The recent decision of the Health Services Executive to allocate funding for the renewal of the windows, doors and walls of the chapel of the original Offaly County Hospital, Tullamore is a welcome and well-timed architectural conservation initiative.

Opened in 1964, the building, which is a Protected Structure of Regional Importance, is an interesting example of stylistic change in Irish church architecture in the mid-20th century.

Though its exterior has been compromised by surrounding buildings, the serene and elegant interior is still totally intact.

The County Hospital

The County Hospital was built in the late 1930s and opened in 1940. Today it is considered to rank along with Dublin Airport as one of the best examples of Irish Modernist design and was to be the launching pad for the extraordinary career of Michael Scott who went on to become the most influential architect of his generation.

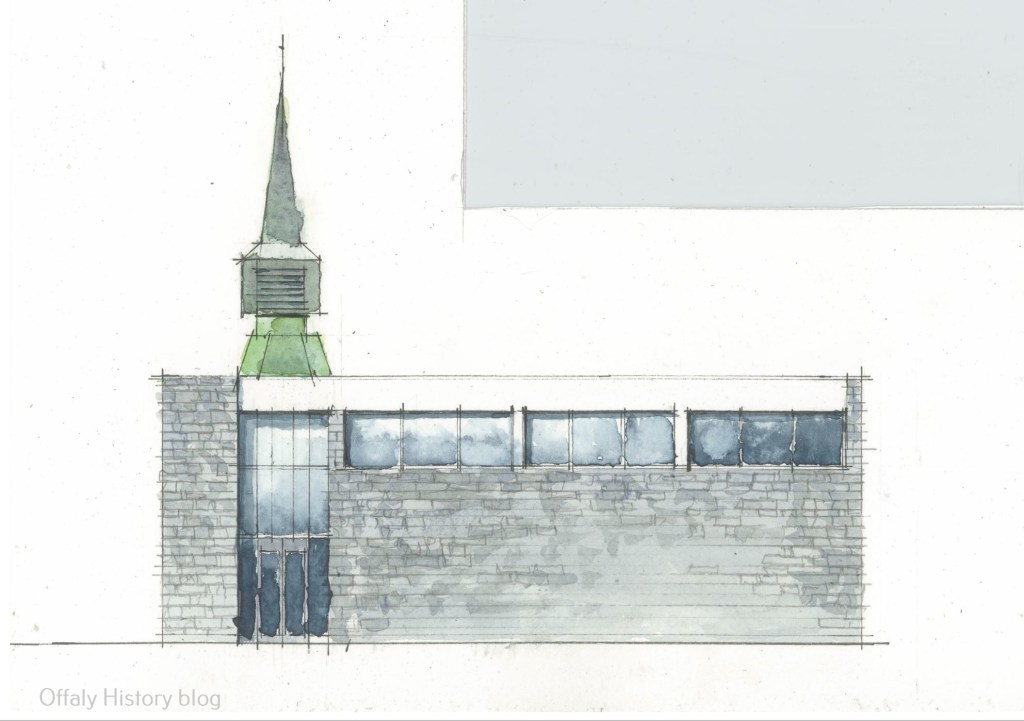

Its exterior displays a unique mixture of horizontally laid rugged local limestone contrasted with a vertical glazed staircase and a strong semi-circular central bay. Its light filled interiors set a new standard in hospital design.

The Chapel

By the 1950s demands on the County Hospital had grown and suitable accommodation was needed for the growing nursing staff together with a Catholic Chapel. A site was allocated to the east of the Hospital block.

