The pioneering travel book on the Irish canals was Green and Silver (London, 1949) by L.T.C. Rolt. Tom Rolt made his voyage of discovery by motor cruiser in 1946 along the course of the Grand Canal, the Royal Canal and the Shannon navigation from Boyne to Limerick. The Delanys writing in 1966, considered Rolt’s book to be the most comprehensive dealing with the inland waterways of Ireland. [1] In this extract Banagher gets a severe press very unlike the optimism of the 1890-1914 period and again in the 1960s. Banagher also got a severe jolt post 2008. Things are now improving with sunlit uplands breaking through.

Moving off to Shannon Harbour Rolt got sight of the many arched bridges at Shannon Bridge and passed beneath the swinging span. See last week’s blog by Donal Boland covering the same trip in 2023 as far as Tullamore.

“Just below, was the Grand Canal depot with a canal boat lying alongside the quay. Opposite, and commanding the bridge was a gloomy fortress backed by a defensive wall of formidable proportions which extended westward like a grey comb along the crest of yet another of the green esker ridges. It was a symbol of the more peaceful times that have now come to the Shannon that, according to the signs displayed, part of the fortress had now become a village shop and bar.”[2]

Clonfert

On arrival at Shannon Harbour Rolt and his wife Angela, made a walking tour to the old Clonfert cathedral and to hear more of Brendan the Navigator. They crossed the river and walked along the canal towing path as far as Clonfert bridge. Rolt noted that by 1939 the manual chain ferry boat had been replaced by the steel motor boat. The scarcity of fuel during the war years 1939–45 saw the reintroduction of horse-drawn ferry craft or “emergency boats” to facilitate the transfer of turf. Rolt found the restoration works at Clonfert unsympathetic creating a chilly arid bleakness in the stony interior. He was able to visit the private residence that had been the bishop’s palace and see the yew walk. They returned in poor weather walking into Banagher.[3]

Banagher in 1946: ‘The town seemed to have resigned itself to slow decay’

Rolt noted ‘the usual fortifications stand on the west bank of the river commanding Banagher Bridge. Opposite was the Grand Canal depot and the Maltings which are the town’s staple industry, supplying malt to Guinness’s Brewery at Dublin via the Grand Canal. [This continued at Midland Maltings, Garrycastle until c. 2004. The riverside Waller maltings are derelict and partly demolished.] Behind them, the little town wanders up a gentle slope in a single wide main street. The roadway was ill made, the houses looked seedy and drab, and an occasional derelict property gave the dingy façade of the street a gap-toothed appearance. The town seemed to have resigned itself to slow decay. In short, we thought it the most depressing small town we saw in Ireland. In fairness to the champions of Banagher, however, I should add that this time we were both tired and hungry, that it was raining steadily, and that it was early closing day.

One August day in 1841 a carriage (or more probably a cart or a sidecar) drew up before the hotel in the main street and there descended a shy, rather untidy young man of twenty-six. He had arrived to take up the post of clerk to the distant surveyor, and his name was Anthony Trollope. I hope his first impression was more favourable than mine.[4]

