The pioneering travel book on the Irish canals was Green and Silver (London, 1949) by L.T.C. Rolt (1910–74). Tom Rolt made his voyage of discovery by motor cruiser in 1946 along the course of the Grand Canal, the Royal Canal (fully open from Mullingar to the Shannon, until 1955 and thereafter from 2010), and the Shannon navigation from Boyne to Limerick (happily now navigable up to Lough Erne). The Delanys writing in 1966, considered Rolt’s book to be the most comprehensive dealing with the inland waterways of Ireland.[1]

During the 1940s, and up to the early 1970s the canal candle was flickering but was kept burning by enthusiasts in England and in Ireland. Among these were the late Vincent Delany and Ruth Delany whose book on the Irish Canals in 1966 was a seminal work. As pointed out in the Irish Times in November 1993 Ruth Delany is the most prolific author on the subject of the Irish canals and herself acknowledges that Green and Silver had a profound influence on her. Other writers were Hugh Malet and Colonel Harry Rice – the latter largely founded the Inland Waterways Association. In 1973 Ruth Delany extended the 1966 book with a full-scale study of the Grand Canal which was reissued in 1995 with an update on the previous twenty years.

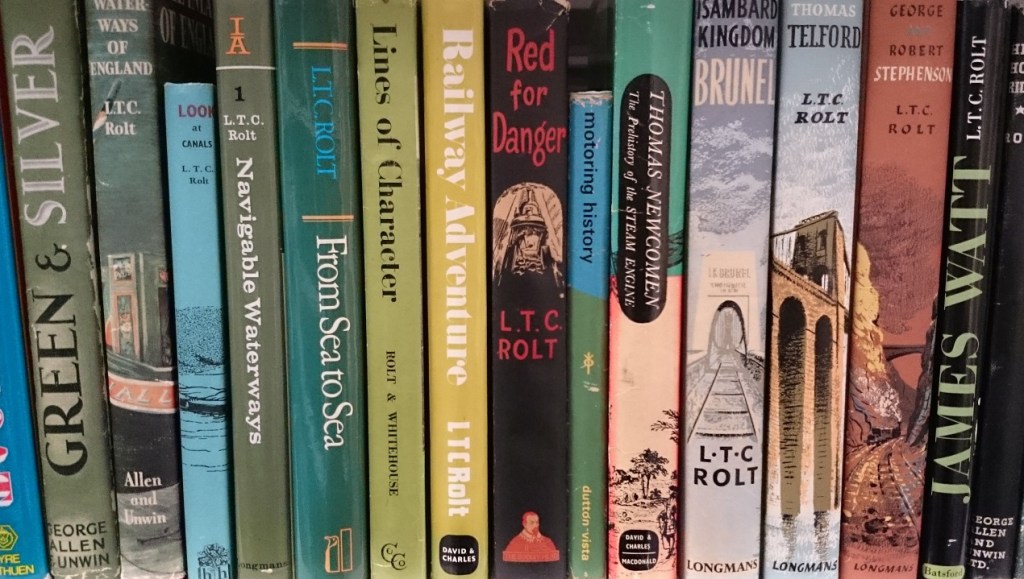

Tom Rolt was born in Chester in 1910 and after working in engineering and with vintage cars he became a full-time writer in 1939. Some of his many books are shown in the attached illustrations while ‘his biographies of great engineers, such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859), are still highly regarded. As a campaigner, activist and champion of industrial heritage Rolt is best known for his involvement with the Inland Waterways Association, the Talyllyn Railway Preservation Society, the Newcomen Society, and the Association of Industrial Archaeology.’[2] On his marriage in 1939 to Angela Orred, daughter of a retired army major. They went to live on his house boat Cressy and in 1944 published Narrow Boat, a passionate evocation of the British canals and those who worked on them. His wife left him in 1951 to join the Billy Smart circus. Two very focused people.

Rolt married secondly the former wife of a boatman and daughter of a colonial civil servant. Over the next fifteen years he published some of the most impressive of his forty works on canals and engineering.[3] He was a founder member of the Inland Waterways Association and one wonders did he ever meet the Athlone based Harry Rice who was largely responsible for founding the Inland Waterways Association of Ireland. Its first officers in 1953 were President, Colonel H. J. Rice; Vice-Presidents, Major General H. MacNeill, Prof. J. Johnston, Prof. J. Henry. T. G. Wilson, S. MacBride, P. J. Lenihan, J. J. O’Leary, J. F. McCormick, G. Shackleton, D. Williams, W. Levinge and A. Turney; Hon. Secretaries, Vincent Delany and L. M. Goodbody. Hon. Treasurer, G.C.M. Thompson. Council. Dr. R. O’Hanlon, Dr. A. Delany. Major E. H. Waller. Frank Waters. Dr. J. de Courcy, Ireland, D. Kearns, S. Hooper, Dr. P. C. Denham. A. B. Killeen and S. Shine.[4] The British Association was founded in the same year as Rolt’s Green and Silver was published.