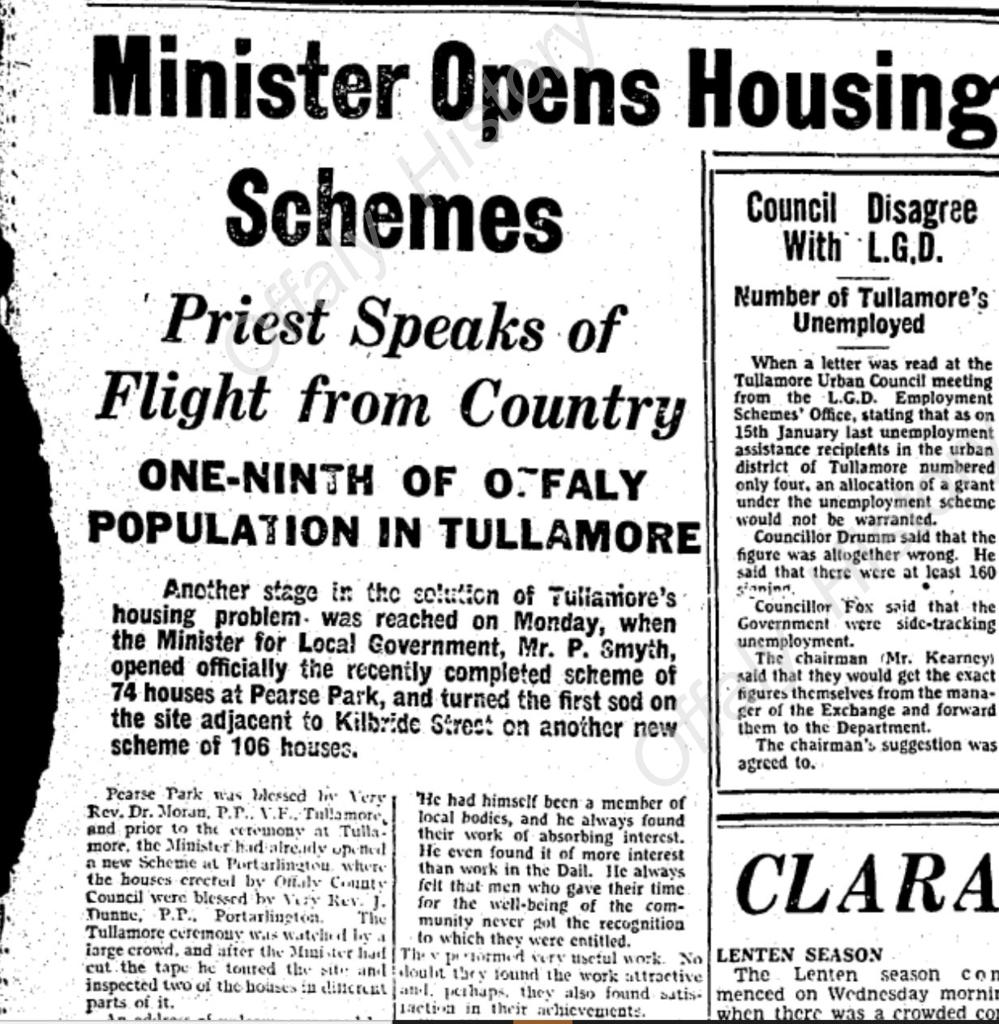

The commission was awarded to the architect Donald Tyndall who had a high local reputation having just completed the admirable Pearse Park and Marian Place housing schemes in Tullamore.

