There is little doubt that contact by sailors from Norway had occurred over many years in the 8th and 9th centuries between the islands of northern Scotland, the east coast of England and with Ireland. Most of these sailors would have been fishermen or traders and would have acquired details of the Irish coastline, location of rivers and awareness of monastic sites. This intelligence was readily available when the Viking raiders came calling.

Tony Lucas in his paper on the plundering of Irish churches makes the point that of the 309 ecclesiastical sites that were plundered between 600 and 1163AD, the Irish themselves were responsible for 139 of these. Only 140 of these can be directly attributed to the Vikings and 19 raids are attributed to the Irish and Norse together. An entry in the Annals of Ulster for 755 records ‘The burning of Cluain Moccu Nóis on the twelfth of the Kalends of April’ by the Irish long before the arrival of any Viking.

In addition, Irish clerics took aim at nearby monasteries. We have two accounts where Clonmacnoise attacked its neighbours. Firstly, Birr was the subject of an attack according to the Annuals of Ulster for 760 ‘A battle between the communities of Cluain and Biror in Móin Coise Blae’, four years later the annal records that ‘The battle of Argaman between the community of Cluain Moccu Nóis and the community of Dermag (Durrow) in which fell Diarmait Dub son of Domnall and Diglach son of Dub Lis, and two hundred men of the community of Dermag’.

The defeat of the Vikings at the Battle of Clontarf did not remove the threat of plunder and destruction; the Annals of the Four Masters tell us that in 1098 ‘The oratory of Cluain mic Nóis was burned by Muintir-Tlamain, i.e. by Cucaille Mac Aedha’.

The records 0f the Viking presence in Ireland are mainly recorded in the Annals and in Cogad Gaedel re Gallaib.

Hit-and-Run.

A major shock went through Christendom across Europe with the devastating Viking raid on Lindisfarne in 973AD. It was not long before Ireland was visited with the first raid on Rathlin Island in 975AD. This was the start of hit and run raids carried out on Irish monastic sites between 795 – 825 AD. Most of these raids occurred during the summer months.

Early Viking Raids on Ireland

Longphorts / Overwintering.

There are a number of definitions for longphorts – Ó Corráin talks of a defended ship harbour, Clarke suggests an emporium or trading station, and de Paor of a shore fortress. The RIA Dictionary defines a longphort as a camp, encampment, temporary stronghold, a mansion, princely dwelling, stronghold or fortress.

Viking sites are referred to by a variety of other terms, including dún, caisteoll and island. The different terms may simply describe their function.

Longphorts have been based on navigable Irish rivers, setting up a settlement at a D-shaped enclosure where a significant portion of the site is defended by the river itself.

An archaeological dig by UCG in 1982 at Ballaghkeeran, Lough Ree, Co Westmeath failed to produce enough evidence that a Viking longphort had been constructed there.

There is no agreed number of longphorts in Ireland, very few have been excavated so exact analysis and dating is not available. Sometimes placename evidence, such as at Athlunkard Co. Limerick provide clues. Longphorts have also been found in Scotland and northern England.

Why were the Vikings raiding?

The simplistic view is that the raids coming out of Scandinavia were the result of internal conflicts in their own regions. The Vikings from Norway headed west and south covering the Scottish isles, Scotland and then eventually to Ireland. The Danish Vikings landed and eventually established a kingdom in England, a situation where they held control for about 200 years. Finally, we had the remaining Scandinavian Vikings who travelled down the two great rivers of Eastern Europe, the Dnieper and the Don, reached the Black Sea and established trading relationships with Islamic Constantinople that later linked back to Ireland.

Viking expansion across Europe, Wikipedia.

Vikings were particularly interested in monasteries because they were likely to contain valuable loot, but particularly people who could be sold as slaves. It also appears that the Vikings knew exactly where Irish monasteries were located and regularly their arrival coincided when particular religious events were underway. From other evidence they were also after cattle and very occasionally the gold and silver in the monasteries.

