Growing up in our house in Clonminch outside of Tullamore, I came to detest

that mawkish dirge about the Lake Isle of Innisfree. My grandfather, who had

once visited the island, was obsessed by the poem and insisted that I recite it

at every party. He even named our house after it.

Later, as a young town planner, I blamed the wretched verse for the rash of

holiday homes that were beginning to appear in every beauty spot in Ireland

and cursed Yeats who had provided the moral justification for this desecration.

If a well known poet could simply arise and go and build in whatever idyllic

place he chose, why shouldn’t everybody else?

But – would Yeats get planning permission? I would put that to the test.

Having never seen Innisfree and having no intention of ever setting foot on it, I bought an Ordnance Survey map and drew a traditional clay and wattled

Irish cottage slap bang in the middle of the island. I surrounded it with nine

bean rows and a hive for the honey bee- or several honey bees, if it came to

that. I had thought of providing nests for the linnets but not being fully au

fait with the necessary ornithological arrangements, I decided to leave the

linnets out.

Now, in those days there were loopholes in the Planning Act which allowed

you to make an application on property which you didn’t own – nor did you

have to put up a site notice. So, I had all I needed to make a valid application

to Sligo County Council who would have to deal with it whether they liked it or not. I sent off my package and having lit the blue fuse, retired to a safe

distance to watch the fun.

Recently, I obtained the internal reports of the Council’s Planning Section

which were professionally objective and surprisingly didn’t reflect the irritation of busy officials who most likely thought they had better things to be doing than dealing with a crank or a comedian.

The planning application was referred to the Arts Council for advice and its

Secretary, the writer Mervyn Wall, replied. Wall noted the similarity of my

proposal to the cemetery of Whispering Glades in Evelyn Waugh’s satirical

novel The Loved One which had reserved an area containing a small cabin,

bean rows and beehives solely for the interment of writers and, anticipating

the ridicule which the Council would endure in the event of a grant, urged the

rejection of my application.

My application was also referred to the architectural historian Maurice Craig

for comment who, in the spirit of the exercise, wrote a spoof report suggesting

that the bearing strength of clay and wattles might be more than expected and

that the proposal could be a stalking horse for a much taller building.

Two months later I received a refusal set out in impenetrable bureaucratic

planning speak. To copper fasten it, on April Fool’s Day 1971, I lodged an

appeal with the Minister for Local Government and six months later, to my

delight, he turned me down too.

So, having put a stop to Master Yeats cabin building ambitions, I was content

at last.

Long, long after I had forgotten the whole silly episode, the young Sligo artist

Clea van der Grijn rang me out of the blue to ask if there was any truth in the

legend she had heard that someone had once tried to make Yeats’s dream

come true. I explained that the exact opposite was the case and to my

surprise found myself caught up with an enthusiastic group of local artists,

architects and poets who wanted to honour the hundred and fiftieth

anniversary of the poet’s birth by responding in their own, non interventionist,

ways to his mythic island.

Thus, on a surprisingly still and bright January day, I found myself standing

with them on the island of Innisfree.

A tiny untouched knoll, quite close to the shoreline of Lough Gill and covered

in holly and oak, it rises up from the landing place on its eastern shore to a

slight hill on its western and northern sides from which stunning views up the

lake towards Sligo town are revealed.

It is a child’s dream of a desert island – big enough to get lost in and yet small

enough to be found again. From the western bluff you can actually hear the

sound of lake water lapping on the shore below. It is a very special and

romantic place and only the most insensitive developer (and certainly not a

poet) would think of placing a holiday home in the middle of it.

I was instantly won over and fell in love with it as Yeats and my grandfather

once had.

I don’t believe for a moment that the poet actually wanted to build

a holiday home on the island – indeed he never lived in Sligo afterwards and

sensitively restored a castle in Galway. But standing on the little hill, I gave

thanks for those convoluted and torturously worded planning refusals which

had long ago conclusively protected Innisfree.

We give out a lot about our planning system these days but, should we ever

find ourselves in exile and far from home, we can still recite the words of ’The

Lake Isle’ and know that a very special place where all our troubles will

vanish is still unspoiled and still waiting for us.

Just don’t try to build a cabin – please.

Fergal MacCabe

The Lake Isle of Innisfree

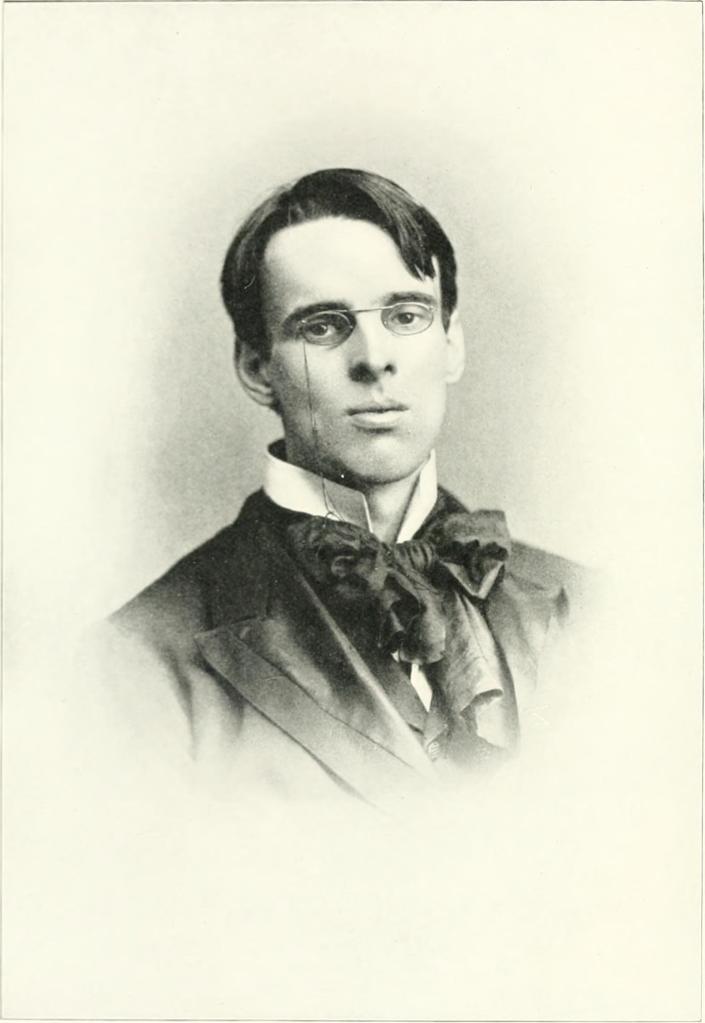

(W. B. Yeats 1865 – 1939)

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee;

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.