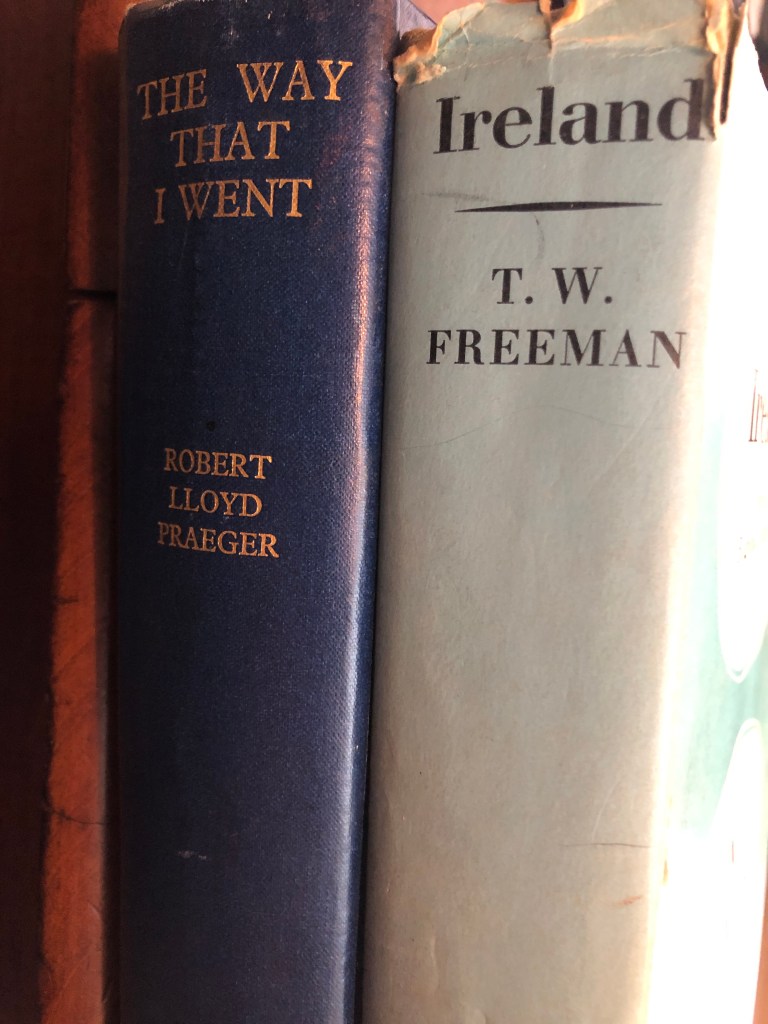

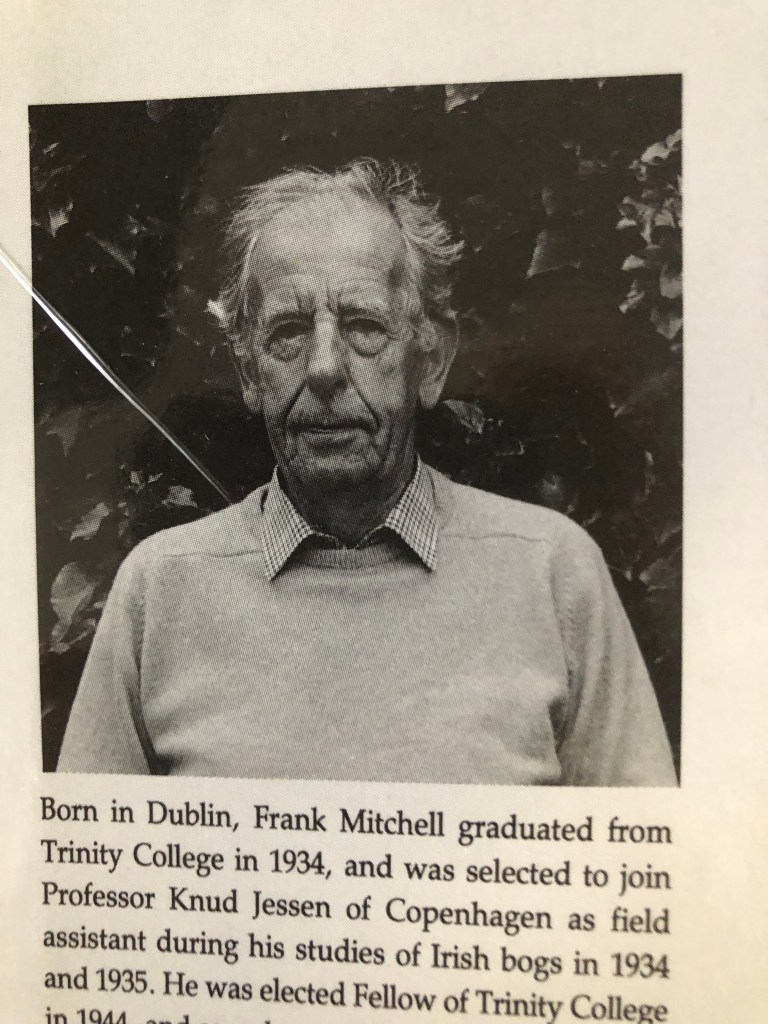

Frank Mitchell (1912–97) was a distinguished but unassuming academic, environmental historian, archaeologist and geologist. While he had many academic writings his best known book was The Irish Landscape (1976) about which he was typically modest. In 1990 Mitchell published ‘a semi-autobiography’ The way that I followed. The title was a play on Robert Lloyd Praeger’s, The way that I went (Dublin, 1937). A delightful exercise in ‘topographical autobiography’. Praeger in his peregrinations was less kind to Laois and Offaly than Mitchell with Praeger’s observation that ‘neither county need detain us long’ (p. 235) and ‘there is not much of special interest’ (p. 237). Westmeath he found to be more hospitable than Offaly having less than half of the amount of bog in Offaly and more pasture. We may look at the Praeger account in another blog. Suffice to say that bogs were not flavour of the month with the visitors from the 1800s to the 1930s and who wrote up accounts of their tours. Mitchell did not follow that century old prescription.

Someone who Mitchell would have known (at TCD) and admired was T.W. Freeman. The latter’s Ireland a general and regional geography (1950, third edition, 1963) provided a useful account of the boglands east of the Shannon and the eskers of the Central Lowland with a brief disquisition on the market towns ‘that differ so strangely in their material prosperity’. Freeman was fascinated by the unexpected and haphazard nature of economic life in some of the towns – he seems to have had in mind Tullamore and Clara.

In any case let us go back to look at what Mitchell wrote of the terrain east of the Shannon as part of this Grand Canal series.

From The way that I followed, pp 210–33.

The Shannon

At Athlone we have left the drumlins far behind, and are now in esker country. When an ice-sheet is melting away, great quantities of water are set free at the base of the ice. Discharge tunnels gradually develop to carry away water, sand and gravel, and if the main flow of water changes direction, a tunnel may be abandoned, and gradually silt up with sand and gravel. When the ice finally disappears a cross-country ridge of sand and gravel, an esker, is revealed.

From Athlone south to Meelick, a distance of 30km, the river approaches, or cuts through, several eskers. Such places obviously offered crossing-points, and they have been used by people, certainly since Bronze Age times.

Athlone

At Athlone an esker is cut through by the river, and the crossing here has been of high strategic importance down the ages. The main point of defence has always been on the west bank, to guard the bridge leading to the east. The Normans built a strong castle in the early thirteenth century, and this has been the nucleus of fortification ever since. There was fierce fighting here in the Williamite war, and the nineteenth-century threat of French invasion led to a further strengthening of the approach to the river by building forts and redoubts a little further to the west. We shall find splendid examples of nineteenth-century fortification all the way to Meelick.