From Shannon Harbour to Tullamore

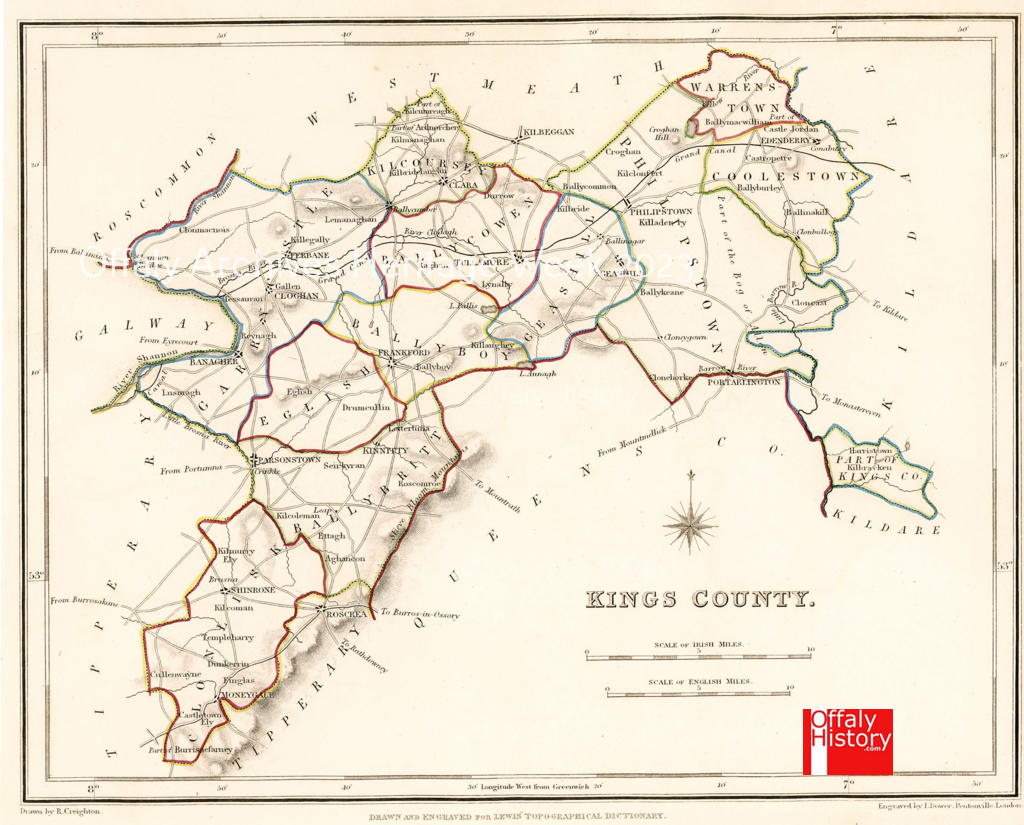

Rolt recorded that the Canal was originally opened for traffic from James’ Street Harbour, and the line from Tullamore to the Shannon was a subsequent extension. Its completion is commemorated by an inscribed stone set in the wall of the first of the two locks leading from the river to Shannon Harbour. Unfortunately, it had so weathered that he could not decipher the lettering. These locks were built with larger chambers than the other locks on the canal to enable the steamers which plied on the Shannon from the 1820s to the First World War to come up into the harbour. It was manifestly only possible for self- propelled craft to navigate the Shannon, so that in the days when traffic through the canal was horse-drawn, goods destined for places on the river were transhipped into streamers at Shannon Harbour. It was this necessity which created the ranges of stone warehouses and the single short street which is Shannon Harbour in the midst of the bleak windswept waste of the Shannon callows.

Since nearby Banagher has its own quay on the river, Shannon Harbour serves no purpose except as a place of transhipment . Consequently when the diesel-engined boats ousted the horse-drawn craft and began to ply direct between Dublin and the Shannon quays, Shannon Harbour suffered eclipse and became little more than a toll office and refuelling point. Yet at the time of the Rolt visit, the original activity was just about to be resumed. For the canal boats were not capable of weathering the violent storms which whip up the Shannon lakes into raging seas. ‘The consequence delays, particularly in winter, are sometimes so great that, in the opinion of the company, they justify the labour of transhipment cargos destined for the Shannon into larger craft capable of making the passage through Loughs Derg or Ree under any conditions of weather. To admit those bigger boats to Shannon Harbour, the two entrance locks from the river were to be still further enlarged in 1946.

When Rolt got through the locks he tied up to the quay at the harbour to pay the toll through to Ringsend Docks, Dublin – about 82 mile distant. The toll was £3 17s. or, in other words, 1s. 9d. per lock for the forty-four locks. Rolt described the old ruined hotel as ‘an enormous stone house of three storeys with a front portico approached by an imposing flight of steps. A semi-derelict tenement, with the steps to the door cracked and broken, this was once an hotel built by the company in the days of the passenger ‘packet’ boat traffic; one of five, the others being at James’ Street harbour, Portobello, Robertstown and Tullamore.’

