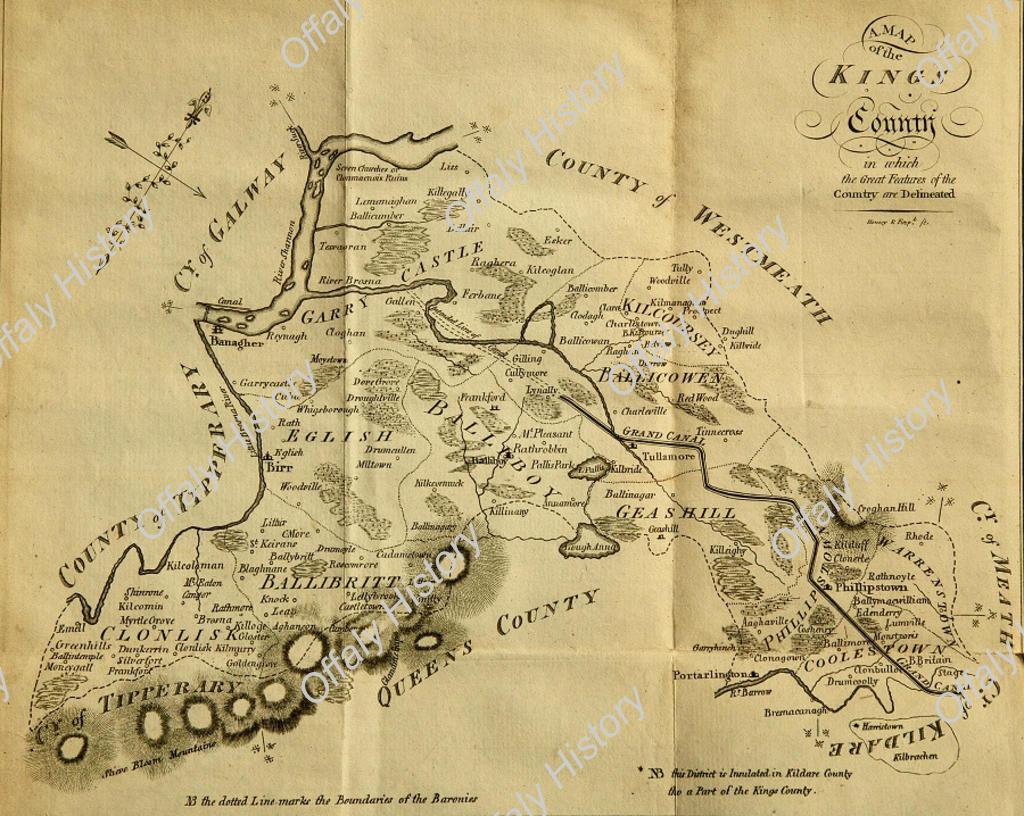

The Grand Canal reached Daingean in 1797. The changing landscape along the route of the new canal from Edenderry at its survey in 1800. Sir Charles Coote describes Philipstown /Daingean in No. 33 in the Grand Canal Offaly Series

The Grand Canal reached Daingean (Philipstown 1557-1920) in 1797 having been dug by upwards of 3,000 men from the access to the county at Cloncanon, Edenderry in about 1793. The next stage was making the line from Edenderry to Rhode, Toberdaly, Killeen bridge and into Daingean where the Molesworth bridge was built in 1796. After that it was on to Ballycommon, the 26th lock (Boland’s. ‘the Round House’) and the drop down all the time to Tullamore which was reached in 1798. The fall over the eight locks, from no 21 to no 28 at Clara bridge, Tullamore was about 73 ft. It was five years before the connection from the main line of canal at Cloncanon and Drumcooly was completed to Edenderry in 1802.

Coote in the survey published in 1801, dedicated to none other than General Vallancey who had surveyed the proposed line of the Grand Canal as far back as 1770 (see an earlier blog), was able to describe the scene close to the line of new canal of which so much was expected.

