Archaeologically speaking there are many different types of enclosure in Ireland, many dating from some thousands of years ago and built for many different reasons. Some of the different types include:

Henge. A large, enclosed, prehistoric, circular or oval area usually over 70m in diameter which is defined by an earthen bank and a (usually internal) shallow but broad ditch. They can contain a variety of internal features including timber or stone circles. They are ceremonial/ritual monuments and date to the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (c. 2800-1700 BC). They have between 2 – 4 entrances. There are no henges in Offaly.

Just 18 henges survive in Ireland today, one of the largest is at Ballynahatty (7 acres) just SW of Belfast and which contains a small passage tomb containing the remains of a unique Neolithic woman. The most well-known henge is probably that at Dowth at Brú na Bóinne.

Ballynahatty and Dowth Henges

Barrow. A circular or oval raised area (generally over 1m above the external ground level) with an external ditch and sometimes an outer bank. They contain burials and were in use from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age (c. 2400 BC – AD 400). There are at least seven different types of barrow in Ireland.

There are 41 barrows in Offaly, at least 30 ring-barrows and 5 bowl barrows.

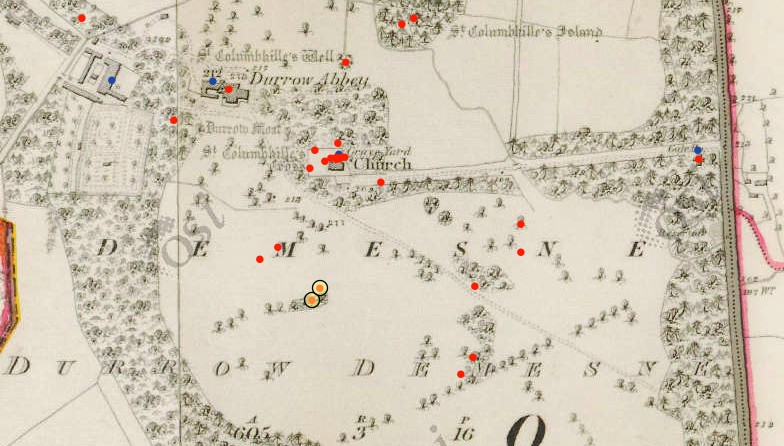

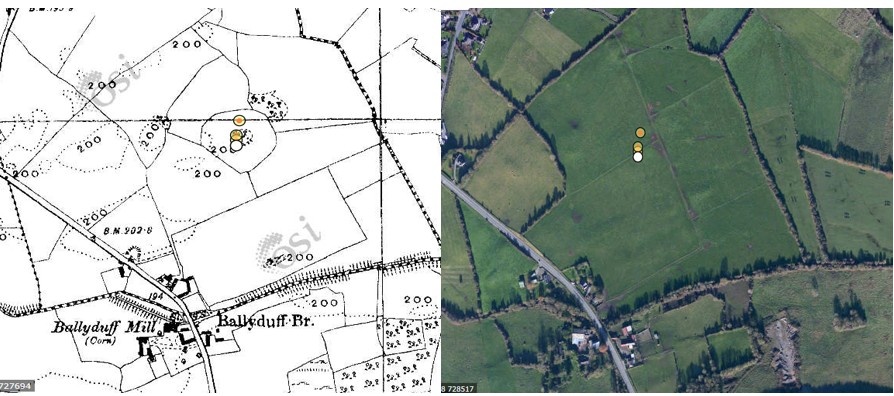

Durrow Abbey with two ring-barrows side by side (yellow dots), OS map

Coolcreen in the Sliabh Blooms with 5 barrows adjacent to one another, OS map

Ring Ditch. A bedrock cut ditch or trench of circular or penannular plan, usually identified through aerial photography either as soil marks or cropmarks. When excavated, ring ditches are usually found to be the ploughed‐out remains of a round barrow where the barrow mound has completely disappeared, leaving only the infilled former ditch.

There are 6 ring ditches in Offaly none of which are visible at ground level. Sometimes, they only appear as crop marks on the ground.

