During the twentieth century a tradition arose of a Christmas bird, usually a turkey, being sent from Ireland to extended members of the family who had emigrated to the Britain. They arrived in a canvas bag packed in straw. The Second World War disrupted the tradition. It did not resume immediately after the War as the British Government thought that birds would be traded on the black market in contravention of food rationing as explained by the New Ross Standard 22nd October 22nd 1948.

However, it seemed there was a change of heart by the British Government by the end of 1948. Increasing numbers of emigrants were returning home to Ireland for Christmas by air rather than sea. This situation presented a problem to Aer Lingus. There were more passengers returning from Ireland than those leaving. A financial means of correcting this imbalance was needed. The solution was found by transporting ‘gift turkeys’ by air. They began offering a service by which turkeys sent by Irish families were flown to Britain during the week before Christmas via special Aer Lingus cargo flights. A notice in the Irish Independent of 24th November 1948 explains how the delivery was organised. Such deliveries were met with great excitement in Britain.

I remember one year in the 1950s that my uncle, a farmer, sent us a brace of pheasants. My mother was squeamish about plucking and gutting birds, so she took them to the local butcher to prepare and felt obliged to give the butcher one as payment. However, one pheasant yields at most 500 grams of meat and even as a family of three, there was just enough for one meal.

The ‘gift turkey’ scheme by air can be seen to have continued for a number of years as illustrated in The Wicklow People of 17th December 1960.

Another regular feature of the Christmas post from Ireland was the large tin of Jacobs assorted biscuits from my grandmother. Even though postage from Ireland was relatively cheap, it must have overshadowed the cost of the biscuits. I remember having to carefully unwrap the parcel of brown paper and string so it could be re-used, before being allowed a biscuit. My grandmother also sent my father a copy of the most recent Irish Times by newspaper postage rate. just wrapped in the middle with brown paper with the address.

It was at the end of the 1960s that Aer Lingus introduced off – peak fares. By then my grandmother was living with one daughter in Malahide near Dublin Airport and two other daughters, my mother and aunt, were living near London Heathrow Airport. The Belfast Chronicle of 18th December 1959 explains the new services.

In December 1961 my grandmother boarded a plane for the first time just after her 80th birthday as if she were boarding a bus. This time her presents were in her luggage, the tin of biscuits being replace by packets of Kimberly biscuits. She took to the experience of air travel as calmly as she took all the experiences in her life.

Today, transport between Ireland and Britain by sea and air is cheap and there are so many means of communication beyond the post. Goods once thought ‘Irish’ can be bought in supermarkets or online. It is hard to explain these memories of the Christmases of my childhood to my granddaughter as they must seem to come from another world to her. However, I can still evoke those excited feelings of these ‘Irish’ Christmases which to me were exotic but to my mother just represented the comfort of home.