Map of Limerick and Athlunkard, Cathy Swift, MIC

It is assumed that longphorts were built before the longer-term Viking settlements or towns were established. The Annals of the Four Masters for 841 says ‘a fleet of Norsemen on the Boinn, at Linn Rois (Rossnaree). Another fleet of them at Linn Saileach (unknown), in Ulster. Another fleet of them at Linn Duachaill (Annagassan, Co. Louth)’. In many cases towns were built on top of the longphorts e.g. at Dublin and Cork. In the case of Limerick and Waterford the eventual town was built down river from the longphort.

For Limerick the likely site of the Viking longphort settlement is situated just north of the confluence of the river Shannon and its tributary the Abbey river, opposite St. Thomas’ Island and would have been an ideal location for an overwintering settlement, easy to defend and close to a crossing point. It is situated about 2km north of today’s Limerick city. John O’Donovan suggests that the name is a corruption of Ard and Longphort. The site is D shaped and Catherine Swift from MIC has dated the site to between 840 and 930AD.

Artefacts have been discovered on the site and also from St Thomas’s Island nearby. A Viking silver weight was found directly opposite the site at Corbally. Kelly and O’Donovan theorise that St Thomas’s Island may form part of the complex. No dateable material has been found in the enclosure itself and therefore there is no direct link to the Vikings. From 837AD the Vikings started to sail up the rivers of the Liffey, Boyne, Foyle, Bann, Barrow and Shannon. Indeed, there are records of Viking fleets going up the Shannon as far as Lough Ree.

The foundation of the city of Limerick, however, is generally dated to 922AD, when the Viking leader Thormodu Helgason established a permanent base on King’s Island, this is the location where King John’s Castle now stands.

Settlement.

Fairly quickly after 850AD Viking overwintering settlements became permanent, year-round. There would have been regular contact with the local Gaelic chieftains as the Vikings would have needed local food and would have introduced trade, initially on a barter basis. These full-time settlements grew into Ireland’s first towns and the hinterland would have been heavily influenced by the Viking presence. Generally, over time these towns developed into cities. From their towns the Vikings continued to raid along the Irish coastlines and through the inland river systems.

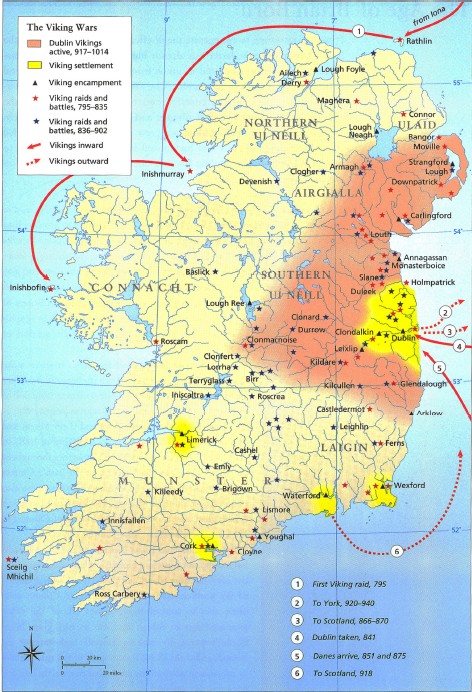

Map of Ireland with the Viking areas, Sean Duffy, TCD.

In general, this was the extent of Viking settlements in Ireland.

In England a Danish Viking army of some 20,000 soldiers arrived in East Anglia in 865AD. This army first attacked Wessex and then the remaining Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. They then established an administration, based on Danelaw and with headquarters in Jorvik (York). The Danish invasion was finally defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge during the Norman Conquest in 1066AD and had lasted some 200 years.

The northwest coast of France was repeatedly devastated by raids from Danish Vikings from the 8th century on, and, as its Carolingian rulers became weaker, the Vikings penetrated farther inland in the course of their raids. Finally, in 911AD the French king Charles III conceded the territory around Rouen and the mouth of the Seine River to Rollo, the chief of the largest band of Vikings. Over time the Viking Dukedom of Normandy acquired neighbouring territories in a series of wars.

