This evocative piece of writing, describing childhood in Shannon Harbour in the 1950s by Gerry Devery, Cuba Avenue, Banagher won for him the prestigious 1st prize, Autobiographical section in the Writers’ Week, Listowel, Co. Kerry in May 1991. It is one of my many interesting articles over the years in the Banagher Review.[1] Our thanks to Gerry Devery for permission to publish this stylish piece on the terminus of the Grand Canal in County Offaly

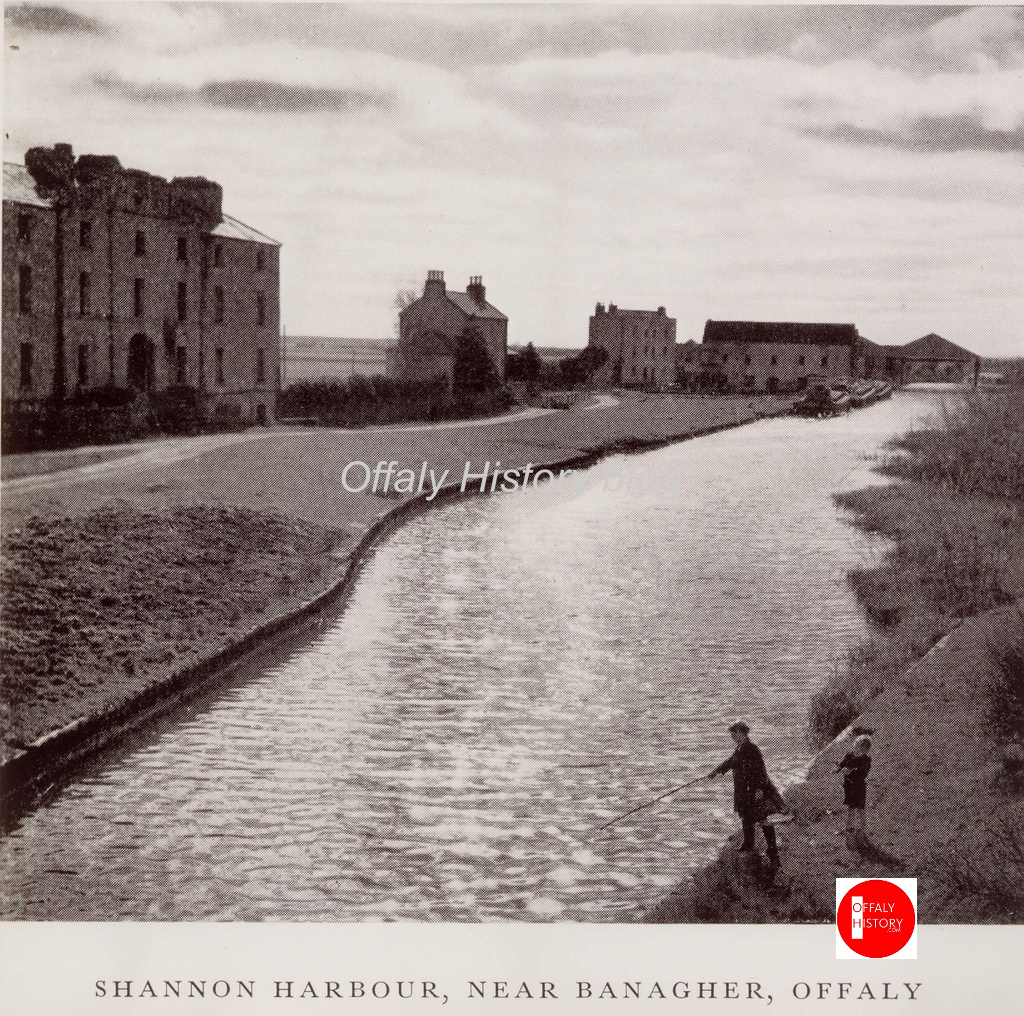

Where the murky, still waters of the Grand Canal join the majestic River Shannon in the heart of the midlands, lies a small village; Shannon Harbour. Here I was born. This once vibrant and prosperous little place, is now quiet and silent with only a few inhabitants and its ghostly ruins to betray its past.

