The Christian Brothers have enjoyed a mixed press in Irish history. Earlier generations tended to ‘canonise’ the order, founded by Blessed Edmund Ignatius Rice, while in later years the tendency has been to ‘demonise’ it. Much of the criticism has, of course, related to issues around the alleged sexual abuse of boys attending residential institutions such as Letterfrack and Artane, while the order has also been accused of taking an excessively nationalist line. Getting a balanced picture of its contribution is not easy, but there is no denying the success achieved by many of its past pupils and the hurt caused to others.

In Tullamore, the order first came in 1862 and after withdrawing for some years due to a dispute with the parish priest over accommodation, returned in 1912, locating at St Columba’s Classical School, a building neighbouring the Parochial House. The building later became the De Montfort Hall, a parish building, and later an apartment block.

By the time I was a pupil of the old primary school in 1968-73, and the secondary in 1973-78, the Brothers were located at High Street, in a prefabricated structure built by Kenny’s Bantile in 1960. An extension was built in the 1980s but it, along with the bulk of the prefabricated structure, was demolished in 2011 to make way for the present school building.

In my Leaving Cert. year, there were no fewer than six Christian Brothers on the staff of Coláiste Choilm, of whom four – Brothers Murphy, Giffney, Rossiter and Brennan – are now deceased. The decline in vocations to the order gradually led to withdrawal from many schools, and in 1999, the order announced it was pulling out of Tullamore. Unlike other towns, like Portlaoise and Mullingar, where the Brothers retained trusteeship of schools even when none were left on the staff, they left Coláiste Choilm lock, stock and barrel, handing trusteeship over to the diocese of Meath, as had happened to their schools in Trim and Drogheda.

The last Christian Brother principal was Brother Noel Duffy, a native of Derry. He was replaced by Colin Roddy, followed by the current principal, Tadhg O’Sullivan.

By that time, the Brothers had left the old monastery in High Street, following a fire in 1987. The building is now the home of solicitor Donal Farrelly and Anne Farrelly. The order acquired a property in Clonminch Road, later sold to the Sisters of Charity of Jesus and Mary.

The name Coláiste Choilm, of course, reflects the connection with St Colmcille, founder of the famous monastery in Durrow in the sixth century. The Colmcille connection is also reflected in the fact that the old monastery in Clonminch was called Iona, in tribute to the saint’s foundation in Scotland.

A further connection was that for many years the order’s burial plot was in Durrow, in the grounds of St Colmcille’s Church. However, in the 1980s the Brothers acquired a plot in Clonminch Cemetery, where Brother George Giffney was buried in 1984, Brother James Brennan in 1986 and Brother Eoin Rossiter in 1995. Brother Patrick Murphy, the headmaster in my day, was transferred to missions in Zambia in 1978, the year I did my Leaving. He died there in 2006 and is buried in Zambia.

Overall, my memories of the Brothers are positive ones, though I am well aware that others have different memories. It has to be said that what happened in residential institutions, as highlighted in the Ryan Report, differed in many respects from day schools, where the boys were going home to their parents every evening. Corporal punishment was not something confined to Christian Brothers’ schools, and was a characteristic of many boys’ schools in that era. The debate on its value or otherwise is an ongoing one.

In general, the Brothers did not come across as being biased against other religious traditions. I recall one occasion when Brother Giffney was ahead of his time and got us to look up encyclopaedias to do research on different religions. He would ask one of us to set out to convert the class to Islam, another to Buddhism, etc. He would not have imagined the day would come when the school would have pupils of many faiths.

I vividly remember my last day in First Year and Brother Giffney said to us ‘Well, lads, the holidays are here and I’ve no doubt you’ll be meeting a lot of girls. There’s no harm in giving a girl a peck on the cheek but my advice would be not to do anything you wouldn’t want your parents to know about.’ It might not seem very radical by today’s standards, but I reckon it was very enlightened and forward-looking for its time.