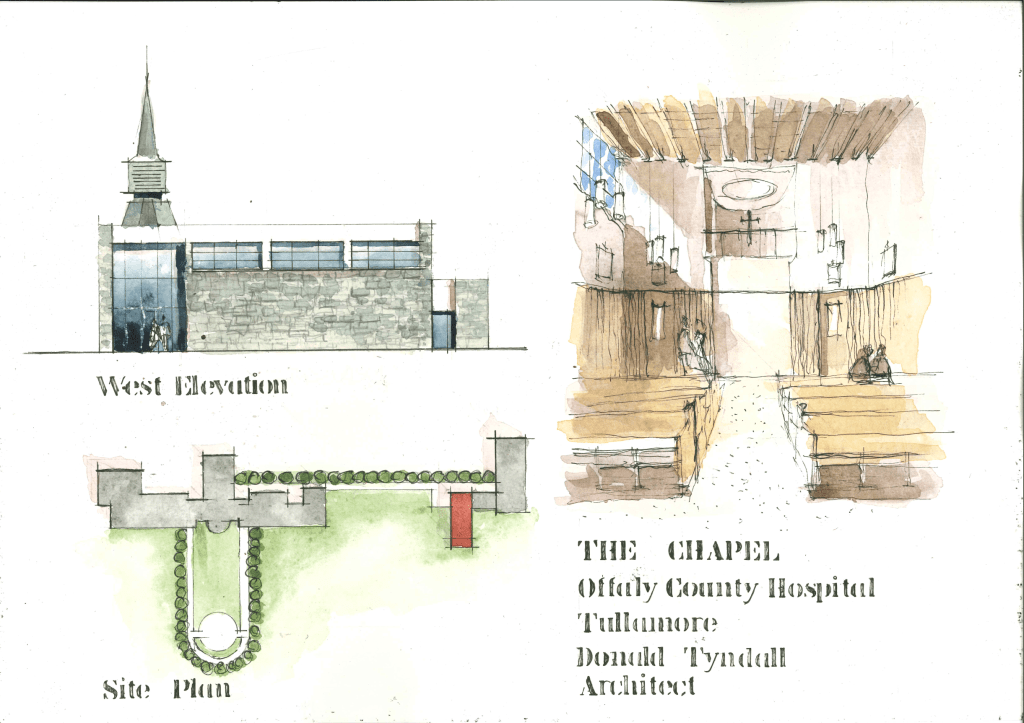

Tyndall provided a freestanding L-shaped block containing a two storey pitched roof nurses home of traditional design abutting a Chapel in a very different style with both linked to the Hospital by a pathway.

The Chapel is a simple but elegant flat roofed uninterrupted interior space with a top lit first floor choir gallery and an Oratory over an entrance foyer. A lower single-storey sacristy is attached to the southern end. The walls, floor and pews are finished in unadorned woods of differing colours and textures and this simple and unified treatment creates a wonderful calming effect. The lines of a rising sun etched on either side of the altar are the sole decoration. The proportions of the internal elements are based on the square which imparts a sense of solidity. Clerestorey lighting illuminates the interior on the western side with a full height stained glass window lighting the altar on the eastern side.

In particular the original lamps, which hang in groups of three, have been retained and provide a delightful example of 1960s interior decor.

The structure consists of concrete beams supported on columns while the exterior is finished in the same rusticated Ballyduff stone as the original Hospital. The overall external appearance is almost industrial in character, the only indication of its religious function being the elegant copper fleche atop a casing for a church bell.

It is possible to see some similarities with Scandinavian church architecture of the 1950s as opposed to 1930s Dutch Modernism which is the principal influence on the design of the Hospital..

In later years the transformation of the County Hospital into a Regional facility necessitated a massive programme of expansion which required the demolition of the Nurses Home. The Chapel was retained, though so surrounded by new buildings as to be almost invisible. Its wonderful interior, which is one of the finest in Tullamore, thankfully escaped.

