We looked a few days ago at Charles Lever’s description of Shannon Harbour through the eyes of Jack Hinton (1843) and which he commenced writing in the winter of 1841. Another visitor to Banagher was the celebrated novelist, Anthony Trollope. Material has already been published on Offaly History blog on Trollope’s connection with Banagher where he arrived in September 1841 to take up employment with the Post Office. In his Kellys and the O’Kellys (London, 1848), Trollope sends Martin Kelly from Portobello, Dublin to Ballinasloe. His description of the journey is as derogatory as Lever’s and may well be autobiographical as Trollope travelled on the canal as a young man to take up that first post at Banagher.

Mr Kelly, Trollope tells us, travelled continuously for twenty hours, arriving at Ballinasloe at 10 a.m. whence he caught a Bianconi car to Tuam. He complains of the tedium of canal travel:

‘Reading is out of the question. I have tried it myself and seen others try it, but in vain. The sense of the motion, almost imperceptible but still perceptible; the noises above you; the smells around you; the diversified crowd of which you are a part; at one moment the heat this crowd creates; at the next the draught which a window just opened behind your ears lets in on you; the fumes of punch; the snores of the man under the table: the noisy anger of his neighbour who reviles the attendant sylph; the would-be witticisms of a third, who makes continual amorous overtures to the same over-tasked damsel, notwithstanding the publicity of his situation; the loud complaint of the old lady near the door, who cannot obtain the gratuitous kindness of a glass of water; and the baby-soothing lullabies of the one, who is suckling her infant under your elbow. These things alike prevent one from reading, sleeping or thinking. All one can do is wait till the long night gradually wears itself away, and reflect that, Time and the hour run through the longest day… I believe the misery of the canal-boat chiefly consists in a preconceived and erroneous idea of its capabilities. One prepares oneself for occupation – an attempt is made to achieve actual comfort – and both end in disappointment; the limbs become weary with endeavouring to fix themselves in a position of repose, and the mind fatigued more by the search after, than the want of, occupation.

Trollope’s opinion of Grand Canal Company’s catering abilities also appears to have been low: ‘He [Martin Kelly] made great play at the eternal half-boiled leg of mutton, floating in a bloody sea of grease and gravy, which always comes on the table three hours after the departure from Porto Bello. He, and others equally gifted with the dura ilia messorum, swallowed huge collops of the raw animal, and vast heaps of yellow turnips, till the pity with which a stranger would at first be inclined to contemplate the consumer of such unsavoury food, is transferred to the victim who has to provide the meal at two shillings a head. Neither love nor drink – and Martin had, on the previous day, been troubled with both – had affected his appetite; and he ate out his money with the true preserving prudence of a Connaught man, who firmly determines not to be done.’

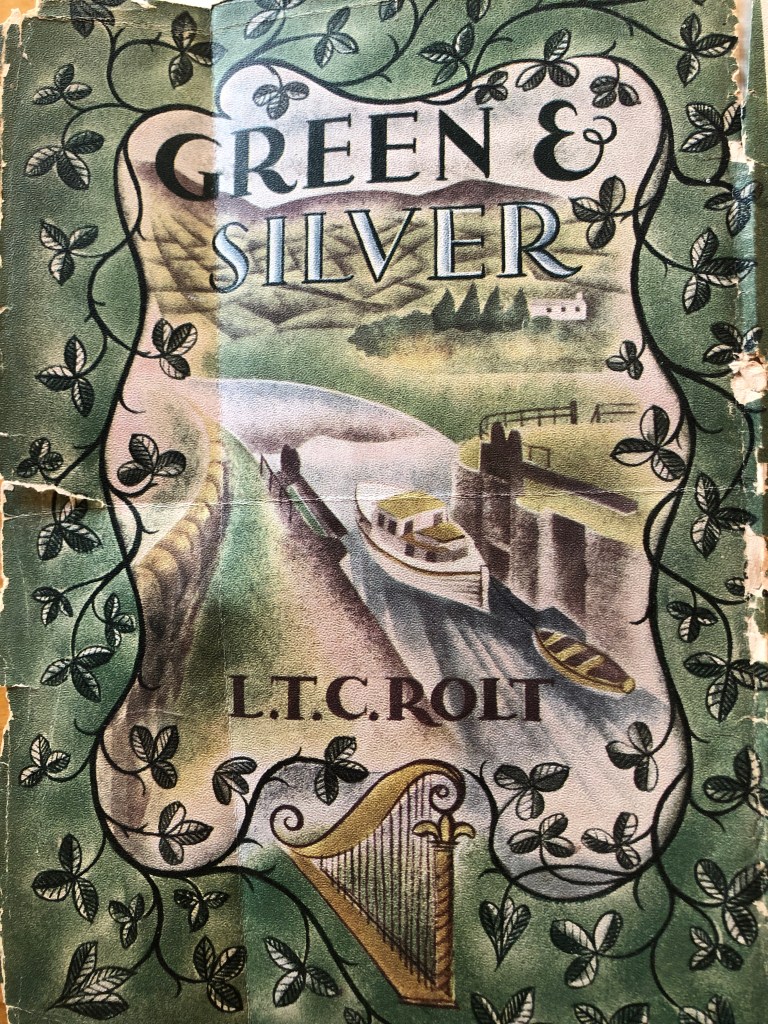

Rolt in Green and Silver (London, 1949) reproduces an extract from an account of James Johnson, M.D., in his A Tour in Ireland (1844), which describes a departure from Portobello in less disparaging and more informative terms:

‘At Portobello… the head of the Grand Canal… there was bustle enough. Passengers of all descriptions with their diversified luggage were tumbling into the fly-boat on the quay. This same boat is curiously constructed, and a very slight inspection of it would prove its Hibernian origin. In all other boats – even canal boats – in England, the best cabin is in the stern; but here it is on, not under, the forecastle. The Captain’s cabin is amidships and the cabin of the crew, with caboose and all kinds of stinkables and filth, is in the stern. The cabin of the passengers, although rather small, is far from uncomfortable, and in fine weather you may sit outside on the small forecastle or platform. When passing the locks, however, which are numerous, or rather, innumerable, all hands are crammed into the cabin, and the door is closed to prevent the spray coming in, while a regular cascade tumbles headlong down close to the head of the boat and splashing over the forecastle.

