There are many people of note from Clara, but two particularly can be seen as associated with the period of Partition; David Beers Quinn and Vivian Mercier. Despite the ongoing War of Independence, the British government passed the Government of Ireland Act in December 1920, providing for the setting up of two parliaments in Ireland. The 3rd May 1921 marked the formation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, so partitioning the island of Ireland. Vivian Mercier and David Beers Quinn had just reached their 2nd and 12th birthdays respectively. Although born a decade apart, in terms of Protestant identity, they represent different socio-economic backgrounds, illuminating what it was to be Protestant and Irish in the South of Ireland.

David Beers Quinn’s father, also named David, was a member of the Church of Ireland from Tyrone, He was employed as a gardener at the Goodbody house, Inchmore. His mother, Albertina Devine was also a member of the Church of Ireland from Cork with English parentage. Mercier’s father was from a Methodist family of Huguenot origin and his mother from a Church of Ireland clerical background from Monaghan. They lived in Cork Hill, Clara. The Mercier family, like the Goodbody family, were millers. Mercier’s father was born in Durrow, near Abbeyleix, Laois and was employed as a commercial clerk in jute manufacture at the Goodbody mills.

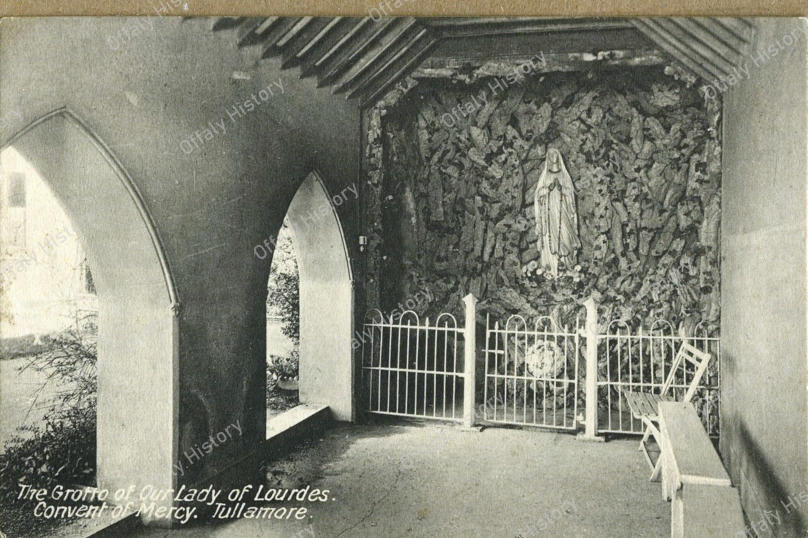

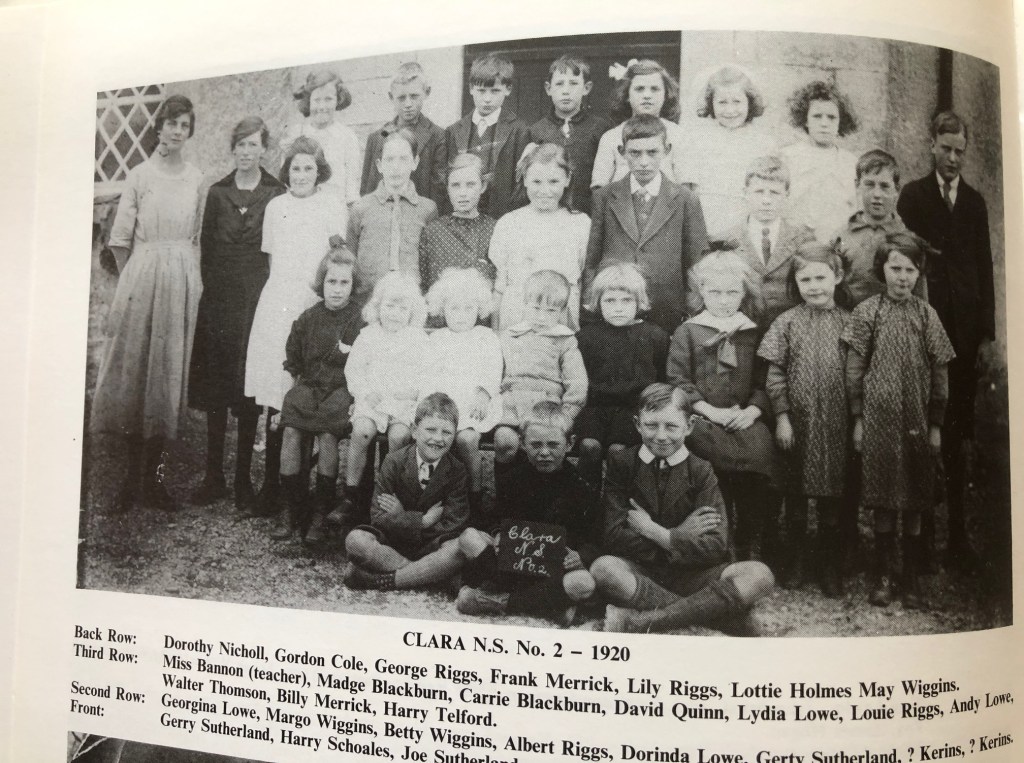