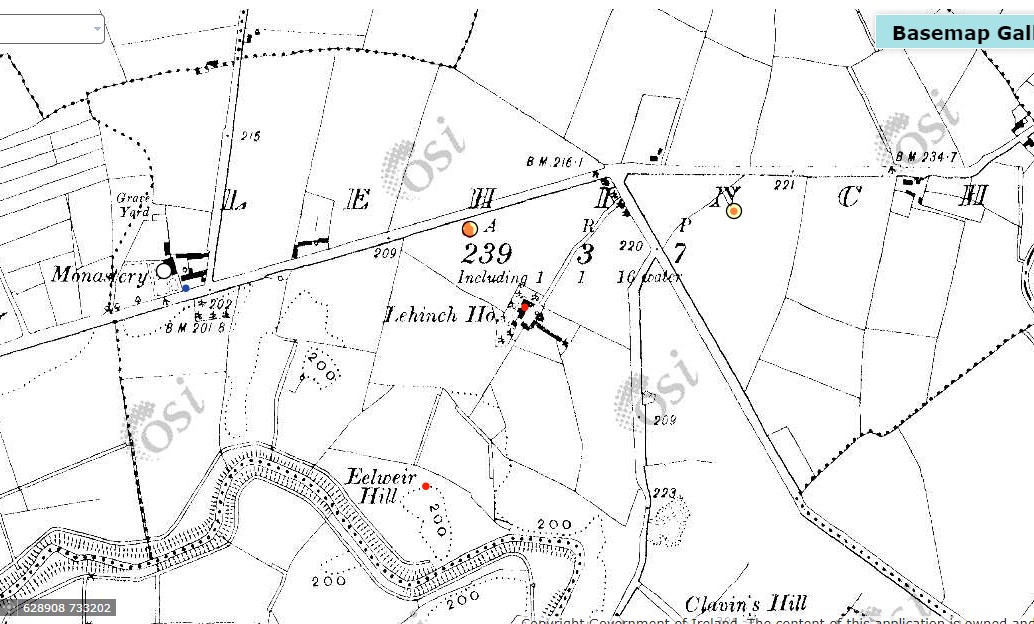

Two ring-ditches (yellow dots), Lehinch near Clara, OS map

Ringfort or rath. A roughly circular or oval area surrounded by an earthen bank with an external ditch. Some examples have two (bivallate) or three (trivallate) banks and fosses, but these are less common and have been equated with higher status sites belonging to the upper grades of society. They functioned as residences and/or farmsteads and broadly date from 500 to 1000 AD. Ringforts have seen the most destruction in recent times, primarily to release the enclosed space for agriculture even though protected by law as National Monuments. Ringforts made from stone are called cashels.

There are 199 ringforts in Co. Offaly, mainly clustered in the south of the county.

Three ringforts, Broughal, Co Offaly, OS map

Hillfort. A large enclosed area that is usually encompassing between 2 and 22 hectares (diam. exceeding c. 160m). Hillforts are always located in high upland terrain and are very prominent locally. They are defined by an earthen bank/banks or a wall/walls and can be circular, oval or more irregularly shaped if following the contours of a hilltop. In the case of bivallate or multivallate examples, the banks are often widely spaced. They may have been important ceremonial or tribal centres and/or permanent or temporary settlements. Some examples date from the Early Neolithic (c. 3600 BC), others from the Middle to Late Bronze Age (c. 1400-500 BC) with examples of reoccupation in the later Iron Age (c. 100-400 AD).

There are two hillforts in Offaly, one at Ballymacmurragh NE of Longfort village, it is made of two banks and is almost surrounded by forestry. The second is close by at Aghancon and is made up of two widely separated banks and is one of the largest on the island covering 14 acres.

Ballymacmurragh and Aghancon Hillforts, OS map

How to find enclosures.

There are many techniques used to identify enclosures.

Where archaeological remains are suspected but where no evidence is visible at ground level the use of ground level geophysics can reveal detailed layouts of buildings, sites, roadways, enclosures, etc.

Aerial photography allows us to compare sites over many years, commencing in the middle of the last century particularly with the work of Leo Swan and Norman & St Joseph of Cambridge University. Pioneer JK St. Joseph qualified as a geologist and then lectured in Cambridge University. During WWII he analysed photographs taken by RAF photographers. Using his wartime experience he understood the potential of aerial photography to analyse archaeological sites. One of his earliest publications was Monastic Sites from the Air published in 1952.

Aerial photography has also identified enclosures through cropmarks where nothing is visible at ground level. Cropmarks generally appear when crop growth is aligned with dry conditions.

Leo Swan was the first to exclusively examine Irish ecclesiastical sites from the air starting in 1971. He combined his aerial research with study of the six-inch OS maps. In addition, he had access to the documentary evidence from the Early Medieval period. He identified 400 ecclesiastical sites through photography and added another 200 sites through his field work.