Sylvia Turner December 2023

Look it up in Fowler or Freeman

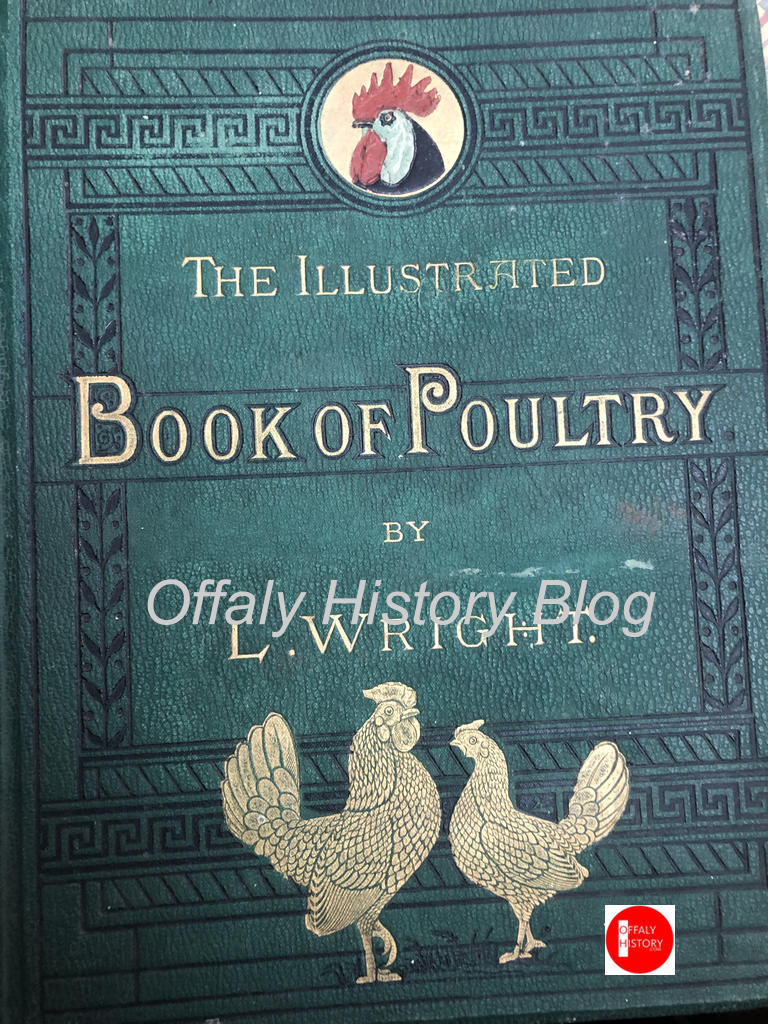

The blog editor adds that he looked up, not Fowler ( Modern English Usage) for illustrations of turkeys, but Wright’s, Illustrated Book of Poultry (1880), and secured a picture of the Wild American Turkey Cock of North America. Reference was made in this handsome volume to the Norfolk and Cambridge breeds and the ‘recently introduced’ [writing in 1880] ‘bronzed turkey’ of North America. He will have to consult with Ger Lawlor of Ballybryan, Co. Offaly – a well-known breeder for more information. In the meantime don’t let his meanderings spoil the turkey. What a a joy it must have been to be the recipient of a turkey from Ireland via Aer Lingus in the 1950s and 1960s.

Finally, the remarks regarding the export trade in poultry have a local resonance in the history of the Tullamore creamery and bacon factory.

Those surviving workers from the bacon factory/creamery in Tullamore may recall its extensive business in poultry including turkeys. The geographer, T.W. Freeman, writing 75 years ago (1947-8) noted:

The Midlands Co-Operative Society began its career as a creamery in 1928, and was at first intended to absorb the milk supplies of the neighbourhood for butter-making, but as these were never sufficiently great the trade in eggs and poultry became more important. Like the two private firms mentioned above [Williams’s and Egan’s], the Co-Operative Society buys and sells over a wide area, which includes the two counties of Leix and Offaly, the whole of Co. Galway, and parts of Tipperary, Roscommon, and Meath . Altogether the Society handles some 30,000 cases of thirty dozen eggs, of which three-quarters are exported to Britain, and approximately 24,000 turkeys, 5,000 geese, and 18,000 hens per annum, mainly for export or the Dublin market. Butter is bought from other creameries, made into one-pound rolls, and sold. In 1945, a bacon factory was added; the pigs are bought in Co, Offaly, and the produce sold in much the same area as that covered by the eggs and poultry trade. The scarcity of pigs at present means that the factory is working below capacity. The Society also has a sawmill using local timber for making cases and firewood and runs retail shops in Tullamore town and at Clonaslee: in all, it employs 180 workers, with 80 extra in the Christmas turkey season, and 20 extra in the main egg season, from February to May: most of this labour is drawn from the towns

Our thanks to Sylvia Turner for this timely article and for her contributions in 2023 to our blog articles and to Offaly Heritage 12.