The Shannon shallowed as it crossed the gravel ridge, and a ford long preceded the bridge. Later excavations to improve navigation produced many Bronze Age finds, and such finds have been supplemented by the activity, both legal and illegal, of sub-aqua divers. A splendid Bronze Age shield, rivalling that from Lough Gur, was recently found by divers. In the eighteenth century a canal with small locks was cut to the west of the town, but this had become virtually impassable by the early nineteenth century. The Shannon Commission then stepped in, and in the early 1840s rebuilt the road bridge and constructed a large lock, 38m X 12m, as part of their programme to open up the river for steamboat services.

Mongan Bog, still relatively intact, and now protected, lies between eskers. Fin Lough, a still uncovered remnant of former widespread lakes, survives beside Blackwater Bog, almost destroyed by development. The Clonfinlough Stone is nearby.

Clonmacnoise

We drop down from Athlone to Clonmacnoise on a broad river flanked by hay-meadows which are often flooded in winter. If the season is right we will be serenaded by corncrakes as we go, as these late-cut meadows are one of their last refuges in Ireland. Behind the meadows we see raised-bogs, with low farmland rising beyond them. Clonmacnoise is of course a very historic site, with one of Ireland’s most important early Christian monasteries, with high crosses and round towers. It was plundered by the Vikings around AD 800, and again by the Normans, though the latter did add Romanesque churches as well as a castle. The monastery was destroyed in Elizabeth times, and the castle was slighted by the Cromwellians.

My interest here is chiefly environmental, an interest greatly augmented by the work of a study group drawn from the environmental Services Unit of Trinity College, and the County Offaly Vocational Educational Committee, who carried out a detailed study and proposed that the area should become a Heritage Zone. Such a zone is ‘a defined area with sufficiently rich inventory of heritage items to warrant a concerted and coordinated approach to conservation’. The Clonmacnoise area certainly comes within such a definition.

We had here at the end of the Ice Age a series of eskers, and the monastery was sited at the point where two eskers converged and then turned south along the east bank of the river. Roadways ran along the crest of the eskers, and this meant that the monastery had good communications. The northern esker carried ‘the Pilgrims’ Road’, an important route through the midlands.

Immediately after the esker had formed, the huge lake, to which I have already referred, flooded the area, covering great tracts of land, and on the floor of the lake, whose waters were still icy cold, deposits of sterile gray clay were laid down. As the temperature rose, plants and animals invaded the lakes waters. The water was rich in dissolved calcite, and algae such as Chara deposited a limy ooze on the lake-floor in which the shells of freshwater molluscs were incorporated to form shell-marl. As the water shallowed, fen-plants invaded the margins of the open water, and the lake began to be transformed into the river-channel we see today. Fen-peat began to accumulate, and as this thickened nutrient supplies for plant-life fell away, and gradually the plants of the fen gave way to those which needed very little inorganic nutrient for their growth, and raised-bogs began to build themselves up on top of the fen.

At Clonmacnoise an arm of the lake was trapped between two eskers, and here today we have an almost raised-bog, Mongan Bog, whose conservation for the benefit of posterity is of the greatest importance. If we make a boring in the bog, we can go backwards in time through the events outlined in the preceding paragraph, and trace the history of forest development and subsequent disappearance in the Shannon basin. We also get an insight into the activities of early peoples.

Across the esker on the south side of Mongan Bog, we come to small patch of open water, Fin Lough, a tiny successor of the former great lake, trapped between the esker to the north and another raised-bog, Blackwater Bog, now largely destroyed by commercial peat-winning, to the south. Here alkaline water flowing out of the esker has enabled fen-vegetation to survive, and so this patch avoided being swallowed up by bog. The complex habitat, an intimate mixture of open water and fen, enables a wide range of plants to flourish, and these in turn provide breeding ground for residential birds, while the open water gives refuge to migrating swans, geese, ducks and waders. As an ecological unit, Fin Lough very prettily complements Mongan Bog, bringing together two types of rich habitat now becoming all too rare, not only in Ireland but throughout western Europe. It was therefore most appropriate that the recent study should have been funded in part by the European Economic Commission.