Map of Vikings in France and England, Wiki Commons.

William, Duke of Normandy and a distant successor to Rollo, mounted a successful invasion of England in 1066, becoming William I of England (William the Conqueror) and thus united the rule of England and Normandy. By 1169AD other Normans, mainly from Wales, had been invited to Ireland as mercenaries to sort out a local difficulty, they never returned to Wales.

The Shannon.

The River Shannon rises in Co. Cavan and flows for 260 km before flowing into the Shannon Estuary at Limerick City. An unusual feature of the Shannon river is that it is remarkably flat, with the majority of the fall in height taking place on the 24 km stretch between Killaloe and Limerick City.

Dáithí Ó hÓgáin identifies the name of this river as a Bandéa (goddess) from an ancient text. He describes its original Celtic name as Senuna, meaning ‘the old honoured one’.

There are more than 1,600 lakes in the Shannon region but less than 50 of them are over 1 km2 in area. The largest lakes are Lough Derg, Lough Ree and Lough Allen.

The Shannon is the easiest entry point to the interior of Ireland by water. Limerick provided a springboard for raids up the Shannon, affecting areas on both sides of the river. The Vikings used the Shannon as a route to attack as far north as Lough Erne but they also appear to have attacked by land, especially in Connacht, Offaly and Westmeath.

How did they ascend these rivers? The Shannon falls swiftly 120 feet below Killaloe. Viking long boats were surely too heavy to portage. The Karve was a troop carrier up to 70 feet in length with up to 16 oars. The Knarr was a cargo ship that could take livestock and goods, 50 feet in length and have a much smaller crew. Perhaps, for the Shannon, they built shorter, lighter boats that were easy to navigate inland? However, no remains of such boats have been found.

Map of Shannon catchment area, Wiki Commons.

Pre-Viking Limerick

Human activity in the Limerick area can be traced back to the earliest known burial in Ireland and is dated to 7,530 – 7,320BC. This was at the bend of the Shannon river at Hermitage, Co. Limerick. Later, the famous Bronze Age complex at Lough Gur was dated to 2400 – 1800BC. Prior to the arrival of the Vikings the wealth of the local monasteries can be seen, for example, from the Ardagh Hoard, dating to 750AD. At the time of the Vikings there were over 2,200 ringforts in Co. Limerick, indicating a high population level and strong agricultural activity.

Limerick/Hlymrekr.

The name Limerick or Klymrekr was the Viking kingdom which existed from 845 to 977AD. Although there are some references to a ninth-century settlement in Limerick, the permanent settlement appears to have been established in 922AD by the Viking Jarl Tamar Mac Ailche also known as Þórir Helgason to his Norse followers.

The early Vikings to settle in Hlymrekr arrived in 845, and, in 922 the Vikings sailed up the River Shannon to plunder ecclesiastical settlements from Lough Derg to Lough Ree.

Kings Island, Limerick.

The first permanent settlement was probably located on King’s Island, protected by the Shannon and Abbey rivers. This location was very accessible for those arriving by sea as well as the starting point for excursions up the Shannon. From early days this settlement became known as a trading post where luxuries could be traded to the Gaelic elite.

Very early on, Tamar Mac Ailche sent his men inland to Roscrea and Monaincha in Tipperary. This is described in Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh Chapter XV: ‘the shrine of Patrick broken, and the churches of Mumhain plundered, [the foreigners] came to Ros Creda (Roscrea) on the festival of Paul and Peter, when the fair had begun; and they were given battle, and the foreigners were defeated through the grace of Paul and Peter, and countless numbers of them were killed there’. The Vikings were not invincible and did loose many battles with the Irish.

The Shannon Estuary Rivers.

We must not forget the Shannon estuary and the tidal rivers that flow into it. These rivers were also visited by the Vikings. On the norther bank of the estuary the significant local river is the Fergus, on the southern back we have the Maigue, Deel and Feale rivers – all visited by the Vikings.

Join us next week for part 2 in this series. Our thanks to John Dolan