‘The horses were put to, and away they went at full gallop exactly at 7 o’clock. But the locks in the first ten or fifteen miles are very numerous, though it must be confessed they passed through them with wonderful rapidity. They will get through a double lock even on the ascent in five minutes, and on the descent to the Shannon in three minutes or less. [The summit level is at the 18th lock and 279 ft. and near Robertstown.] The dress of the postilions, the measured canter or gallop of the horses, the vibration of the rope, the swell that precedes the boat, and the dexterity with which the men and horses dive under the arches of the bridges without for a moment slackening their pace, all produce a very curious and picturesque scene such as I have never seen equalled in Holland or any of its canals.’

Ruth Delany wondered if things were as bad as Lever and Trollope suggested. She cites an 1862 description of the interior of a passage boat by someone who was travelling to Galway by train in 1862 and thinking aback to the canal journey (from her book, The Grand Canal of Ireland).

‘The cabin was a long, narrow apartment, along either side of which ran a bench covered with red moreen, and hard enough to have been stuffed with paving stones, but I believe it was really with chopped hay, and capable of accommodating on each seat fifteen uncrinolined individuals, who might sit there comfortably enough on a cold winter’s day, with a roaring turf fire in the small grate, as I have done more than once, while the boat was being slowly forced through a sheet of ice, several inches in thickness… Well, between the seats ran a narrow table of about a foot-and-a-half in width, which was now covered with the small parcels of the passengers – books, boxes, baskets, dressing cases, and oh, horror! A cage containing a fine singing canary.’

Another more recent account is that of Raymond Gardner Land of Time Enough (London, 1977) which is not by any means as useful as Rolt but is of interest for contemporary printed detail such as the reference to the former canal company engineer at Tullamore, the late John McNamara and the late Walter Mitchell, ‘one of the grand old men’ of the canal. ‘Walter came from a long line of canal families, the longest line since he could boast that a Mitchell has been connected with the waterway since its inception and that the records show an overseer named Mitchell employed during the construction. Gardner tells us that the family is Scottish, Protestant and Republican which is as many apparently irreconcilable antecedents as you are likely to find in Ireland. Walter worked in his cousin’s drapery in Tullamore when he was a lad but in the early [nineteen] thirties he came back to live in his father’s lock house and eventually took over. He cannot remember the precise date he started but he’s been more than forty years at Rahan lock and depot and, now seventy-five, looks as though he’ll be there for another forty.’ He told Gardner that

‘In the old days Rahan was a staging post where horses were changed. You can still see the remains of the stables and the out-houses where the horse drivers could rest overnight. But sometimes it was a bit hard to tell night from day for when the Guinness boats were working twenty-four hour shifts they would arrive here at two-thirty or three-thirty a.m. and I’d have to be out of bed and working them through. There wasn’t a light to be seen. The boatmen didn’t like lights on the boats as they found it easier to adjust to the gloom, than be blinded by another craft approaching with a searchlight on the bows. There’s a nice one I heard somewhere about one of us keepers who was asked by a gent from Dublin how many years he had worked for the company. Your man said a hundred years and when the Dublin man asked how he arrived at the figure he got told that it reckoned out at fifty years by day and fifty years by night. Mind you at that time the pay was pitiful and the country lock-keepers were paid even less than those in the towns. By God, we were the poorest of the poor. So most of us had another job here and there. I did a bit of farming and I still keep a few cows on a parcel of land since I like to have my own milk and none of that bottled stuff.

‘There have been some queer events at Rahan. We were always having inspectors and engineers arriving to look for possible damage and, of course, they’d always know better than any Tom, Dick or Walter of a lock-keeper. I remember that the dredger arrived just below the lock and though I warned the boys that they were cutting too deep, they would have nothing of it. Next morning there was a bloody great lake in a hollow just a few hundred yards from the canal and not enough to wash your big toe with along the line. But the tale I like best is of the famous local well which everyone swore by. It came out near a spot where the farmer swam his cattle from bank to bank. You’ll know just what happened. Along came CIE to repair the trampled bank and lay a concrete underwater channel down the sides of the embankment to halt the erosion. Next day the damned well was dry. And that was the end of Rahan’s legendary spring, not that everyone cares to remember the legend.’ Time was when no farmer would have allowed his animals to stray along the line for the old Canal Company offered a reward to lock-keepers for every pig destroyed found grubbing there. Unlike the canal companies in England who often only had rights to the cut and the towpath, the Irish promoters owned strips of land on either side of the cut. Under nationalisation these passed into the hand of CIE. But before that time, when revenue dwindled, the canal company let portions of this land to farmers and even stretches of the line had grazing rights attached. This policy has been stopped as rights to grazing come up for renewal. Nevertheless some farmers are obliged to swim their cattle across since the Grand was built with very few accommodation bridges.’

Gardner later visited The Thatch in Rahan and also Tullamore where he described John McNamara’s office in the harbour as a high point of the trip because of its historical collection of photographs and maps.

Gardner subsequently described meeting Michael and Heather Thomas [now both deceased], who had done so much to promote the Grand Canal through Celtic Cruisers – their hire line of boats in the style of the old fly boats.