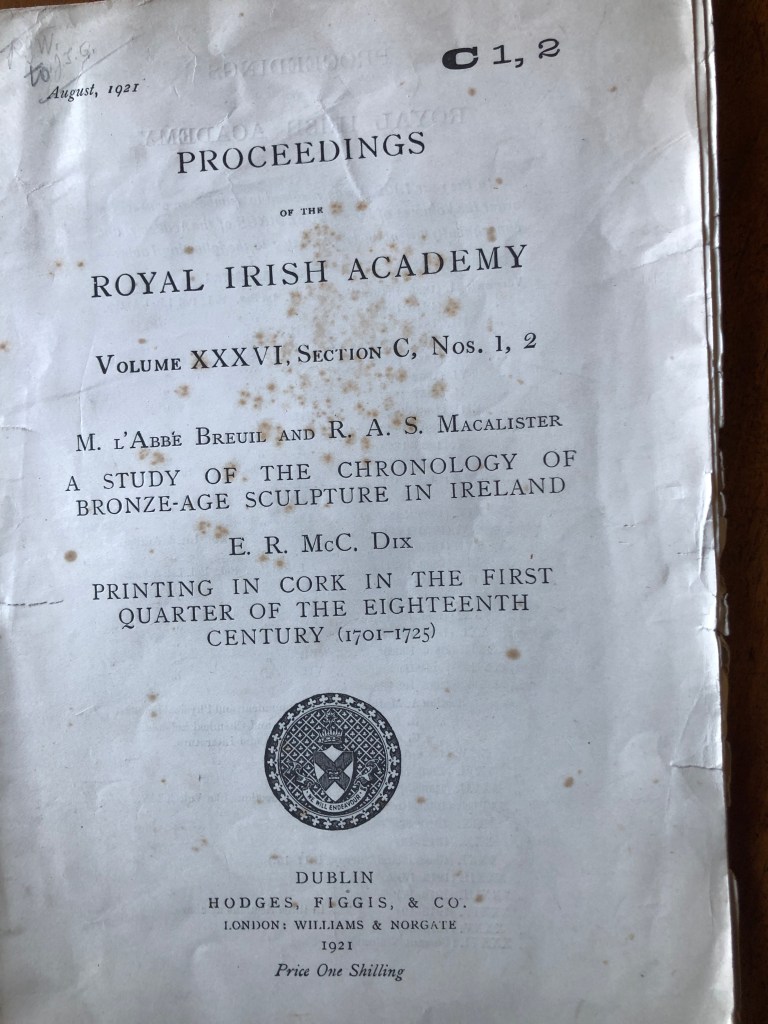

A short distance to the east of the lough we find the Clonfinlough Stone, a large erratic boulder of sandstone, which carries enigmatic designs, part natural, part improved on by man, probably in Bronze Age times. I have been present on many interesting occasions, such as the discussion on the bog at Roundstone, but one I missed was the examination of the stone by R.A.S. Macalister and the Abbé Breuil.[1] We have already met Macalister. He had a fertile imagination, but he met his match in the Abbé Breuil, one of the landmark figures in European archaeology. As Praeger recounts, Breuil had been examining Spanish cave-paintings just before his Irish visit, and claimed that the Clonfinlough scribings were an exact analogue of these. I only spoke to the Abbé once, when he was over ninety years of age, but I should have loved to have been Clonfinlough with a tape-recorder, and preserved for posterity the far-fetched and excited dialogue that must have taken place.