The partition of Ireland affected the education of Quinn and later Mercier. Quinn and Mercier attended Protestant National Schools, Quinn attending Clara No 2 Protestant school and Mercier, Abbeyleix South National School. Why Mercier attended school in Abbeyleix is unknown as the Clara National School was still under the tutelage of Miss Bannon who taught Quinn. However, it is known that Mercier corresponded regularly with Mrs Thompson, a later teacher at the school in Clara. Possibly the Mercier family had moved out of Clara due to unrest to the comparative safety of his father’s family home in Abbeyleix, approximately 60km south.

Quinn’s parents came to realise that their son was gifted. Finding good Protestant Irish education for a child from a working-class family was almost impossible if they stayed in rural Southern Ireland. The family moved to Belfast in 1922 where his father gained employment and in 1923 Quinn was able to attend the prestigious Royal Belfast Academical Institution. He continued his studies as an undergraduate at Queen’s University, Belfast between 1927 and 1931.

Mercier similarly left the South for Northern Ireland for his secondary education, attending the Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, one of the Public Schools founded by Royal Charter in 1608 by James I. Samuel Beckett (1906 –1989) was a former pupil. Critique of Beckett’s writing, particularly ‘Waiting for Godot’ was to shape much of Mercier’s career. Mercier and Beckett shared an affluent background and Huguenot descent in common.