Clonbullock is a village between Edenderry and Rathangan, where is a new church, the houses small and very mean, there were two or three good dwellings here, burnt in the late rebellion [1798]: this was the only part of this country, where it actually broke out, and it is situate on the borders of Kildare county. In this barony the cottiers’ habitations are poor; the fuel is turf, which is plenty and cheap, though considerably increased in price since the Grand Canal has branched here, which skirts this and Warrenstown barony, for some distance. The food of the peasantry are potatoes and a good proportion of oat-meal, and they generally make their breakfast on stirabout; potatoes average eight shillings per barrel, of twenty-four stone; oat-meal ten to twelve shillings per cwt.; cottiers wages has been raised from five pence in winter, and six pence in summer, to eight pence and nine pence, and this hard season to one shilling per day: they pay forty shillings for a very good cabin and acre of garden, and thirty shillings for the grass of a cow: they have the advantage of rearing pigs and poultry, and every man, who has a cow, may keep a calf, free, on the pasture of his employer. The only distillery in the barony is at Edenderry; beer considerably increased in demand, but very bad. Several roads are in good repair, and others, with the bridges, are very bad; the idle effects of the rebellion still obvious. . . No schools nor charitable institutions in the barony, but at Edenderry, where the Rector of the parish is obliged to pay forty shillings annually to the master of a grammar school, which is a very mean establishment.

In the late season of severity, subscriptions were raised for the relief of the poor, whose wants were carefully supplied by the gentry. Shaw Cartland, Thomas Sennight, and _______ Lucas, Esqrs. are the only resident gentry, and have well circumstanced and very handsome demesnes. Mr. Cartland’s demesne is excellent land, and well planted with fine full-grown timber. Dublin bank notes only are current, little specie in circulation, and no manufacture inthis barony, but it has great advantages for one, as independent of the benefit of the Grand canal being so convenient, fuel is cheap and in plenty, water in abundance, and provisions to be had on very easy terms.

In the neighbourhood of Edenderry are three wind mills; and at Johnville, about four miles from Portarlington, is the only bolting mill in the barony; but there are several grift mills, which have neither good falls nor a command of water; the country around is very flat, and considerably damaged by the back water from these mills, which are of but inconsiderable powers, and supposed to do more mischief than they are worth, particularly so at Johnville.

At Lumville, which is Mr. Cartland’s seat, the country is woody and the plantations well thriven. Timber is very dear and had with difficulty. Near Edenderry is the small remains of an ancient grove; the natives of this country are more industrious than formerly; since the navigation extended here there has been no want of employment but for children; this, to be sure, is a grievance would be desirable to have remedied, and the introduction of manufacture only will correct it. The English language is almost entirely spoken. . . The Hill and Moat of Drumcooley were lately planted by Lord Downshire, but the trees are not preserved. A chain of moats extend through this country, and were strongly fortified; they all command toghers or bog passes, which were very numerous. Clonagown is rather a gay village, of triangular form, and clean appearance, situate forty miles from Dublin. Pigot Sandys, Esq. has a handsome demesne here, of the same name. Ballynure is a very mean village, in this district.

Great quantities of the finest ash are on the lands of Ballybrittain, the estate of Lord Trimblestown, where resided the late Joshua Inman, Esq. but the timber is now cutting down. Near to this is a stage, on the Tullamore branch of the grand canal, which skirts the barony. The resident gentry are, Henry Dames, and Thomas Wakely, Esqrs, and a part of Sir Duke Giffard’s estate branches here, on the borders of the county of Westmeath. In this barony are annually fattened near one thousand cows and bullocks, and several thousand sheep; a greater number of each kind are sent from hence than from Coolestown. There is no town here, and but the small village of Rhode, ’tis aptly situate for a thriving town, and on the estate of Thomas Wakely, Esq. but all the adjoining ground is let in perpetuity. Mr. Dames has some young plantations thriving vigorously, and well attended to; and at Rathmoyle, the seat of Mr. Berry, are also some young trees, fine full grown timber, and excellent hedge rows. Part of Castle Jordan parish, in the adjoining county of Westmeath, branches into this barony. The Yellow river is the only river here. I cannot learn why it is so called: its waters form but an inconsiderable stream.