While Brother Monaghan, as one would expect from a Banbridge man of his generation, had strong republican views, I can recall him telling us to always show respect for Tullamore’s then Church of Ireland Rector, Canon AT Waterstone ‘as he’s a man of God’ and made similar comments about the late Rev William Cullen, then the local Presbyterian minister. He also told us that if we ever met a rabbi, we should show respect to him as a man of God.

Many years after I left school, I recall covering the presentation to it of an aerial photo of the Blasket Islands by a past pupil who distinguished himself in the search and rescue services off the Irish coast. David Courtney, himself an active member of the Church of Ireland, spoke on that occasion of Brother Rossiter as a great teacher who instilled a love of Irish in him. David was himself a skilled athlete whose javelin coach was none other than Brother Murray, who attended a Holy Communion Service to mark his commissioning as an officer in the defence forces.

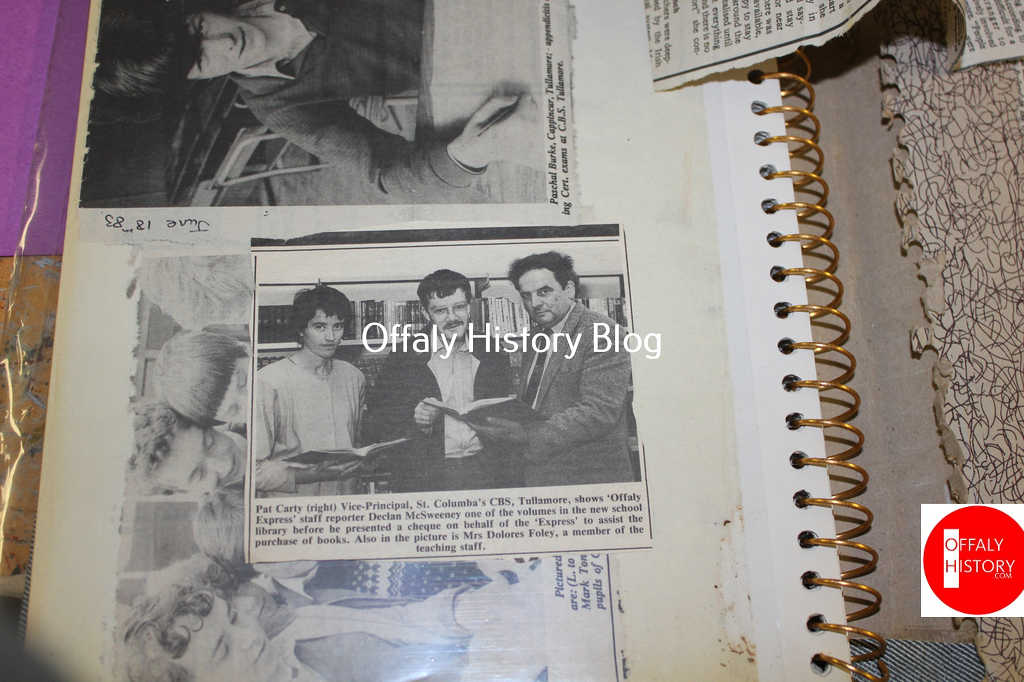

As far as the lay staff were concerned, several of the old teachers are now deceased – Séamus O’Dea, the deputy principal, Pat Carty, took over from him after retirement, Anne Ryan, Louise Carragher, Mary Glennon, John Friend-Pereira and John Cahill.

Pat Carty, who came to Tullamore in 1959, died in 2001 without living to see his retirement. After leaving the school, I frequently dealt with him while with Offaly Express, and always found him most helpful. He was a man who conveyed a deep sense of appreciation of literature, whether it be the plays of Shakespeare or Shaw, the novels of Dickens or the poetry of Wordsworth.

I can remember, with amusement, an occasion when he led us in the reading of Shaw’s “Heartbreak House”, with participation from the lads, in a very hilarious manner. He brought the sonnets of Shakespeare and the poetry of Kavanagh and Hopkins to life for his students.