A visit to Clonmacnoise in 1946

When Rolt was planning his canal journey in Ireland he wrote that he knew of no friends in Ireland who could help with the hire of a boat until eventually he made contact with John Beahan of Athlone who had Le Coq, a 28ft x 8ft converted ship’s lifeboat. Rolt found Athlone to be the most river-minded town on the Shannon if not in the whole of southern Ireland. After visiting Galway and Connemara the Grand Canal voyage began at Athlone and moved on to Clonmacnoise. This was ten years before the State began to make improvements to the monastic site to benefit visitors. Rolt recorded of his visit to Clonmacnoise with its line of low hills and eskers:

“After we had some tea we rowed off in the dinghy, landing directly at the foot of the slope that led up to the ruins. As notices informed us, Clonmacnoise is now under the charge of the Irish equivalent of our Board of Works whose care of our historical monuments is usually exemplary. My first impression was that the Irish Board could profit by a study of our example in this respect. [The OPW took more care of the site in the 1950s]. To reach the interior of the churches we had to beat our way through the nettles. As a result of the desire for burial within the precincts, the ruins, including the famous High Cross, were almost submerged beneath a sea of unsightly tombstones of marble of polished granite. [The original crosses are now indoors in the Visitor Centre.] Furthermore, the demand for burial space had quite outrun the limited area available and in consequence the more recent dead displayed no reverence or respect for their predecessors in their anxiety to find room for themselves. Many of the older tombstones had been uprooted and broken by newcomers while newly turned earth was strewn with fragments of human bones. The fact that one’s bones will, in all probability, be uprooted and flung aside by the next generation seems to me to make nonsense of the desire for burial at Clonmacnoise; only the belief that they will lie undisturbed in this quiet place until they rise with St. Ciaran when the last trumpet sounds makes it understandable. It seems to me that the only way of reconciling the dignity of Clonmacnoise with its continued use as a place of burial would be to do three things; firstly, to consecrate additional ground; secondly, for those that desire such memorials, to forbid the erection of unsightly tombstones and to insist instead upon some simple form of recumbent slab; thirdly, to keep the precincts properly mown and tended.

I would add one further point. At one corner of the churchyard we came upon a shack-like wooden structure which we at first took to be a refreshment hut. But instead of a counter for the sale of fizzy lemonade it contained a jerry-built altar. It was, we understood, used on the occasion of organised pilgrimages to Clonmacnoise. What, I wondered, would St. Ciaran make of this latter-day product of the faith which once reared the great High Cross and these tall towers? To remove it would be a more fitting act of piety than a dozen pilgrimages.

From the point of view of the sightseer the most noteworthy features of Clonmacnoise are the aforementioned High Cross, or the Cross of the Scriptures as it is called, to distinguish it from the other crosses within the precincts, and the beautiful doorway and chancel arch of the Nuns Church and a quarter of a mile distant along an old causeway. . . with the possible exception of Glastonbury we have nothing to compare with these ruins in their historical importance. It is for this reason that I have felt moved to speak so strongly about their present state. Clonmacnoise is a monument not of national but of European significance. Long before our great abbeys were thought of, this silent place beside the Shannon was a great seat of learning, culture and Christian faith, a lighthouse of the arts of living in the long night of chaos and barbarism which fell upon Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire, an influence which transcended national boundaries. To-day, when Europe bids fair to fall into a similar state, there are those who believe that it will once again be Ireland’s destiny to become a citadel of Christianity and the humanities. This may well prove to be true, but not until she is more mindful of these monuments of her past greatness, and erects beside them some more worthy symbol of her faith than a wooden shack, for by works are these things judged. . .

The ruined keep of John de Gray’s castle now leans at a drunken angle having been, it is said, blown up by Cromwell. Surely no man in history has, rightly or wrongly, more ruins to his credit; they outnumber by far the beds where Queen Elizabeth reputedly slept or hiding places of fugitive Stuarts. We clambered up the ruined stairs of the castle that evening and sat upon the battlements looking out over the ruins and the river. The wind had fallen completely with the sun, the sky was overcast and it was very still. There was no sound at all but the distant pipe of the curlew crying over the darkening bogs. No landscape can have changed so little in a thousand years. In these days of chaos, arrogance, and confused thinking it is a pity, I thought, that more men cannot contemplate in quietness such immutable solitudes. Their influence is salutory and chastening. They make men aware of his creaturehood, of the brevity of a life ‘bounded by a sleep’, and of the vanity of ambition. But while it thus humbles him, the natural world enlarges man’s humanity by enabling him to perceive the potential greatness of the human spirit with its unique creative capacity. . .

The Danes are reputed to have sailed up the Shannon in their fighting ships to plunder Clonmacnoise just as they came up Severn to sack Worcester. But if this is true how did they ascend these rivers? The fall of the Severn between Worcester and the sea is not very great, but the Shannon falls swiftly 120 feet below Killaloe. Their long boats were surely too heavy to portage. Did they throw temporary dams across the river behind their boats, breaking them down one by one as they returned?

It was nearly dark by the time we rowed back to our boat. Not a breath of wind or eddy of current flawed the surface of the great river; silent it was, and so dark and still that but for the splash of our oars it might have been a sheet of black glass.”[5]

Rolt was refreshingly frank with his comments on Ireland as it clear from his comments on the visits to Clonmacnoise, Clonfert, Banagher, Mullingar and Athlone. We will have more on his Grand Canal trip next week.

[1] V.T.H. Delany and D.R. Delany, The canals of the south of Ireland (Devon, 1966) p. 18.

[2] See biographical details on the University of Bath website.

[3] ODNB, 47, pp 640–41. Entry by R. Angus Buchanan.

[4] See the IWAI website

[5] L.T.C. Rolt, Green and Silver (with photographs by Angela Rolt), (London, 1949), pp 46–50.