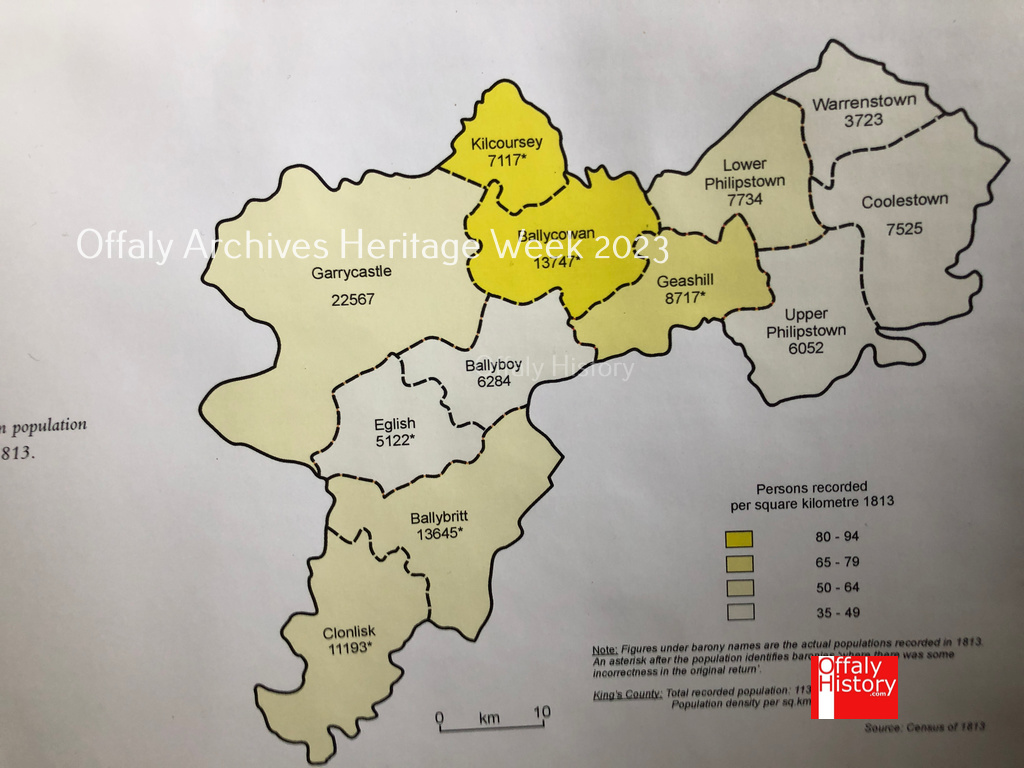

Philipstown – upper and lower baronies: the harsh winter of 1800-01

The mode of culture differs little throughout; the four-horse plough being almost solely used. The far greater proportion of the ground is under tillage, and every kind of grain sowed to good account: all the uplands are arable, and the moors and low-grounds are stocked with store cattle, which are here in numerous herds. They either break ground with potatoes sowed on the lay, of which they take two crops; next take two or three crops of oats, and then sallow for wheat or bere, but first spread with limestone-gravel before seed sowing; or, after paring the surface, they gravel, and sallow for wheat; next sow oats, then again sallow, and keep up this succession, and sow their bere and potatoes in low ground, which they always burn. They have not had any improved implements of husbandry, except the patent winnowing machine, which I have seen with a few gentry, on a small scale. Tullamore and Kilbeggan are the market towns for grain of the upper-half barony; Portarlington and Mountmelick those of the lower: Philipstown common to both, and has but a very sorry market, and little frequented. More opulent farmers send their corn to Dublin by the canal, which intersects this barony. They cultivate no green food for their cattle in winter; rape is only sowed for feed, and they fodder in the fields in cribs.

The labouring peasants often go from hence to look for work abroad, rather than take reasonable wages; this combination is steadily persisted in, though they are paid 9d. and 10d. per day through the year. Cottiers wages, 7d. per day in winter, and 8d. in summer; they have an acre of garden and house for 40s. annually, and pay 30s. for a cow’s grass; the keeping of a calf not charged till a year old, and every privilege of pigs and poultry allowed them: turbary is free, consequently they have no want of fuel. Food, mostly potatoes and oatmeal; and, where there is more than one labourer in family, they often afford bacon, and live well: few cottiers but have a cow. Average price of potatoes, 3d. per stone; oatmeal 11s. per cwt. Beer in great demand. The country being very boggy, occasions many bridges, which are very dangerous, seldom better than hurdles thrown across the stream, sodded and gravelled over. They are

