Between 1849 and 1867 a nationwide network of almost thirty Model Schools was established by the Board of National Education. These schools were under the exclusive control of the Board and it was expected that attendance would be drawn from the various denominations to be found in the area of each school’s location. The primary aim of these institutions was to provide a regulated system of training for candidate teachers. Due to a growing reluctance on the part of the Roman Catholic hierarchy and clergy to be associated with these institutions where they had no input into management, the establishments were decidedly skewed towards Ulster. This became even more pronounced when a scheme for the establishment of those schools termed Minor Model Schools – as opposed to the more prestigious District Model Schools – was put in train. Of the seven such schools, only one – Parsonstown Minor Model School – was located outside of Ulster. As such it was an exotic.

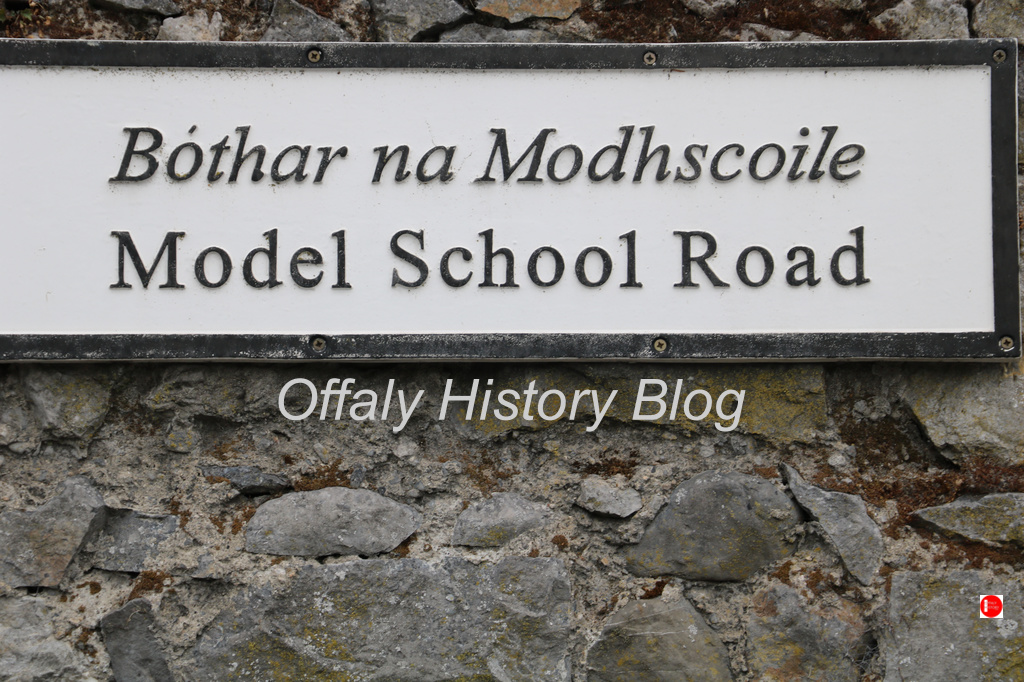

Out of deference to Roman Catholic sensibilities, the first site offered in Parsonstown was turned down, ‘owing to its proximity to the Convent School and Roman Catholic chapel’. The Board of National Education, having secured an alternative site from the Earl of Rosse, in proximity to his own residence, proceeded with the project. Very quickly Revd John Egan, the parish priest, declared his principled opposition, stating that no Roman Catholic clergyman could countenance support for such an institution among his flock where the spiritual leaders had no say in management. Furthermore, he warned the Commissioners that the venture would certainly fail. But despite his efforts, the influence of the titled Parsons family, with its support, both overt and practical for the project, ensured that, while Egan’s attitude would markedly limit the support for the school from the local Roman Catholic lay community, ultimately a minor model school would be established.

