As mentioned earlier there are many histories of hurling in recent times, particularly county and local club histories. A major and broad history of hurling, Scéal na hIomána was produced by Brother Liam Ó Caithnia in Irish and was published in 1980, but was left largely unappreciated for decades. Ó Caithnia’s history was an exhaustive work, the definitive historical account, written initially as an academic thesis, 826 pages long, written in dense Irish with a small print font and included references and appendixes. Over a dozen mentions of Co. Offaly are to be found in the Scéal.

Ó Caithnia spent about twenty years researching hurling in all areas of Ireland and his manuscript led to him being granted a PhD. One of the sources where he found very valuable information was in the Irish Folklore Commission. Many problems presented themselves. Written in Irish it became obvious that many of the words and terms in use had mutated significantly over time. Another problem was that scholars and historians ignored many of these ancient manuscripts until the late 1880s.

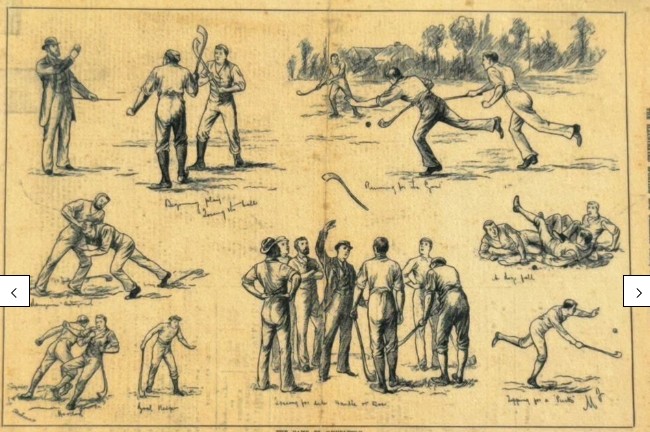

Scéal na hIomána, The illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, Nov 1881.

A surprising element of Ó Caithnia’s research was that the gentry and landowners loved the game as much as the Irish people who laboured on their lands, and with their guidance and generosity, the game thrived for centuries. The game was a battle. Games could last for a week, and the prizes, which included money and barrels of porter, ensured that those who travelled, often barefoot, for miles and miles to see a contest were seldom disappointed.

Ó Caithnia records that Oliver Cromwell attended a game of hurling in Hyde Park, London. A game was played for King Louis IX in Paris. Some of Ó Caithnia’s findings are included below.

Scéal na hIomána by Brother Liam Ó Caithnia, 1980.

The team of the 18th century consisted of 21 men, laid out with three rows of seven. At the middle of the vanguard stood the captain, at least 40 yards from his own goal. The captain was chosen by members of the team. There was no goalie, neither was there a referee. A single goal decided the match.

All evidence indicated the presence of crowds of up to 10,000 people for the championship matches. Matches were announced one month in advance to allow for lengthy journeys on foot, along with the installation of tents, stalls and provisions.

An announcement in the Flying Post for 26th June 1708 says: ‘On St. Swithin’s Day, about three in the afternoon, will be a Hurling Match over the Curragh, between 30 men from each side of the Liffey, for 30 shillings. A barrel of ale, tobacco, and pipes will be given to the hurlers’. In 1748 a game was played in Crumlin between Leinster and Munster with 20 men per team, Leinster won after 45 minutes when a goal was scored.

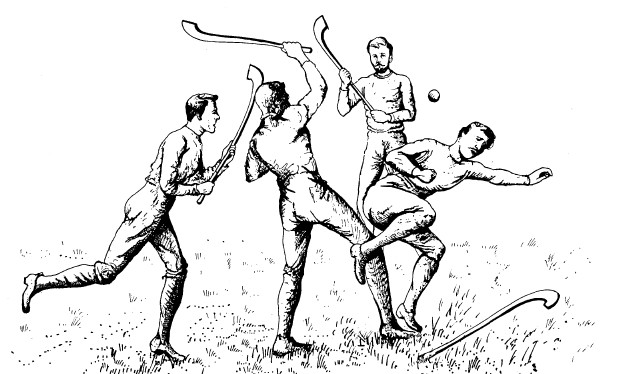

Tussle for the ball. Scéal na hIomána

In the sixteenth century the Lord Chancellor of Britain made a complaint about a number of English soldiers who were speaking Irish and playing hurling. By the end of the seventeenth century at the latest, inter-parish and inter-barony matches were common. The Ascendancy landlords of English descent were organising, developing and fostering hurling all over Ireland, even going so far as to train teams and provide them with uniforms, hurling sticks, trophies, playing fields, prizes and so on.