Here is a link to Leo’s photos for Co. Offaly. https://lswanaerial.locloudhosting.net/search?query=offaly

Cambridge University conducted aerial photography of the UK and Ireland after WW2. Cambridge University Air Photos of Co. Offaly are available here https://www.cambridgeairphotos.com/search/?lonLat=&search=offaly

Someone with time on their hands can go and compare the early OS maps with these early aerial photos and today’s satellite photos and identify the destruction of the very large number of archaeological sites in their own locality.

One of the other major contributions that Leo Swan made to the archaeological investigations of early church sites from his aerial and field work was to produce a list of features which are consistently found on these sites and lists them in order of frequency:

- Evidence of enclosure

- Burial area

- Place name with ecclesiastical element

- Structure, or structural remains such as church or Round Tower

- Holy well

- Bullaun stone

- Carved, shaped, inscribed, or decorated stone cross or slab

- Line of townland boundary forming part of the enclosure

- Souterrain

- Pillar stone

- Founder’s tomb

- Associated traditional ritual or folk custom

- Radiating road network

- Triangular market area, commonly but not always on the east

Swan suggests that there will be four or five of these features that survive in most cases.

For hundreds of years the enclosures remained untouched whether through folklore – the Púca, Fairy Fort or an area of liminality, the bridge between the living and the dead. It was the arrival of the tractor pulling the plough that rubbed these ancient sites off the landscape.

ECCLESIASTICAL ENCLOSURES

What do we mean by early Irish churches? The early churches were made of wood, no archaeological trace of these wooden churches have survived. They were simple, rectangular shaped with one door and one window (perhaps) facing east to west, with the door pointing to the west. Stone churches arrived around 500 – 800AD with almost the same layout as the wooden churches. Church architecture remained the same until the arrival of the Continental monks and the reforms of the Irish church in the 1100s. Only a handful of early ecclesiastical sites have been fully excavated, 41 have had partial/limited excavations carried out.

How many ecclesiastical enclosures are there in Co. Offaly? The National Monuments database has a list of 22 ecclesiastical enclosures in Offaly while Elizabeth FitzPatrick in her 1998 paper ‘The Early Church in Offaly’ lists 6 enclosure sites with a possible 5 others. Mervyn Archdall (1723 – 1791) lists 32 ancient Offaly churches in his Monasticon Hibernicum, many of the names he gives can no longer be located today. Later FitzPatrick and O’Brien list eight very large enclosures in their 1998 book on the Medieval Churches of County Offaly.

Swan suggests that there are at least 2,000 early church sites in Ireland. The Stout husband and wife team suggest that there were over 5,500 pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites in Ireland. In addition, it is suggested that over 6,000 townlands contained the name Cill in their placename.

What is an Ecclesiastical enclosure? A large oval or roughly circular area, usually over 50m in diameter, defined by a bank/banks and external fosse/ditch or drystone wall/walls, enclosing an early medieval church or monastery, its graveyard and its associated areas of domestic, agriculture or industrial activity. These date to the early medieval period (5th-12th centuries AD). Sometimes hedges, field fences and field boundaries have replaced the original enclosures.

The Early Irish Church developed independently from the European Roman model which was based on the cities of the Roman Empire, connected by the great European road systems. These European cities had a church centre led by a bishop. The Irish system developed independently to the degree that major reform was demanded by the European and English Church in the 12th century.

These early church establishments are not to be confused with the later and very different medieval abbeys and friaries of the Continental orders that arrived in the 1100s.

A circular pattern for the layout of early Irish church sites was adopted from an early date. There may not have been a written down plan but there was a general pattern almost universally accepted to which the early sites seem to have conformed. These church sites were surrounded by banks of earth constructed in a way used for constructing ring forts, so the skills for construction were readily available. Many church sites had two banks with a very small number having three banks. It appears to have been a universal pattern. The enclosure contained the church, burial ground, other church structures such as round tower and high cross.

Only a small number of Offaly churches retain enclosures visible in the landscape today. However, as discussed earlier there are many techniques available for identifying where enclosures may have been robbed away. Many are very similar in size to ring forts while some of the largest sites are comparable with the largest hillfort.

Many problems exist with a mere surface examination of these enclosures, the most important of which is their dating. Without excavation it is nearly impossible to give a date to the construction of an enclosure. In addition, many of these enclosures display later mediaeval occupation and farming traces at surface level.