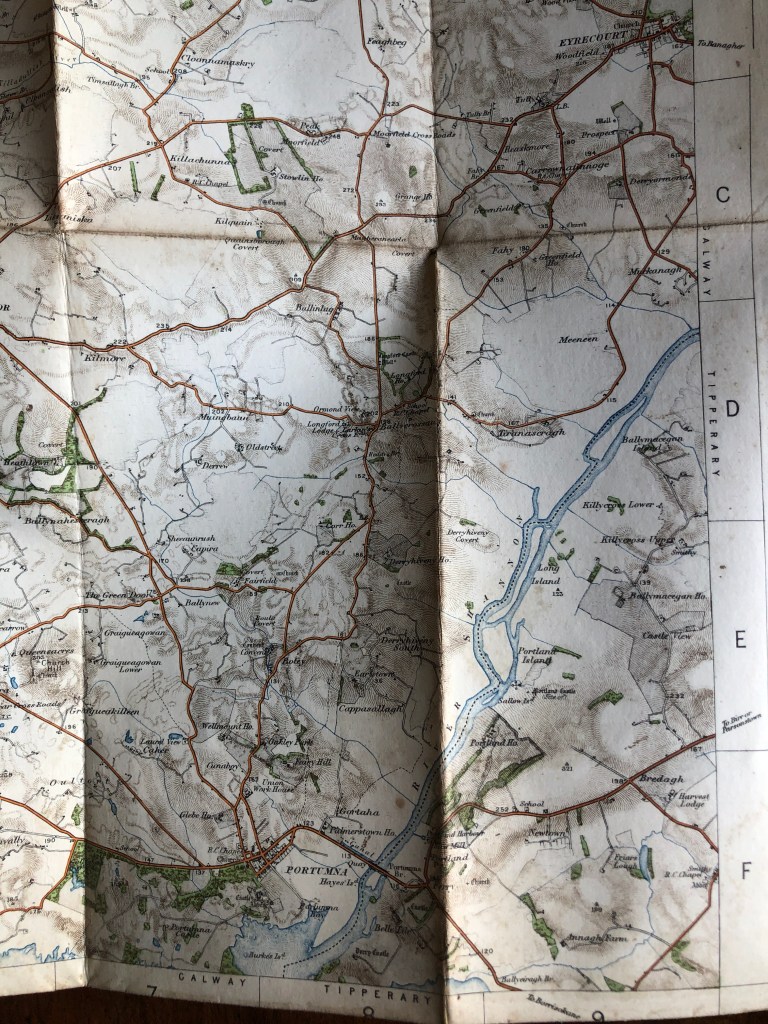

From Clonmacnoise we drop down to Shannonbridge, where the esker that has lain on the east bank of the river turns wet and crosses it, and so provides a route to Ballinasloe. There is a fine early eighteenth-century bridge here, and on the west bank yet another very strong anti-Napoleonic block-house with supporting buildings. The buildings are still virtually intact today, and could well be restored as a tourist attraction.

Here we are surrounded by raised-bogs on all sides, and these are being vigorously exploited to feed a power-station at Shannonbridge. Work preliminary to development showed that the bog areas are underlain by sterile grey clay, further evidence of the former enormous lake in the basin of the Shannon.

From Shannonbridge we drift down to the point where the River Brosna joins the river from the east. If we were to exchange our cruiser for a canoe, we would follow the Brosna north-east upstream to Ferbane, and then turn south down its tributary, the Silver River, to Boora, where we would meet another peat-fired power-station. A short distance across the bog, we would come to Lough Boora which, like Fin Lough, is a surviving fragment of the former lake.