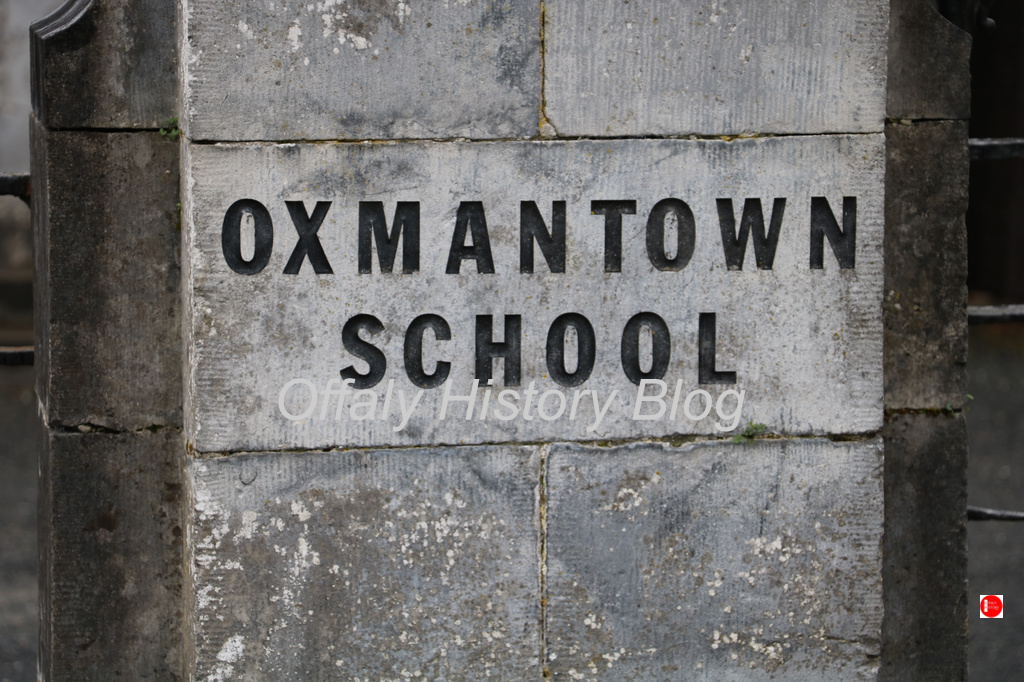

It was built at a cost of £2363, with a further £23 expended on furnishing. Cost of erection for the seven Minor Model Schools varied considerably. Ballymoney, at £1480 was the cheapest (Parsonstown was next cheapest) with Lurgan at £5923 costing the most.

As the opening of the school approached in October 1860, it became apparent that Fr Egan’s threat was not made lightly. Having failed to influence the Board, he appealed directly to his parishioners. The manner in which he sought to bring influence to bear on his captive audience was reported in lurid detail by the Morning News:

One of the curates, in the heat of his over zeal, stamped his feet on the altar, shook his clenched fist at the congregation, and dared them to attempt to send their children to the Model schools … Father Egan and his coadjutors … since Sunday last have been going to the houses of their parishioners and warning them of the consequences, should they dare to disobey the commands of the Church …

Notwithstanding these efforts, the readers were assured that the model schools would ultimately succeed. Initial indications were that the efforts of Fr Egan and his curates were successful. On opening 2 November 1860, there was an attendance of just fourteen. This, though, appears to have had little to do with the actions of the clergy, and was indicative more of a general tardiness to avail of the new school. Throughout 1861 the average daily attendance was 97.8. By the end of 1862 this had increased by a 40 per cent to 137.7. When broken down by denomination, the effect of the clerical becomes readily apparent. In a town where 78 per cent of the population was Roman Catholic, only 12 per cent of those enrolled were of that persuasion.

Some interesting detail is thrown on the situation in the Report of the Commissioners of National Education (1862). Head Inspector W. H. Newell, in a mostly upbeat report, stated that the progress of the school throughout the year was ‘altogether satisfactory’. He noted the increase in attendance, and was of the opinion that ‘the instruction of the classes was effectively and successfully carried on, and [that] every detail connected with the management of each department was duly attended to.’ He could not avoid, though, acknowledging the fact that the small number of Roman Catholics in attendance was disappointing ‘owing to the active and increasing opposition of the Roman Catholic clergy.’