Where there was insufficient earth to make an enclosure a number of church sites, particularly on islands in the west of Ireland designed their enclosures and built them in stone. Examples include Skellig, Ilauntannig and Inismurray. These church sites survive today particularly as pilgrimage sites.

Holy of Holies and Sanctuary.

Two features of the Christian church that appear early are the concept of the Holy of Holies and the concept of Sanctuary. Both would have been strange to the Irish people used to the Druidic rituals usually held in groves/woods. Conversion to the new church and its rituals was slow and took hundreds of years to complete, many of the older Celtic rituals survive to modern times – reverence to the holy well, the rag tree and the perpetual fire.

The Holy of Holies is a term from the Hebrew Bible and relates to the inner sanctuary of the Tabernacle where God’s presence appeared in Israel. The area held the Ark of the Covenant which contained the ten Commandments, given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai.

The concept of Sanctuary stretches back to the Cities of Refuge of the six Levitical towns in Israel and Judea in which the perpetrators of accidental manslaughter could claim the right of asylum. Mention of refuge and sanctuary can be traced back to the Old Testament and the Books of Deuteronomy, Exodus, Joshua and Numbers.

Charles Doherty (UCD) has suggested that the Irish had a concept of sanctuary based on the biblical ‘city of refuge’ whereby the monastic site is considered a holy of holies at the core, around which are areas of sanctuary that decrease in importance the further you move away from the centre. Doherty describes the first area of sanctuary as Sanctissimus, the second Sanctior and the third as Sanctus.

With the growth of Irish ecclesiastical settlements, it became increasingly important to protect the sanctity of the holy area, prevent the violation of graves, control the influx of pilgrims and protect the wealth of the church. In addition, it was necessary to protect those fleeing and seeking sanctuary and preventing raids from other churches and princes. In Europe the concept of sanctuary was intimately linked to the right of asylum from the 5th century. A Roman law, passed in 419AD set the sanctuary boundary to a circuit of 50 paces around the place of worship. It is not clear when the concept of sanctuary expired.

Were these enclosures defensive? If so, they were a miserable failure. We know the accounts of how easily the Vikings raided the monasteries. Less well known are the accounts of raids by the Irish on the monasteries. The Annals are littered with such raids. One monastery in Offaly is recorded many times. Clonmacnoise did not appear to like its neighbours – Birr, Durrow or Kinnitty.

- U760.8 A battle between the communities of Cluain Mac Nois and Biror in Móin Choise Blae.

- U764.6 The battle of Argaman between the community of Cluain Moccu Nóis and the community of Dermag (Durrow), in which fell Diarmait Dub son of Domnall, and Diglach son of Dub Lis, and two hundred men of the community of Dermag. Bresal, son of Murchad, emerged victor, with the community of Cluain. Both quotes from the Annals of Ulster.

- And in 842 Kinnitty and Clonmacnoise were at war. So much for the Isle of Saints and Scholars!

Durrow also suffered: burned in 1095, 1153 and twice in 1155. In 1175 Durrow was devastated by Hugh de Lacy of Meath.

The Annals of the Four Masters describe other destruction in Offaly.

- M800.10 Cill Achaidh (Killeigh) was burned, with its new oratory.

- M952.11 Saighir Chiarain was plundered by the men of Munster.

- M1548.9 Saighir and Kilcormac were burned and destroyed by the English and O’Carroll

There are many other cases where sanctuary was ignored by the local Irish lords such as described in the Annals

- AI1180.3 Ard Ferta Brénainn (Ardfert) was plundered by the Clann Charthaig, and they carried off all the livestock they found therein. They put many good people to death inside its sanctuary and graveyard; but, indeed, God avenged that, for a large number of those plunderers were forthwith slain.’

Another mention in the Annals of Ulster recount an Irish raid on Donaghpatrick, Co Meath

- U746.11 Violation of sanctuary at Domnach Pátraic, six captives being hanged.

An attempt to halt the slaughter of monks and laity and re-establish the sanctity of sanctuary was attempted by Adomnán at the Synod of Birr in 697 AD. Adomnán, then abbot of Iona, collected an assembly of religious and royal leaders headed by Loingsech mac Oengusso then Cencl Connaill, King of Tara. The synod passed Cáin Adomnáin also known as the Law of the Innocents. The law provided sanctions against those who killed children, clerics or farm labourers within a church sanctuary, however it failed in its implementation.