Having flourished in the 17th and 18th centuries, hurling began to suffer a lengthy decline after the 1798 Rebellion, followed later by the Act of Union. If hurling had a golden age, it was the 18th century. The gentry no longer supported the game, turning instead to rugby and cricket, and the Famine accelerated hurling’s decline before its rebirth in 1884. By 1883 Michael Cusack claimed that ‘no hurling has been played in Dublin…within the memory of the oldest inhabitant’.

Thankfully, an English version of Ó Caithnia’s masterpiece was finally produced in 2024. It is available in the public library system. This is The Epic Origins of Hurling and has been produced by a team including Stephen and Michael McGrath, and scholars Liam Mac Mathúna and Padraigín Riggs. This is an abridged version and translation, it does not include the notes and references of the Scéal. An initial plan to make it available online failed. Up to eight translators took Ó Caithnia’s book and brought it into English. However, additional work was required to synchronise their work and verify the references into a final publishable book.

The Epic Origins of Hurling.

Shinty.

Shinty is derived from the historic game common to Ireland and Scotland, a similar game called Cammag was played on the Isle of Man. There was never one common name for the game in Scotalnd, it had different names from glen to glen. By 1700 the name Shinty was in general use. The sport was played by people in one community, sometimes competing against people from another community.

Shinty Sticks, Wikimedia Commons.

The Shinty ball used today is a hard, solid sphere, consisting of a cork covered with leather. The stick used is called a caman, about 1.1m long and has two slanted faces. You will note that early images of an Irish hurley look very similar. It is typically made from ash or perhaps hickory.

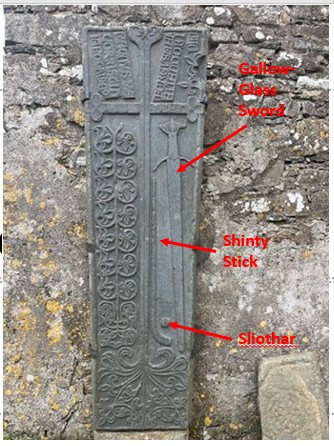

A 15th-century grave slab survives in Clonca church, Inishowen, Co. Donegal, dedicated to the memory of a Scottish gallowglass warrior named Manas Mac Mhoiresdean of Iona. The slab displays carvings of a Claymore (sword), a caman (for playing shinty as opposed to hurling), and a sliotar.

Grave slab of Manas Mac Mhoiresdean of Iona.

The stone slab has an inscription that reads: ‘Fergus Mak Allan Do Rini in Clach Sa Magnus Mec Orristin Ia Fo Trl Seo’ which translates as ‘Fergus MacAllan made this stone; Magnus Mac Orristin under this.’ The depiction of a sword alongside a shinty stick and sliotar on the gravestone illustrates how sport was deeply connected to and ingrained within the warrior culture in medieval Ireland.

Emigrants to Canada took their sport with them and during the harsh winters played on ice – from which the sport of ice hockey was born.

The Welsh game of Bando.

Closely linked to hurling and shinty, at its prime Bando was played on a regular basis across south-west Wales. It was played informally by children in the streets as well as more formally by adults of one parish challenging an adjacent parish. Apparently, David Lloyd George played the game. Popular in Glamorgan in the 19th century, the sport all but vanished by the end of that century.

Bando stick, Museum of Wales, Cardiff.

Hurleys.