Rolt noted that passenger traffic once formed a very considerable part of the Grand Canal Company’s revenue. The service was inaugurated on June 9, 1788, when the Lord Lieutenant made a state progress through part of the canal in the new packet boat Buckingham. He took luncheon on board, and was further regaled by the strains of a band of musicians who had installed themselves in a second boat the Mercury. The imagination revels in the contemplation of this wondrous spectacle. Thereafter, the boats plied regularly and traffic increased steadily until, in the year 1837, a total of 100,695 passengers travelled over the canal. For a few years more the figure remained practically constant and them traffic began to fall off. The great famine seriously affected trade; in 1853, passenger traffic ceased entirely, and the coming of railways precluded any revival.

Athy, Tullamore, Shannon Harbour and Ballinasloe were the most important stages, and boats left Dublin for these destinations in the morning and afternoon from James’ Street Harbour and from Portobello. There was first- and second-class accommodation, First-class passengers being allowed eighty-four pounds of luggage and second-class forty-two pounds. First-class fare from Dublin to Tullamore was 9s. 2d., and second-class 4s. 9d. ‘Second-class’ was the equivalent of ‘outside’ travel on a stage coach, although it is said that they had the advantage of a roof over their heads. Engravings of the period, however, would appear to suggest that they merely sat on the open cabin roof in imminent peril of having their heads knocked off when passing under bridges.

The traffic was certainly organised on precisely similar lines to the stage coaches and the company’s hotels were simply the posting houses of this water-road. Like the stage coaches, the ‘express’ of the water were the narrow ‘fly’ passage boats by which the first- and second-class passengers travelled [from 1834]. By means of four horses travelling at the gallop, and by frequent changes, they managed to average eight miles per hour including the passage of locks. They travelled only by day. No doubt in winter the morning boat from Dublin rested at Tullamore, and the afternoon boat at Robertstown, meanwhile the impecunious travelled in the equivalent of the road wagon, a slower and heavier craft which carried which carried parcels as well as passengers and which travelled night and day.

In those days there was considerable interchange of passenger as well as goods traffic at Shannon Harbour. Travellers changed here from the Dublin passage boats into Bianconi’s ‘long cars’ which operated between Birr, Shannon Harbour and Athlone in connection with the boats. Alternatively they might board the paddle streamers The Lady Lansdowne or The Lady Burgoyne which plied between Killaloe pier head and Athlone, calling at a jetty on the river near the mouth of the canal. Smaller craft sailed from Killaloe pier head to the transatlantic port of Limerick, and so the Grand Canal became a link in the route between Dublin and America. Shannon Harbour became celebrated for its oaten bread which passengers purchased in large quantities to take with them on their long voyage across the Atlantic. The departure of a passage boat from Shannon Harbour was heralded by the ringing of a large bell in the now empty cote over the stables. This was tolled three times, once for the horses to be harnessed, twice for the passengers to board, and thirdly as a signal for departure.

Shannon Harbour

To-day, Rolt reminds us, all that remains to tell of this once extensive traffic, apart from the gaunt hotels, are the early records and a few relics, such as an old menu card of a blunderbuss once carried by a postillion, which are preserved at the offices of the company. Yet the passage boats have left their mark in contemporary literature. Charles Lever in his novel Jack Hinton sends his hero on a passage boat from Portobello to Shannon Harbour where he attempts to find accommodation at the hotel, then already in decay. Rolt say he was fortunate in possessing a copy of this forgotten novel. But confined himself to citing a brief passage depicting the arrival at Shannon Harbour. Lever’s character describes his arrival at Shannon Harbour:

‘…the sedgy banks whose tall flaggers bow their heads beneath the ripple that eddies from the bow…the loud bray of the horn…the far-off tinkle of a bell. We near Shannon Harbour, and all its bustle and excitement. The large bell at the stern of the boat is thundering away…the banks are crowded…the track rope is cast off, the weary posters trot away to their stables, and the stately barge floats on to its destined haven without the aid of any visible influence. A prospect more bleak, more desolate, more barren it would be impossible to conceive – a wide river with low and reedy banks, moving sluggishly on its yellow current between broad tracks of bog or callow meadow-land; no trace of cultivation, not even a tree to be seen. Such is Shannon Harbour.’

[1] V.T.H. Delany and D.R. Delany, The canals of the south of Ireland (Devon, 1966) p. 18.

[2] Rolt, Green and Silver, pp 51–2.

[3] Ibid., 57–9.

[4] Ibid., p. 59.