THE ENCLOSURES IN OFFALY

Durrow

Durrow, the Columban site was the location of the murder of Hugh de Lacy in his attempts to build a fort and establish his claims to the lands of Mide (Meath). Whether his plan was to build a Motte and Bailey or a stone fort such as that at Trim is unknown. However, the earlier Irish enclosure can still be seen as cropmarks in the field to the south and east of the church.

The outer enclosure has a double bank with a ditch/fosse in between, perhaps, 500m in diameter. Did the inner enclosure represent the area of sanctuary?

The Life of Colmcille tells us that Colmcille requested Cormac O Liathain that the abbot ‘set in order the monastery and enclose it well’. Elsewhere, it mentioned that 150 workers erected an enclosure that ‘there might not be a breach therein’ and that the oak trees of Dar Magh were cut down to provide stakes for protection of all sides of the monastery.

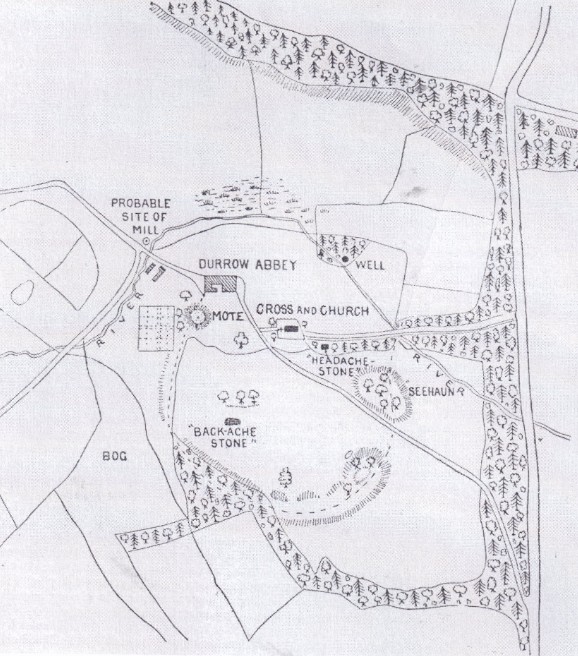

The following drawing was made by Sterling de Courcy Williams in 1899. The remains of the enclosure can be seen south of the church and swinging west in the direction of the motte.

A story in the Life of Colmán of Lynally recounts that a raiding party from Durrow stole earth from Lynally’s enclosure that Colmán had brought back from Rome. Did they put it into their own enclosure?

Sterling de Courcy Williams drawing of the Termon of Durrow, 1899 & Leo Swan photos1

Clonmacnoise.

There is no trace of the first great monastery of St Kieran. This was one of the most important early schools, founded at the edge of the River Shannon in 544.

Seirkieran/Saighir.

Like Birr, Seirkieran sat on the old provincial border between Mumu (Munster) and Mide (Meath) and suffered from regular tensions particularly with the southern Ui Neill. Impressive substantial earthen banks, separated by a ditch/fosse still surround the church at Seirkieran, enclosing an area of about 12 ha.

Geoffrey Keating has an account of the building of an enclosure at Seirkieran, ‘at this time Sadhbh, Queen of Ireland, wife of the Ard Righ Donnchadh, son of Flann Sionna and daughter of Donnchadh King of Ossory grieved that Saighir the burial place of her ancestors lay open and defenceless while so many other famous churches in Ireland were encircled by walls induced her royal husband to send a number of masons from Meath to erect a suitable wall of stone around the cemetery’. This account implies a stone wall around the Seirkieran graveyard; however, archaeology has failed to find this wall. It confirms other accounts that Seirkieran was the burial place of the Kings of Ossory at this time; Keating states that ‘the burying place of the kings of Osruighe was at Saighir Chiaráin’.

Photos of Seirkieran by Leo Swan2

Rahan.