The Seanchás Mór (Brehon Law) states that the son of a rí (local king) could have his hurley hooped in bronze, while others could only use copper. A later (eleventh/twelfth-century) commentary on the law text Cáin Iarraith claims that the son of a king should have a cammán ornamented with silver, while the son of a lord should have a stick ornamented with bronze. It was illegal to confiscate a hurley.

The oldest known hurley, perhaps, was discovered at an archaeological dig at Skehacreggaun near Mungret, Limerick. This carved piece of wood was taken from the trunk of a willow tree and radiocarbon dated to 593 – 650 AD. It measures 135cm in length, and was probably unfinished.

Skehacreggaun willow stick. Archaeology Ireland, Autumn 2025.

One definite hurley from the Middle Ages is an alder-wood stick from Derries, near Edenderry, Co. Offaly. It was 95cm in length and 6.5cm in width, and was dated to 1467–1635AD.

Hurling stick from Derries, Edenderry, Co. Offaly. NMI

Sliotars.

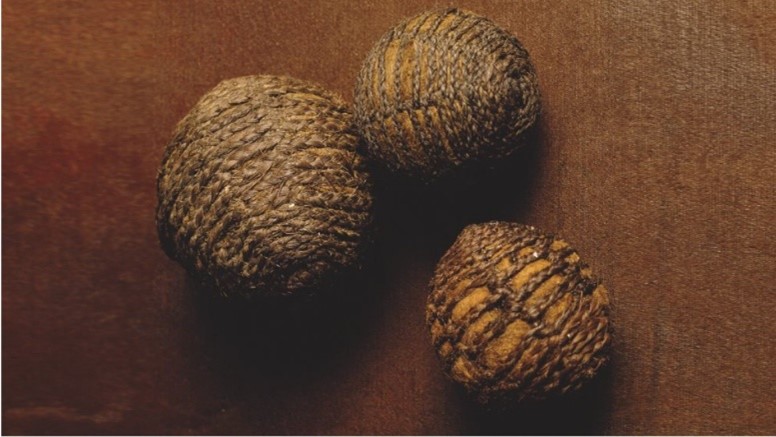

Apart from the metal balls – gold, silver, bronze – of the pre-Christian literature there is little physical evidence of them, though the earliest archaeological evidence dates hurley balls to the latter half of the 12th century. The key was that a hurling ball had to have the ability to bounce.

Early (pre-GAA) sliotars used various materials, depending on the part of the country, including combinations of wood, leather, rope, animal hair and even hollow bronze.

Hair hurling balls, Sligo. NMI

A recent report from the National Museum says ‘There’s hair hurling balls that date back to the 15th and 16th centuries. They’re in a couple of collections across the country, they’re in Kerry County Museum, they’re in the National Museum of Ireland and they have been radiocarbon dated to tell us that hurling was happening in the 15th century’.

There was no specific standard for the size or weight of sliotars. The man credited with initial standardisation of the sliotar is Ned Treston (1862–1949) of Gort Co. Galway. He was selected to play in a match between South Galway and North Tipperary in February 1886 in Dublin. Prior the game, there was debate between the teams as regards the size of the sliotar. Treston made a sliotar at a nearby saddler, which was used in the game, and went on to be a prototype for subsequent sliotars

The National Folklore Collection has records of wooden hurling balls found in Meath, Longford, Leitrim, Donegal, Galway and Wexford.

Building the Rule book.