Boora

When a bog is exploited, a small thickness of peat is usually left undisturbed at the bottom of the bog. Unfortunately bog-exploitation results in large quantities of finely divided peat being carried away in the drainage water, and the water reaches rivers with fish in them, the peat clogs the gills of the fish with disastrous results. At Boora the Bord decided to construct settling ponds to retain the peat fragments. This involved the stripping away of all peat in order to excavate the ponds in the basal glacial material. Such stripping revealed a gravel ridge on which early hunters had camped about 8500 years ago, about the same time as the occupation of the site at Mount Sandel near Coleraine, which we have already visited. Parallel to the ridge, but a little distance from it, was a line of storm beach gravels, built up by the waves of the former lake. This is the best proof I know of the former existence of the big lake. Its waters must have been wide enough for strong winds to whip up considerable waves, when the waves reached the shore, they built up a substantial storm beach. There would have been a lagoon between the beach and the ridge, and obviously the top of the ridge, overlooking the lagoon with its ducks and its fish, would have provided a very attractive site for early hunters.

We return to our cruiser, and after a few metres turn sharp left into the mouth of the Grand Canal, which finally reaches the Shannon at this point. When I was there in 1988 the canal-banks had been scraped down not long before, and showed a fine section of the basal grey clay of the former lake passing up into shell-marl. If we continue a short distance up the canal, passing through two locks as we do so, we come to Shannon Harbour, rather sad with derelict docks and hotel, the former terminus of the Grand Canal. We turn downstream, and quickly come to Banagher, an attractive village with some fine Georgian houses and a splendid bridge, built by the Shannon Commissioners, it also has associations with Charlotte Bronte and Anthony Trollope. The river skirts the east end of an esker, and there was a crossing-point here, which was fought over many times, just as at Athlone. Some little distance back from the river on its western side there is a splendid round nineteenth-century fort, rather like a giant Martello tower.

Meelick

Six kilometres downstream, we come to Meelick, one of my chief problem points on the Shannon. Here a more resistant block of limestone confronts the river, yet the river is not diverted, but cuts across it, breaking down into smaller channels as it does so. The river is at 37m above the cut, and the rock rises to 50m on either side of the cut. The site has been a strategic one for a long time, the earliest fortification being a Norman castle built in 1203, and the latest, anti-Napoleonic block-houses dotted here and there.

The Grand Canal Company carried their route with several locks on the east side of the river, but the Shannon Commissioners went straight through with a rock-cut channel leading to the largest lock on the river, 43m long. It is built of splendidly fitted stone, with its name ‘Victoria’ cut in larger letters on one side. The lock projects like the high bow of a large boat into the lower ground downstream, and the view south is one of the most dramatic on the river. Below to the west are the partly restored remains of a Franciscan abbey, founded in 1445. Although it is almost inaccessible by road, the site is well worth a visit, as the graveyard round the church has the finest collection of beautifully lettered seventeenth-century gravestones that I know.

Whereas in other parts of its course the Shannon is obviously in a ‘young’ channel, controlled by the local glacial deposits, I feel that at Meelick the channel across rock must be ‘old’, and that the river maintained its course across the limestone block, while the surrounding country was being lowered in level by erosion. We shall meet the same problem at Castleconnell, below Killaloe.

As we emerge from the lock we have the exit of the old canal and the mouth of the Little Brosna River on our left. Here in winter there is often extensive flooding of the riverside meadows, or callows, as they are called, and the flooding extends far up the Little Brosna. The flooded callows provide wonderful winter feeding for geese, ducks and waders, and an observation hut provided by the Irish Wildbird Conservancy half-way between Birr and the Shannon gives splendid viewing of these birds. In addition many waders breed here during the summer, including black-tailed godwit, which have their only Irish breeding-station here. In all a most successful raid, but perhaps not yet the end of the story. In1986 Russell investigated, in a sand-pit in Shropshire, the discovery of an adult, and also, almost incredibly, three infant woolly mammoths. Here the radiocarbon age was 12,700 years, showing that mammoths were still around 5000 years after they were supposed to have become extinct. The age of 12,700 is not too wildly far from the Drumurcher date 10,500. I feel we should go back again, and work up along the base of the water-wall of the mill, seeing if we could recover even one scrap of identifiable bone. With modern advances in radiocarbon dating, one quite small piece would be sufficient.

[1] For more on this meeting see Praeger, The way that I went, pp 239-40.