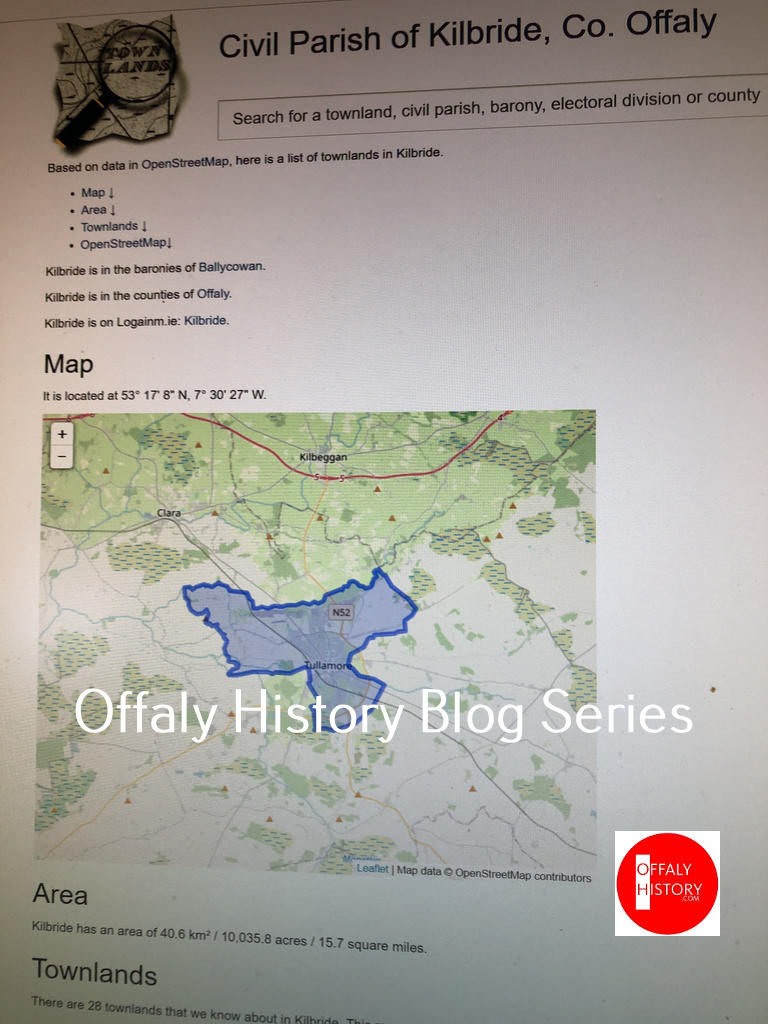

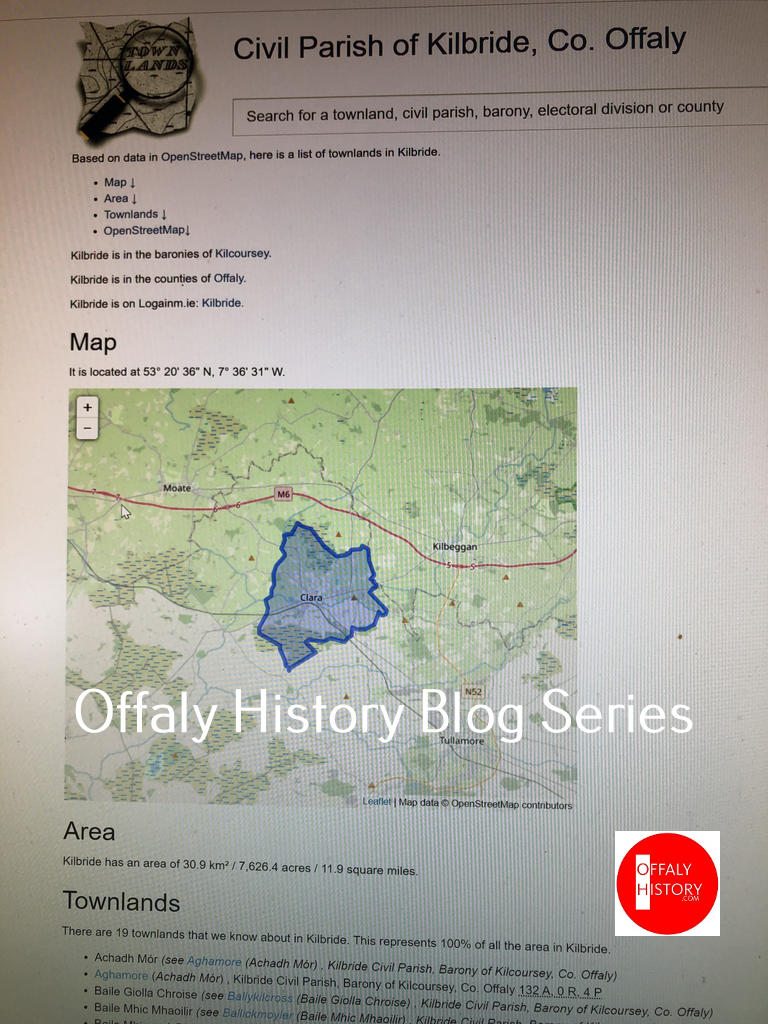

Tullamore is situated in the civil parish of Kildbride with 28 townlands and so too is the town of Clara with 19 townlands. Both parishes have a connection with the churches dedicated to Saint Brigid. Now Ireland mark the saint’s day on 1st of February with a public holiday, the beginning of spring and the celebration of Lá Fhéile Bríde, St Brigid’s Day.