It is good that awards are presented yearly in memory of him and of Mrs Ryan, alongside the Kearney and Wynter Awards. The Kearney Awards recognise top students in the Junior and Leaving Certs, while the Wynter Award recognises success in Woodwork. It honours my classmate Frank Wynter, a skilled carpenter who died in a road accident in 1986, within weeks of arriving in New Zealand. He had migrated there for work after completing a contract with John Flanagan and Sons involving the restoration of the Church of the Assumption. The Carty Award recognises success in English and the Anne Ryan Award that in Mathematics.

John Friend-Pereira, who died in 2008, taught me Science for some time in my Second Year in secondary school. In his day, he was a unique figure in the school and possibly in Irish schools, where an immigrant was a rare specimen in teaching. Originally from Calcutta, he had moved with his family to England in his teens and later to Ireland. In many ways, one could argue that having a teacher from a far land was itself a practical lesson in welcoming migrants, who were extremely unusual in the Tullamore of the 1970s – in those days, Italians running chippers and a few foreign doctors constituted the bulk of the immigrant population.

The elder statesman in the school was, of course, Geography teacher Seamus O’Dea. Other senior teachers included Sean Breathnach (though I was never a pupil of his) and Greg Cusack. A local man from the Ballinamere area, he was, in fact, unique among the staff of the time in being a native of the general Tullamore area, though he was not a past pupil, having been educated at St Finian’s, Mullingar.

John Cahill (nicknamed ‘Tiny’ due to his immense height) was the senior History master and is remembered in Tullamore for his work in promoting rugby. The Ballinasloe man had to walk carefully, as the Brothers were, of course, strong GAA supporters and the ban on ‘foreign’ games had only been removed from the GAA’s rules in 1971. However, significant numbers of the boys turned up on Saturdays at Spollanstown for training sessions with himself and fellow rugby enthusiasts Jim Mollaghan and Dinny Magner, both of them teachers in what was then Tullamore Vocational School, now Tullamore College.

One thing I recall vividly about John Cahill was an exercise he gave us, asking us to write out the names of ten Protestant denominations, so that we would not think in terms of ‘Catholic and Protestant’. It was a valuable exercise, as too many Irish Catholics have no idea of the difference between the Church of Ireland and Presbyterians, never mind the Seventh Day Adventists or the Elim Pentecostalists!

John Cahill left Tullamore to teach in Zambia, before returning to Ireland to take up a post in Dublin. His very confident demeanour was complemented by the mild-mannered Leo Minnock, who taught me English in First Year, Christian Doctrine in Second Year and Economics in the Leaving Cert. classes. I always found him very gentle and helpful.

Murty Davoren was my Irish teacher for five years, also teaching me Geography and Civics in First Year and History in Second and Third Years. The Moycullen native was a brilliant man who fostered a love for the language.

On one occasion, when two members of Tullamore Musical Society (Brian Hughes and the late Paddy Norton) visited the school to recruit members, they arrived during Irish class. Paddy sought to encourage us by saying that there were ‘a lot of attractive girls’ in the society.

Ron Meade was, of course, my Maths teacher for most of my schooldays, while Maura Adams introduced me to the French language.

The school chaplain in my schooldays was the late Father Michael Lynn, and we looked forward to his weekly visits to the school.

.

My memories of the staff are extremely positive and I feel conscious today, in many and varied respects, of what I owe to them. I realise my own memories are not always the same as those of other old schoolmates.

In later years, I was a regular visitor to the school during my 18 years with Offaly Express, covering many and varied events there, and I was glad of the opportunity to publicise them.

One major change that struck me, compared to my own schooldays, was that the school had become much more involved in the wider community, getting the boys involved in social action, whether by holding parties for pensioners or helping primary school children with learning disabilities. In this way, they were true to the vision of Blessed Edmund Ignatius Rice.