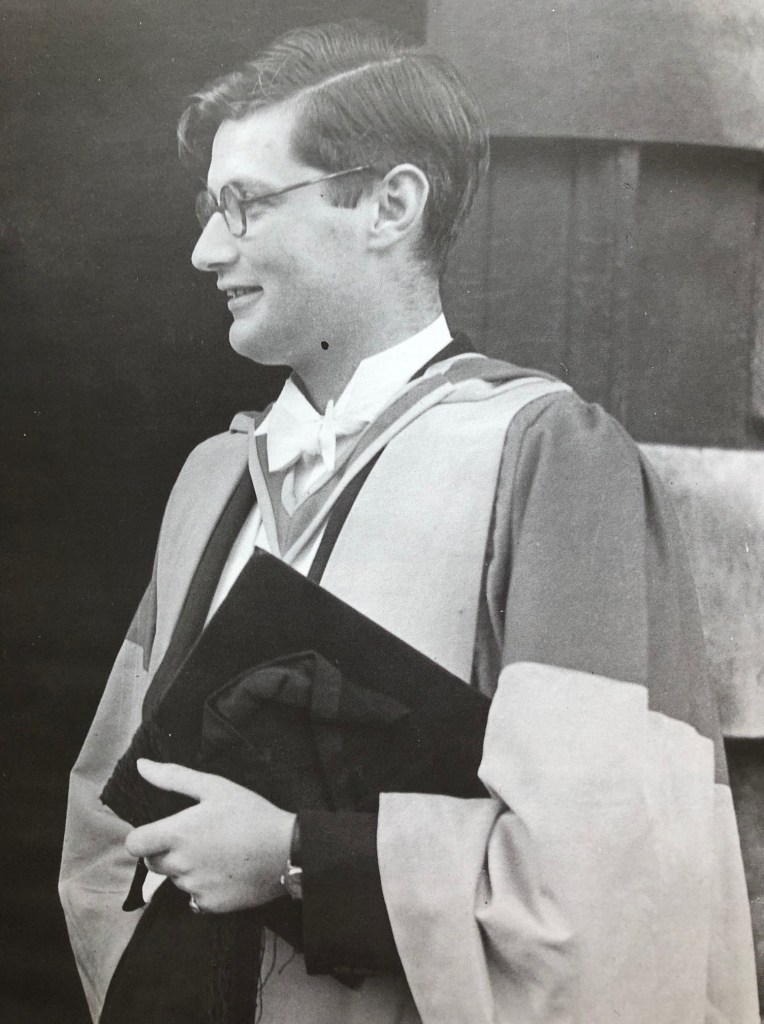

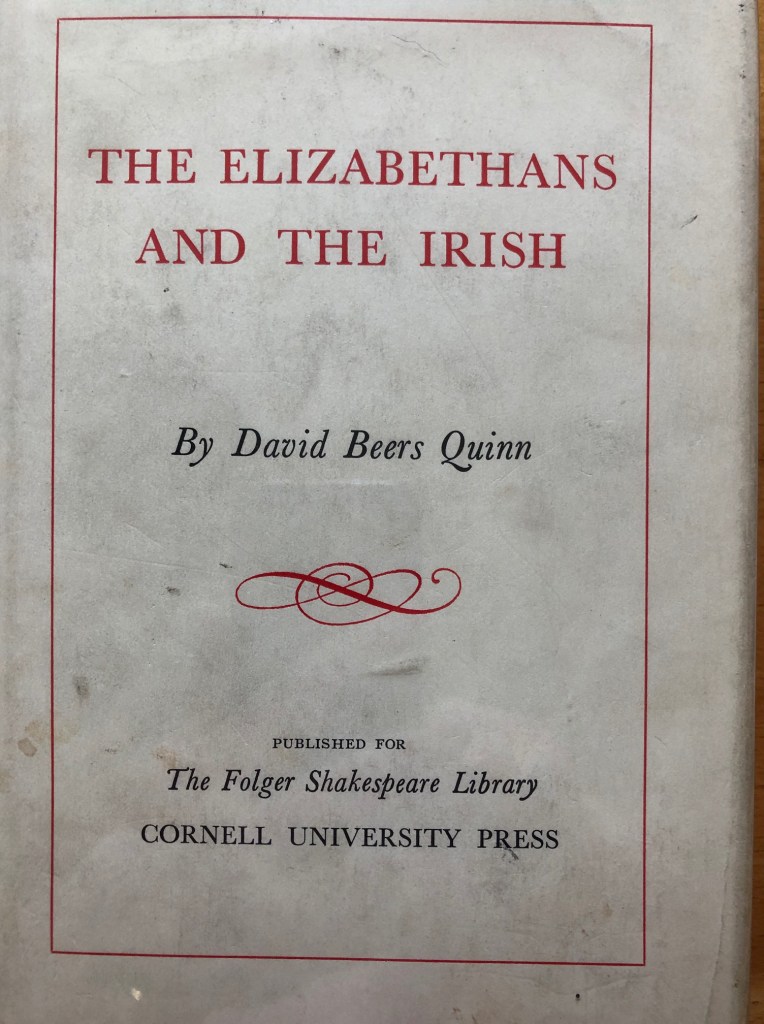

Quinn attended Queen’s College, Belfast (QCB) from 1927 to 1931 and then went to London University for his Masters’ Degree which he was awarded in 1934. There followed an academic career starting at Southampton (1934–9) and QUB (1939–44). After wartime secondment to the BBC European Service in 1943, Quinn moved to University College, Swansea the following year where he remained until 1957 when he moved to Liverpool university until 1976. Between 1976-1978 and 1980-1982 he was Senior Visiting Professor at St Mary’s College of Maryland. Alongside his academic teaching career, he wrote extensively on the voyages of discovery and colonisation of America. Many of his publications appeared as volumes of the Hakluyt Society. However, he continued to engage with Irish history writing The Elizabethans and the Irish (1966). Quinn also contributed substantially to both the second and third volumes of the New History of Ireland series (1987, 1976). However, his enduring influence on Irish history has been to link England’s involvement in Ireland with concurrent adventures in the Atlantic. Quinn married Alison Robertson whom he met whilst at Southampton in 1937. They were both politically active in radical politics. Alison worked with him particularly after their children grew up. She moved beyond indexing his work to becoming co-author and co-editor of several of his later publications.