These are the only townlands in Offaly dedicated by name to a church associated with Saint Brigid.

Kilbride (Cill Bhríde) , Kilbride Civil Parish, Barony of Ballycowan, Co. Offaly 193 A, 3 R, 20 P

Kilbride (Cill Bhríde) , Kilbride Civil Parish, Barony of Kilcoursey, Co. Offaly 146 A, 2 R, 30 P

The proximity of the two parishes often leads to confusion especially when tracing soldiers of the First World War who gave their place of birth as the civil parish of Kilbride without distinguishing wherether it was Clara or Tullamore.

To the east of both towns is Croghan Hill associated by some scholars with the birthplace of St Brigid. John O’Donovan was well aware of the association of the hill with the legend and cult of St Brigid and wrote of it in the Ordnance Survey letters. The Ordnance Survey Letters for County Offaly form part of a countrywide series, are commonly known as O’Donovan’s Ordnance Survey Letters.

The Ordnance Survey Letters for Offaly of 1837-1838 represent the first attempt on a systematic basis to collect material on Offaly’s historical and archaeological remains. The pioneering effort of the Ordnance Survey and of its topographical department, in particular, was not emulated until the publication some 150 years later of the Archaeological Inventory of County Offaly by Caimin O’Brien and P. David Sweetman. O’Donovan’s Ordnance Survey Letters are in manuscript form in the Royal Irish Academy and were published in a typescript by Fr. Michael Flanagan in 1933. The late Professor Michael Herity edited the volume of letters for Offaly and this book is available from the Society and can be ordered online at our shop at www.offalyhistory, or consulted at Offaly History Centre.

The Offaly material consists of fifty-one letters of John O’Donovan and of Thomas O’Conor. O’Conor, a native of Carrickmacross, was assistant to O’Donovan. Both men had spent September, October and November of 1837 in County Westmeath and in late December of 1837 their attentions turned to Offaly, then and until 1920 called King’s County. The letters concern local antiquities, placenames, early Irish history and the genealogy of the native families

It should be noted that in the Westmeath letters volume are one of John O’Donovan’s from Tullamore and another from Edenderry. That from Tullamore is dated 1st January 1838 and could properly be in the King’s County volume. A list of the fifty-one letters concerning King’s County written over the period from 18 December 1837 to 11 February 1838 with the inclusion of two letters about Durrow, that of October 1837 and the second written on 1 January 1838.

O’Donovan wrote of the legends associated with St Brigid as follows:

St. Briget was consecrated a Bishop.

(Father Bollandus complains of the silliness of the writers of the lives of the Celtic Saints; and the Benedictines complain of the folly even of St. Jerome and Augustin!.)

“Bridget was desirous that a degree of Penance (gradh Aithrighe) should be conferred upon her. Hearing that Bishop Mel was at Bri Éle (Croghan old Church) she repaired thither, accompanied by seven nuns. But on their arrival the Bishop was not there, but had gone into the Country of the Hy Niall “terra nepotum Neill” (Meath). On the morrow she passed in search of him in company with Mac Caille (the Bishop of Brig-Ele) who guided her over the bog of Monaidh Fathing, which she converted into a flowery plain. When they had come close to the Town (baile) where Bishop Mel was, Briget told Mac Caille (Macaleus) to put (place) a veil on her head, that she did not wish to appear unveiled before the clergy. Upon her arrival a pillar (column, a glory?) of fire sprung rose, shot out) from her head, reaching even to the roof of the church. When Bishop Mel had seen this, he asked: “Who are the Nuns”? Mac Caille answered: “This is Briget, the celebrated Nun of Leinster.”

“My affection to her, said Bishop Mel, it was I who predicted her greatness, even while she was in her mother’s womb, and it is I who will confer orders on her.”

“This (gloss) alludes to one occasion that Bishop Mel came to the house of her father, Dubhthach; he saw the wife of Dubhthach grieved and sorrowful, and he asked whence the cause of her sorrow. I have cause of sorrow, said she, for Dubhthach admires (loves) the handmaid who attends. This is just (meet, dethbhir) said Bishop Mel, for thy seed shall serve (obey) the seed of this handmaid, alluding to Bridget.” (Bridget was illegitimate, but not the worse Bishop for that, and —-).

“Then Mac Caille placed a veil (caille, cowl) on the head of Briget. Wherefore, from that day to this, the Coarb (successor) of St. Briget (Abbess of Kildare) is entitled to receive the grade (dignity, orders) of a Bishop.”