systematically penurious in repairing these roads, which are in very indifferent order, and must in the winter season be in a very wretched state. There are no mines found here, nor is there any river of note, or navigation but the Grand canal. . . Education is in a low state, nothing better than the poor-schools for peasants children. There is no nursery for sale in this barony, nor manufacture; timber is had from Dublin by the canal, none being here for sale of any kind, but what is had from Killeigh woods. The women being rather industriously inclined, and well trained to spinning worsted, which they are obliged to send to market without the barony, argues much for the success of a woollen factory, if attempted here, for which there is every natural advantage; and, from the many grift-mills which appear, a good site could not be wanted. ‘Tis surprising, on this account, there are no bolting-mills in a country so prolific in corn, very little inferior to the best corn county in Ireland. There is here considerable quantity of moor [bog] which could be reclaimed at a small expence: they have excellent falls, and limestone is very abundant and convenient. English language generally spoken, and the Irish tongue evidently decreasing. . . . Thomas Magan, Esq. resides at his beautiful seat at Clonerle, [sic] which he rents from Mr. Doolan Medlicott; but this gentleman has a very considerable estate in the county of Westmeath. This demesne contains about 200 acres, which are elegantly enclosed and planted; the farm cultivated after the best improved methods, and here are the greatest variety of well-chosen implements of husbandry. This beautiful seat altogether highly delights the eye, and richly ornaments the surrounding country; it is situate two miles from Philipstown. The dead flat and level of this barony is agreeably relieved by Croghan Hill, which stands in majestic pre-eminence, and in this country forms a remarkable feature, beautifully clothed with verdure to its summit, from whence it commands a most extensive prospect; a large tract of it was formerly enclosed as demesne land for Lord Tullamore’s ancestry, whose estate it is; and at the foot of the hill are the ruins of Croghan church, which was a chapel of ease for that family [demolished about 80 years ago]. Its pasture is of a purgative quality, and the small breed of sheep, when sent thither, grow to a large size, and throw out considerable fleeces. Mr. [Arthur] Young, in his agricultural tour through this kingdom, speaks of Croghan Hill as producing twelve pounds to the fleece; .. The hill has been celebrated by Spencer in his Fairy Queen; on its summit is an ancient burial-place, and its boundaries divide this county and that of Westmeath.

This country is very thickly inhabited; Philipstown [until 1835] which is the county town, and the only one in the barony, has hitherto sent two members to parliament; it has till lately been in a wretched state, and was rapidly fallen to ruin: now there is but little to recommend it. This town was originally part of the Molesworth estate, and, through family connections, is now divided into three properties; the most considerable part of it is enjoyed by the Right Hon. Mr. Ponsonby. The new leases now given are encouraging, and several new houses are erecting [probably those in Molesworth Street and close to the canal]. The Grand canal passes at the northern end of the town, and, before this navigation, was complete to Tullamore, it was of very material service to this town, but now of inconsiderable advantage. A new county gaol is also erecting at the rere of the barracks, which are extensive, and command the town: it is almost entirely surrounded with bog. consequently fuel must be cheap and abundant; and provisions are in plenty, yet no manufacture of any kind is carried on. It had formerly a garrison, and the ruins of a lofty castle are situate on the brink of the river. This town is thirty-eight [Irish] miles distant from Dublin.

About the author of the first survey of King’s County, Sir Charles Coote

Linde Lunney wrote in the the DIB

‘Sir Charles Coote, (1765–1857), baronet and author, was the illegitimate son of Charles Coote (1738–1800), earl of Bellamont, and Rebecca Palmer. The earl, writes Linde Lunney had eleven other illegitimate children by four other women, had obtained a special remainder for his English baronetcy, and Charles Coote junior succeeded to the English title on his father’s death. His marriage to a Miss Richardson may have displeased his father; he inherited £1,000, but no share in the family’s estates. Sir Charles seems to have married secondly (November 1814) Caroline Elizabeth Whalley; they possibly had a son the following year. In 1800 he undertook on behalf of the (Royal) Dublin Society a tour through four counties of Ireland as one of a number of writers gathering information for a projected series of county surveys, and also corresponded with local landowners and industrialists. In 1801 the society published his General view of the agriculture and manufactures of the King’s County, and a similar survey of Queen’s Co.; in the same year appeared Statistical survey of the county of Monaghan with observations on the means of improvement; in 1802 a similarly titled study of Cavan, and in 1804 one of Armagh. This series of surveys was regarded by contemporaries as slightly disappointing, but Coote’s volumes are frequently cited by historians, and for some subjects provide unique evidence. He died 25 May 1857, and was succeeded by his son Charles (b. probably 1798). He should not be credited with creating the house and gardens at Ballyfin, a property owned by Sir Charles Henry Coote (1792–1864), 9th baronet (of a different family); nor should he be confused with the Charles Coote who published a number of well-known historical works in the early nineteenth century.’