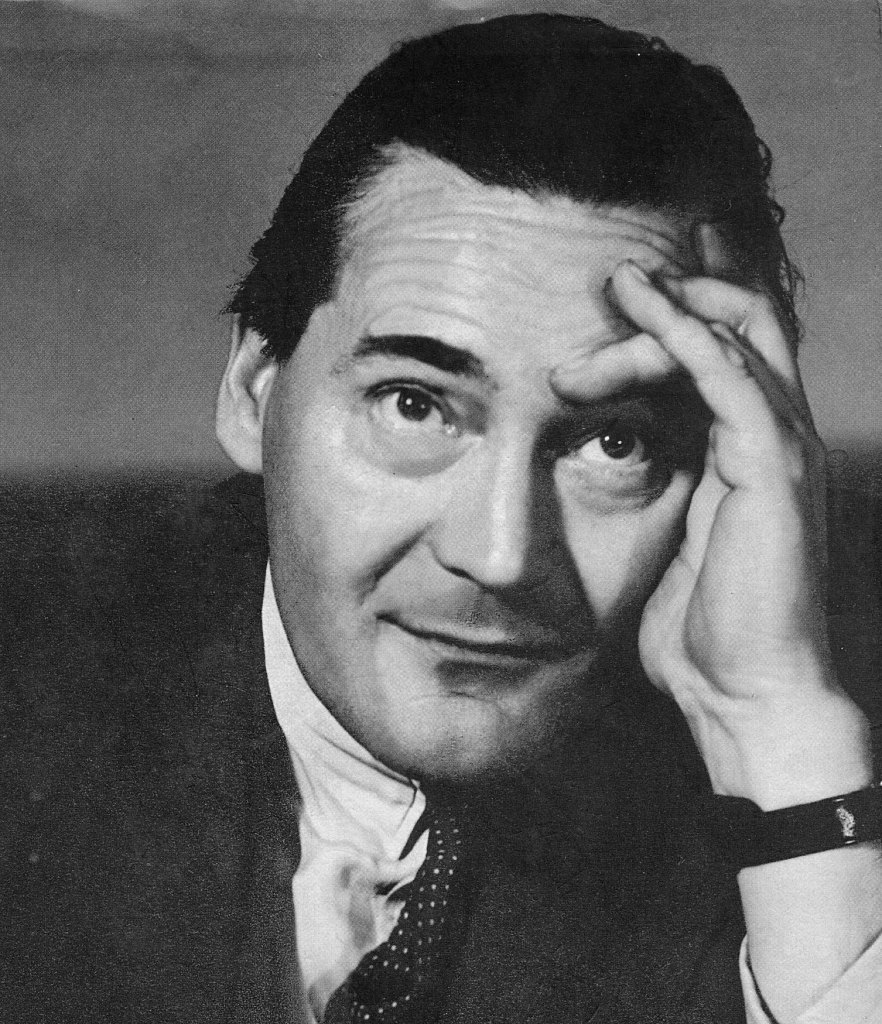

Donald Tyndall

Though his influence on the footprint and urban character of Tullamore through his housing schemes is significant, little is known of the architect Donald Tyndall.

The son of Joseph Patrick Tyndall, a Dublin solicitor, he studied architecture in London, qualifying in 1926 and working there until 1928 when he went to Shanghai, where he became involved in hospital design.

In 1933 he returned to Dublin and was appointed an assistant architect in the Corporation’s housing architect’s department. From 1937 until the early 1940s he worked in partnership with the engineer John Winter on a new county hospital for Cavan.

Tyndall’s career was interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served as an officer in the Royal Engineering Corps, attaining the rank of major. Returning to Ireland after the war he established his own practice in Dublin. Much of his work was for local authorities, and included hospitals and clinics in Co. Kerry.

In the late 1940s he was appointed to provide designs for the ambitious housing programme of Tullamore Urban District Council. The main project was the delivery of seventy-four houses in Pearse Park and one hundred and six houses in Marian Place. The names of the estates evoke the political and religious atmosphere of the period. They would be joined in 1965 by the sixty house Kearney Park dedicated to the popular local politician, Joe Kearney.

Together these three schemes represent a high point in local authority housing not just in Offaly, but in Ireland. By grouping the dwellings around clearly defined, generous and supervisable local greens a distinctive civic character was achieved.

Besides the Tullamore schemes, it is possible that Tyndall designed other schemes for Offaly County Council, but the only one which can be positively identified is St Cynoc’s Terrace in Ferbane

This twenty-six dwelling estate laid out in three blocks of six houses and two blocks of four houses around a fine rectangular green displays the same attractive well-mannered urban qualities of the Tullamore schemes.

Tyndall and the well-known Dublin architect Brian Hogan formed a partnership in 1960 and were joined by Richard Hurley (noted for his writings on church architecture of the time) in 1968 when the firm became known as Tyndall Hogan Hurley and went on to become one of the most successful architectural practices of that era.

Tyndall retired in 1968 but remained as a consultant until his death in 1975.

A Conjectural Influence

It is not impossible that Michael Scott was offered the commission to design these extensions to his original design, but by the 1960s he had moved away from the increasingly specialised area of hospital design and had been joined in the practice by Ronnie Tallon and Robin Walker. The new firm of Scott Tallon Walker was concentrating on large scale commercial, cultural and educational projects such as the RTE headquarters and the Abbey Theatre.

Nonetheless, in 1960 Scott was approached by his old friend the Parish Priest of Knockanure in County Kerry to design a Chapel of Ease for the village and accepted the challenge, while warning that the result would be an unapologetic modern design. The progress of this relatively modest project and the subsequent reaction of the parishioners makes for the most entertaining reading in Dorothy Walker’s wonderful book based on their casual conversations ‘Michael Scott Architect’.

The finished Chapel, which was designed by Ronnie Tallon, is a simple building with two end walls of glass and two walls solid, with clerestorey lighting above. Today it is regarded as probably the first building in Ireland to strictly conform in its design and setting to the Modernist principles of Mies Van der Rohe which would become the signature style of the practice.

In its structural clarity, concern for proportions, lack of adornment and visual simplicity the Tullamore Chapel shares the architectural values of the Knockanure Chapel.

In the small world of the architectural profession of 1960s Dublin, might it be possible that Tyndall was anxious for his new Chapel to harmonise with Scott’s Hospital and consulted with him and sought his approval and might Scott have shown him the Knockanure design which was being worked on at that time?

What an intriguing subject of study for an architectural historian!

Published by Offaly History with the support of the Department of Culture, Communication and Sport.