Mercier attended Trinity College, Dublin between 1936 and 1939. In 1940 he married American, Lucy Glazebrook. Whilst studying for his PhD, he worked as a journalist for the Church of Ireland Gazette and contributed to the Bell, a magazine of literature and taught at Rosse College. Mercier pursued an academic career at Bennington College, Vermont City (1947–8) before moving to City College, New York, where he taught English 1948–65. He married Gina di Fonzi in 1950. He became known as an academic who enjoyed teaching. He co-edited, the anthology A thousand years of Irish prose (1952), which became a standard teaching resource. He also compiled Great Irish short stories (1964). During regular visits to Dublin in the 1950s, Mercier studied Irish with Trinity and UCD academics. These studies gave rise to The Irish comic tradition (1962), dedicated to Gina, which broke new ground by combining Irish-language and Anglo-Irish material in support of its central thesis that comedy preceded tragedy in Irish literature and that it was possible to trace a degree of continuity between work in both languages, paying particular attention to Swift and Beckett. Although initially receiving a hostile response, the book is now generally regarded as a key text in the development of Irish studies. In 1965, due to Gina’s declining health, Mercier moved to the University of Colorado as professor of English and comparative literature. Gina died in 1971. In 1972 Mercier was visiting lecturer at the commemoration by the American University of Beirut of the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Ulysses. Mercier married the Irish author, Eilis Dillon in 1974 and took up his last academic position as professor of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara. During these years Mercier and Dillon moved between California, Italy, and Dublin. Mercier retired in 1987 and he and Dillon moved permanently to Ireland. Here he reviewed books, contributed to literary journals and was a popular speaker at summer schools. He was writing a summative two-volume study of Modern Irish Literature when he died and his wife edited it and had it published in 1994.

Quinn’s obituary in the Irish Times at the time of his death in April 2002 suggests his initial interest in the history of colonisation may have derived from his childhood years. He came from a Church of Ireland ‘colony’ within a ‘colony’ of the Quaker Goodbody family set inside a predominantly Catholic town. In 1998 Quinn wrote an affectionate account of his childhood years growing up there, explaining the relationships between different sectors of the community.

Mercier similarly was influenced by growing up in Clara, believing his experience of going to school ‘under the curious gaze of Catholic contemporaries whose world differed so widely from his own’ as separating him from the Protestant populations around Dublin who were confident in their own identity.

David Quinn died 19 March 2002, predeceased by his wife Alison who died in 1993. He was survived by his three children. Mercier died whilst on a visit to London on 3 November 1989. He was buried with his parents in Clara after an ecumenical funeral service at St Patrick’s cathedral, Dublin. He was survived by his wife and three children. Quinn and Mercier had diverse careers but it would seem that growing up as Protestants in Clara at a time of when religious communities were divided, influenced the work of them both. Their legacy to Irish scholarship is significant.

Sylvia Turner, May 2021 with thanks to James Gibbons for additional material

Bibliography

N. Canny and K. O. Kupperman, ‘The scholarship and legacy of David Beers Quinn, 1909–2002’, The William and Mary Quarterly, lx (2003), 843–60; ODNB

Irish Times ‘ Irish historian who investigated exploits of British explorers’available @ https://www.irishtimes.com/news/irish-historian-who-investigated-exploits-of-british-explorers-1.1085040

D. Kiberd, introduction to Vivian Mercier, Modern Irish literature: sources and founders (1994)

D. B. Quinn, ‘Clara: a midland industrial town, 1900–1923’, Offaly: history and society, ed. Timothy P. O’Neill and William Nolan (1998)

A. Roche, ‘Vivian Mercier 1919–1989’, Irish Literary Supplement, spring 1990, p. 3

The Guardian David Quinn: Historian who defined our role in the discovery of America available @ https://www.theguardian.com/news/2002/apr/06/guardianobituaries.highereducation