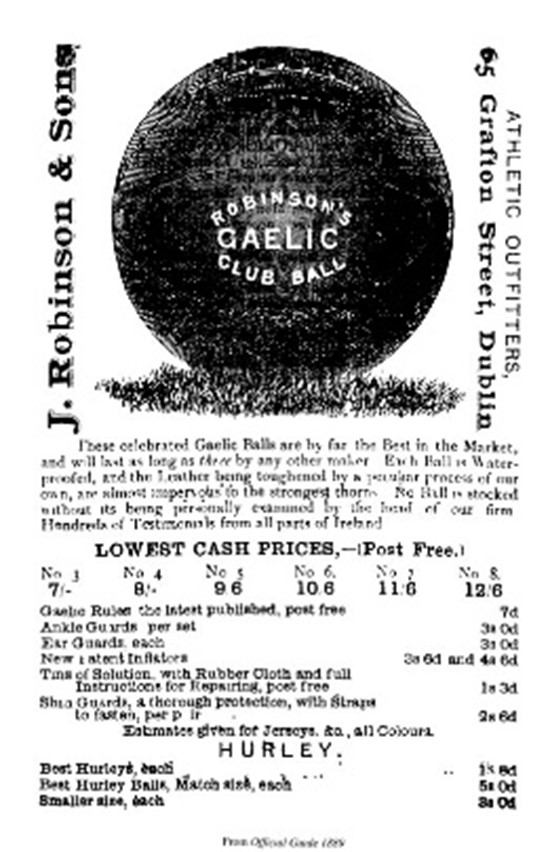

Establishing the GAA in 1884 was only the start of a series of processes. One of the most urgent was the establishing and publication of the GAA rule book that would cover hurling, football and administration.

The rule book issue was a major problem in that there was never any definition of what was a match, how many players could be involved, rules had been invented on the day and the game differed significantly from place to place.

Off to the match. Scéal na hIomána.

The Irish Examiner has a story: when Roscomroe beat Frankford in that 1888 semi-final match in the King’s County championship, the players were so thrilled with the victory that they spent the afternoon drinking despite the fact that they were due to play ‘Dunkerrin, Monegall and Barna’ later in the day. In part, of course, this provided the ideal excuse for subsequent failure, as a famous local ballad in Roscomroe concluded: ‘’Twas the liquor that defeated us!”, a day out in King’s County was joined by a day out in Tipperary. In the 1880s, the local curate in Dunkerrin, Fr. John Maguire, was a well-known lover of hurling who celebrated a hurling match by killing a pig and boiling six stone of bacon for the occasion.

However, the GAA were beaten to the punch by the Killimor club, Ballinasloe, Co. Galway. The Killimor Rules were published as a one-page notice with ten points in 1869. Previously, before each game the duration or total number of goals to be played was agreed by the captains of both teams, agreed on a local basis. An Irish Times account described a match at the club where Killimor ‘slashed in a reckless and savage manner’ when winning a match.

Killimore Hurling Rules, 1869.

Other early GAA rule books include The Trinity College, Dublin Laws of Hurling 1870, The Irish Hurley Union 1879, The Dublin Hurling Club 1883 and The GAA Rules 1885.

About the 1888 Rule Book

GAA Rule Book, 1888.

Key Features of the 1888 GAA Football Rules

- A series of definitions, including pitch dimensions, how many players per team, umpires, referees, goal-posts etc.

- How the games were to be played and the rules of play

- Scoring: A goal was scored when the ball went between the goalposts and under the crossbar. A point was scored when the ball went over the crossbar or over the goal line within 21 feet of a goalpost.

- Player Formation: Prior to a throw-in, teams would stand in two ranks, opposite each other in the center of the field, and hold hands with opposing players.

- Match Decision: The game was decided by the number of goals scored.

- What was banned: head-butting, tripping etc. Nails and iron tips on both football and hurling boots were forbidden.

Attached to the draft 1886 Rules are two recommendations. ‘The dress for hurling and football is to be knee-breeches and stockings and shoes or boots’. Also, ‘All dress materials and other articles required in the games to be, as far as possible, of Irish Manufacture’.

Adoption of the 1888 rules was particularly slow in all regions. One regular problem was the frequent late arrival of teams, even for All-Ireland Finals! It was not until 1910 that the scheduled games were actually played within the year of the designated national championship.

An ad from Robinsons & Sons, Grafton Street, Dublin.

POSTSCRIPT: RTE report of the most recent Hurling-Shinty International just held on 15th October 2025. Read at https://www.gaa.ie/article/ireland-edge-out-scotland-in-hard-fought-hurling-shinty-international.

The Ireland players and management celebrate after victory over Scotland in the Hurling-Shinty International Rules series match at Bught Park, Inverness.

The Táin in the Book of Leinster was translated by Cecile O’Rahilly is available in full. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T301012/text001.html