the canal had almost doubled.[xiv] In 1853 Griffith’s Valuation listed the Grand Canal Company as owning 72 acres with a rateable value of £844s 0d in Edenderry townland along the canal from the harbour down to the Downshire Bridge and across east to Blundell Aqueduct. On the south bank of the canal in Drumcooly townland the Company owned 32 acres with a rateable value of £27 16s 0d.[xv] An Irish Constabulary barracks was erected close to the harbour and in proximity to the town centre in order to control the movement of goods on the canal.[xvi] There was also a need to prevent theft at night of goods sitting in the harbour. James Brownrigg, Downshire’s agent, reported in 1817 that ‘mobs’ were plundering the provisions of boats along the Edenderry line of the canal. Such mobs likely being the impoverished of the town without employment. He further placed a military guard at Blundell Aqueduct to prevent its destruction.[xvii] In 1831 Edenderry was described in a letter to Lord Downshire as ‘very clean, and several of the poor peoples houses have been washed with lime, and [I] am happy to inform your Lordship that the Town is free from Fever.’[xviii]

Downshire’s improvements in the town were evidenced in 1837 by Samuel Lewis’ Directory, which noted Edenderry had over two hundred houses built of stone and were slated and ‘is rapidly improving.’[xix] The Irish Parliamentary Gazetteer of 1845 noted the principal business of the town is in the trading of corn along with tanning and coarse woollen manufactures. Edenderry had a population of 1,439 in 1821.[xx] In 1831 the town itself had a population of 1,283.[xxi] The population of the town of Edenderry in 1841 was 1,850 with 255 houses. It would appear that by 1841 the economic condition of Edenderry had improved with an increase of 567 persons. Giving evidence to the Devon Commission, Robert McComb, who farmed 80 acres close to the town, stated there had been no agrarian outrages on the Downshire estate ‘for years back.’[xxii] These assessments however do not take into account the continued poverty and misery of the majority of the people of Edenderry which would deteriorate further with the arrival of the Famine in 1845.

After the Edenderry branch of the canal was finished construction it finally reached Tullamore in March 1798, linking transportation and communication between eastern and central King’s County. By the 1850s the canal had served its personal transport purposes owing to the development of road and rail traffic in King’s County. Subsidence remained a problem for the Edenderry line of the canal throughout the early decades of the nineteenth century and well into the late twentieth century. In closing, the Grand Canal was central to the economic development of the town of Edenderry and its surrounding environs in the nineteenth century as it brought industry and commerce that it otherwise would not have benefited from.

[i] Charles Coote, Statistical survey of King’s County (Dublin, 1801), p. 121.

[ii] Mairead Evans and Therese Abbott, Safe harbour: The Grand Canal at Edenderry (Edenderry, 2002), p. 9; Ciarán Reilly, The Irish land agent, 1830-60 (Dublin, 2014), pp 27-8

[iii] Edenderry Historical Society, The influence of Lord Downshire III on the Downshire estate at Edenderry (Edenderry, 1996), p. 2.

[iv] Reilly, Edenderry, 1820-1920: Popular politics and Downshire rule (Dublin, 2007), p. 45.

[v] Evans and Abbott, Safe harbour, p. 9.

[vi] Evans and Abbott, p. 10.

[vii] Evans and Abbott, p. 10.

[viii] Ruth Delany, The Grand Canal of Ireland (Newton Abbot, 1973) p. 46.

[ix] Reilly (intro.), Old Ordnance Survey map: Edenderry 1911 (Leadgate, Consett, 2011), p. 1.

[x] Evans and Abbott, p. 11.

[xi] Pigot & Co’s Provincial directory of Ireland 1824 (London, 1824), p. 150.

[xii] Evans and Abbott, p. 19-20.

[xiii] Delany, The Grand Canal, p. 71.

[xiv] Evans and Abbott, p. 22.

[xv] Richard Griffith, General valuation of rateable property in Ireland: King’s County (Dublin, 1853), pp 30, 26.

[xvi] Reilly (intro.), Old OS map, p. 3; Edenderry Historical Society, The influence of Lord Downshire III, p. 25.

[xvii] Evans and Noel Whelan, Edenderry through the ages (Edenderry, 2000), p. 38.

[xviii] ‘Francis Farrah to Lord Downshire, 26 December 1831’ in W. A. Maguire (ed.), Letters of a great Irish landlord (Belfast, 1974), pp 83-4.

[xix] Samuel Lewis, An A-Z of Offaly in 1837 (Tullamore, 1999), p. 51.

[xx] Michael Byrne, ‘Economic development in Offaly’s towns and villages in the eighteenth century and the Vallancey Survey of 1771’ in Offaly Heritage, vol. 4 (2006), pp 95-166 at p. 115.

[xxi] Census of Population of Ireland, 1831; Comparative Abstract, 1821 and 1831, H.C. 1833, xxxix, p. 7

[xxii] Evans and Whelan, p. 41.