On a decidedly more positive note, he reported that Lord and Lady Rosse ‘were pleased to authorize the award of prizes to the most deserving and distinguished pupils. The successful boys were Richard Heenan and John Barlow, who prizes in Physical Science, and in Geometry and Algebra, John Barlow and Richard Mathews. Three girls, all in the category ‘Best General Answering’ were rewarded for their efforts: Maud O’Brien, Eliza Murphy, and Eliza Ryall.

H.I. Newell also informed the Board that the schools were visited during the previous year ‘frequently by Lord and Lady Rosse and occasionally by other distinguished persons’, among whom he mentioned Dr Fitzgerald, Bishop of Killaloe and Mr W. Senior Nassau Senior ‘of London’. Lord Rosse was reported as stating that ‘the children in attendance are receiving a useful education, practical and enlightening, in a manner and to an extent equalled by few schools in the provincial towns of the Empire’. Nassau Senior (1790-1864) was an English lawyer but with an especial interest in economics, social conditions and popular elementary education. Widely travelled, he is probably best remembered in Ireland for his work Journals, Conversations and Essays Relating to Ireland. Of him, Newell wrote: ‘The favourable testimony of one so conversant with the condition of elementary Education in England is valuable.’ [Offaly history are planning blogs about Nassau Senior visits to Laois and Birr]

While, in general, Newell was pleased with the level of attendance – for Boys, Girls and Infants, in 1861 the average daily attendance was 97.8, increasing substantially to 137.7 in 1862 – he did express disappointment with the attendance in the Infant School. While there were 46.3 Infants on rolls in 1862, there was an average daily attendance of just 19.1. This he attributed to two factors: ‘the school was somewhat distant from parts of the town’ and (unspecified) ‘epidemics reduced the daily attendance.

Despite the efforts of the Roman Catholic clergy, over time there was a steady increase in the attendance of Roman Catholics, reaching a high of 47 per cent in 1867. Thereafter, it gradually slipped back to 26 per cent in 1874.

The Parsonstown situation was not typical. It was the principal residence of a powerful gentry family that took a keen interest in local affairs. As employers and benefactors, their influence was considerable. Pitted against this influence was the authority of the local Roman Catholic clergy. Under the circumstances, it was unlikely that there would be a clear victor in the short-term, with the Roman Catholic laity torn between two loyalties. In the struggle between clerical authority and secular patronage, it would seem that, in line with the general trend, when the former could provide alternative institutions, efficiently run, they would in time prevail.

Our thanks to Joseph Doyle for this article and to Offaly History for the pictures of the school building in 2023. For more reading see the book below and the files of the King’s County Chronicle. The original school registers are now in Offaly Archives. To view email archivist@offalyhistory.com.

In the field of Irish education during the nineteenth century, the most significant government initiative was the establishment of a system of national education, which succeeded in providing regulated elementary education for the masses. However, the government attempt to provide these locally managed schools with teachers trained through a nationwide network of model training schools, under its exclusive management, was fraught with difficulties. Lack of funds and the failure to establish the board of national education as a corporate entity delayed implementing this objective until 1846. Over the next twenty years the establishment of a network was influenced by several internal and external factors. Practical difficulties encountered by the board, particularly its inability to control costs, meant that progress was much slower than originally planned. Gathering Roman Catholic clerical opposition, focusing on the board’s failure to provide a management role for any but its own officers, eventually denied the model schools the support of many of the Roman Catholic laity. This skewed their final geographical distribution towards Ulster and the larger urban areas outside of that province. This work sets out to explore the background of the initiative. Tracing the spread of the network, it will evaluate the support for and the effectiveness of the training programme, and most importantly assess the impact of the growing Roman Catholic Church opposition to all aspects of the model school system. Ultimately, it calls into question not only the effectiveness of the preparatory training and indeed the commitment of candidate teachers, but its very raison d’etre.

Supported by the Department of Culture Communications and Sport as part of the Commemorations Series.