“Wherefore have the Nuns come? said Bishop Mel. To have orders of Penance conferred on Bridget, said Mac Caille. Then he conferred orders on Briget, and it was the orders of (gradha eps.) a Bishop, that Bishop Mel conferred upon her!”

(Columbkille intended to get himself made a Bishop, but the Consecrator made him only a Priest by mistake. The authorities of the Irish Bulls Begins with Brian Boru).

“While St. Briget was being ordained, she held the foot of the altar (the altar was like a little table) in her hand; and (since that time) seven churches were burned down, in which this altar was, but it received no injury from the fire: Sed servata est per gratiam (favor) Brigidae. Dicunt alii, that this Church, to which Bishop Mel had gone, is in Feratullach. Ita ut alii putant.” (Fartullagh is near Bri Ele). – Liber Maculatus, Leabhar Breac, Fol. 31.

Colgan was ashamed of this. Cogitosus has not a word about it, or if he has, Colgan has suppressed it. I don’t laugh at these stories, for I think they are very nice if they were well told.[1]

For more on the Saint Brigid story see the Noel Kissane Life in the online Dictionary of Irish Biography. Some extracts below

The Brigit story Brigit was the daughter of Dubthach son of Deimre, a nobleman or military leader. He was of the Uí Bressail (Rawl. B. 502, 126a 28), a sept of the Fothairt, a subject people located in the present Co. Offaly, but with branches elsewhere. Brigit’s mother was named Broicsech; she is presented in alternative accounts as Dubthach’s wife (Cogitosus) or slave. When Broicsech becomes pregnant by Dubthach, in the scenario where she is a slave he sells her to a poet but retains ownership of the unborn child. The poet later sells Broicsech to a druid (magus) in whose house Broicsech gives birth to Brigit, who is born with the status of a slave. The location is not stated; claims for Faughart, Co. Louth are based on late medieval tradition. The druid kindly allows Brigit to live with her father Dubthach whose house was seemingly located in the area east of Cruachan Breg Éile (Croghan Hill, Co. Offaly). She is particularly involved with dairying and looking after the cattle, activities commonly represented in her iconography. She is especially kind to the poor and performs various miracles on their behalf. Her father and brothers want her to marry a suitor, but she refuses as she is committed to a celibate life in the service of God. Her father eventually allows her to take the veil. The ceremony is performed, according to different accounts, by one or other of the bishops Mel (qv) (d. 487) or Mac-Caille (qv) (d. c.489), the location probably being in Mag Tulach (the present barony of Fartullagh, Co. Westmeath).

Brigit is said to have established a convent at Kildare, but the Lives are silent regarding the date and the circumstances. ….

The hagiography of St Brigit is typically Christian and it echoes the Old and New Testaments, the Apocrypha and the early Fathers. It presents her as wise, humane, charitable to a fault, and concerned with the welfare of the common people. She is in constant communion with the Lord and is a prolific worker of miracles, which are almost invariably attributed to divine intervention and often have precedents in the New Testament. Many of the miracles and other aspects of the Lives, however, seem to reflect pagan religion or superstition; for example, the story of Brigit’s origin features a poet and a druid, both from classes with important functions in pre-Christian society; her suitor is the fictional poet Dubthach (qv) of the moccu Lugair, who is represented in seventh-century literature as a pagan who converts to Christianity; the only milk she can tolerate as a child is that of a white red-eared cow; and she resolves an unwanted pregnancy as if by magic. A notable feature of the Lives is a preoccupation with fire and light: a column of light rises from Brigit’s head; she hangs her cloak on a sunbeam to dry; the house in which she is asleep catches fire but remains intact. .

Folklore Echoes of pre-Christian religion and superstition are also intrinsic features of the folklore associated with St Brigit. Her feast-day (Lá Fhéile Bríde) on 1 February coincides with the pagan festival of Imbolc, one of the four quarter days of the pagan year, which marked the beginning of spring, lambing, and lactation in cattle. The feast of a saint was normally celebrated on the anniversary of the death, but there is no evidence that Brigit died on 1 February. Cogitosus states that she did, but the context suggests that his only evidence was her feast-day. In any case, the celebration of St Brigit’s feast-day retained various features of the pagan festival, including probably the straw or rush crosses, believed to bring luck to the home and the byre, and the strips of cloth representing Brat Bhríde (St Brigit’s mantle) which were claimed to protect virginity, cure barrenness, and relieve women in labour. The ceremonial often included visits to Brigit’s wells, some of which were thought to cure sterility. While much of the imagery relating to Imbolc was probably censored or Christianised at an early date, some of the folk customs associated with St Brigit’s Day retained explicit references to sexuality and fertility. Séamas Ó Catháin has identified parallels in the international folklore of northern Europe, especially that of Scandinavia, which suggests that the cult of the goddess was widespread and tenacious.

See also the Dictionary of Irish Saints by Pádraig Ó Riain below from the 2011 edition:

[1] See the Michael Herrity edition, pp 188–9.