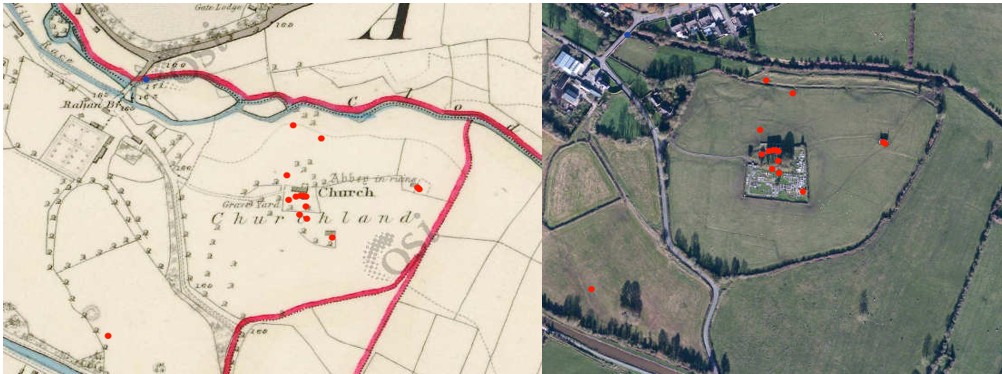

This site contains the church of St Carthage in its original enclosure with the original earthen ramparts around it. The monastery is inside a large D shaped enclosure with the River Clodiagh forming the northern boundary. The enclosure is 500 m x 325 m, covering field boundaries to the south, west and east. The outer bank is made from earth with an external bank/fosse. In 1870 Thomas Stanley described the inner enclosure as having two earthen banks with intervening fosse.

In recent times Dr Paul Gibson has carried out extensive geophysical surveys of the interior which reveals sub-rectangular inner enclosures.

Rahan from early and current OS maps

Killeigh.

The enclosures around Killeigh are probably the largest in the country. Many elements of them have survived, the remainder ploughed out. The full extent of the enclosures is best seen through aerial photography and survives in the south east of the village. Another part can be seen to the south west of the village in a field to the west of a lane that runs past Abbey Farm. Otherwise, elements of the original enclosures are seen as ragged cropmarks from aerial photography.

Artistic view of Killeigh Historic Landscape published on Offaly.ie

Cooleeshill.

Close to Roscrea this enclosure is an impressive cashel, built of stone on the basis that stone was more readily available than earth. This site is dedicated to St. Kieran of Seirkieran.

Cooleeshil from OS maps

Wheery

Another early site with a river as a significant element of the enclosure, similar to Durrow and Seirkieran. Earlier called Kilwheery. Situated on the flood plains of the river Brosna the river provides the southern boundary of a D-shaped enclosure measuring 55m x 35m at maximum. From an account in the Kilkenny Archaeological Journal, during drainage works in 1849 a bell, enclosed in a shrine was found in a pool in the Brosna just beside the site.

Maps from the early OS surveys and modern satellite photo

Kildangan – Tihilly

Tihilly is located between Tullamore and Durrow. Human bones are said to have been found in the site which was levelled during the last century and is no longer visible at ground level. The ecclesiastical enclosure consisted of a large circular area enclosed by an earthen bank which acted as a circular field boundary. The site seems to have contained a graveyard and a holy bush. Folklore stories collected in the 1930s describe the annual Patron Day rituals carried out at Tihilly. The comparison between the 1830s OS map and the modern photo identifies the destruction to the original church site for agricultural purposes.

Maps from the early OS surveys and modern satellite photo

Fancroft.

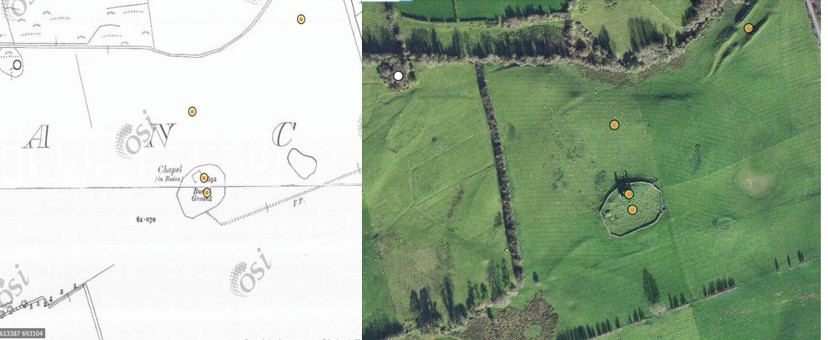

Early church enclosure within an archaeological rich landscape containing church and graveyard. There is no modern access road but there is a trace of a sunken road to the NE of the site that may have led to the original church site.

Fancroft early OS map and modern satellite photo

Sources

1 Accessed August 3, 2021, http://lswanaerial.locloudhosting.net/items/show/33524. Shared under license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

2 Accessed December 3, 2021, http://lswanaerial.locloudhosting.net/items/show/34458. Shared under license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)