I spent the first fifteen years of my life, in an enormous old house, right by the edge of the canal. My memories of those times, when all life revolved around the village and the canal are very fond ones, it was the beginning of the fifties then and although life was pretty hard for my parents, neither I nor my three brothers and sisters realised this until much later in life. Looking back now I can understand what a difficult job it was to rear seven children within a few feet of the canal bank.

Our house was a huge, old three-storey mansion which had once been an R.I.C. Barracks. It was a cold, bleak place with large windows and a high wall surrounding it. We had no electricity; an oil lamp gave us light. We drew our water from the communal pump in the centre of the village, carrying it home in large enamel buckets. My father, being an employee of the Grand Canal Company, had rented the house, from his company. Although we hadn’t any of the modem day comforts, we were happy enough. My mother was always busy cooking and washing. Trying to keep track of the seven of us was a full-time job in itself. Because the canal was so close there was always panic when one of us went missing, even though we could all swim. We learned to swim as soon as we learned to walk. Swimming was second nature to us.

Each winter and summer held its own special delights. Sometimes in winter the riverbanks burst and the area became a gigantic lake. When the nights were long and dark we fell asleep to the lonesome calls of the wild swans and geese and when the hard frost came it was a winter wonderland. The thick ice on the canal was as hard as the frost beside it; the canal boats motionless in its frozen eternity.

Christmas was the highlight of the year for me. About the middle of November all the villagers would come together to round up the geese. These geese had once been domesticated but over the years they had taken to the waters and become half-wild.

Most of the scrawny fowl were captured in the round up. Some of the householders used the geese for gambling purposes. “Goose Card Night” was a great occasion in our house. All day long, mother was busy making buns and sandwiches.

Between eight and nine o’clock the boatmen and the other card players from the village filed in until our kitchen was full. I used to stand by the fire watching the solemn faces of the players as the cards were dealt. I remained there until lady luck decided who was to take home the first scruffy goose. Every now and then the silence was shattered by a thump on the wooden table as a player placed a card and shouted triumphantly “that’s game!” I always waited impatiently for break time. Mother, and my older sisters made the tea and the ham and corned-beef sandwiches. They were a rarity in those days and were devoured by one and all before the final session of cards began. Those card nights were a big social occasion for the people of the village and the surrounding area. They meant that my mother had an extra few pounds for Christmas. The summers of my childhood seemed never-ending and beautiful. After the long hard winter the countryside was so fresh and alive. The canal was at its busiest then. Daily, the boats ploughed the smooth waters, toing and froing with their cargoes.

Right in front of our house stood the large warehouse of the Grand Canal Company. It was there that my father worked for the greatest part of his life, loading and unloading the cargoes with a small crane suspended from the ceiling. Sometimes I sneaked in there to watch the boatmen at work and to gaze admiringly up at my father in his cramped little box while he moved backwards and forwards with each load. How I envied him and longed for the day when I would be big enough to work his exciting crane.

When the summer holidays came the long hot days were for me filled with adventure and expectation. Each morning I woke early to the staccato sound of a canal barge in the distance. I dressed quickly and raced up to the bridge to meet it. Slowly the barge came into view, its pilot standing erect and watchful at the rudder. It passed under the narrow bridge, its blunt hull parting the calm, glassy waters and pounding them off the rushy banks. Then it chugged its way into the harbour with its cargoes of corn, cement, all sorts of hardware and its kegs of ale and Guinness. The pungent smell of diesel filled the air as it came to a stop. Another day in my life by the canal had begun.

Those boatmen were a special breed of men. They took great pride in their work and always seemed cheerful and contented. They were large, hardy fellows with weather beaten faces. Many of them owned arms as big as tree trunks and bulging bellies with thick leather belts slung around them. They spent most of their lives in their boats. Each boat was a home and every boatman had a story to tell about life on the canal.

“Big Ned”, as he was known to everyone on the barge was my special friend. I always waited eagerly for his boat to arrive. Ned was an enormous man with a long white beard and bushy eyebrows. He was as strong as an ox, yet gentle as a giant. He was never without his black peaked cap and he puffed a long, crooked pipe continuously.

I was always invited on to the boat. This was a great treat. The living quarters, where the crew of four or five ate and slept, I thought cosy and inviting. If there was one thing a boatman liked better than his pint it was his food. I remember, as if it was yesterday, sitting in the cabin watching Ned preparing the evening meal. This was more of a small feast. Ned unwrapped huge pieces of steak from brown paper and placed them to sizzle on the frying pan with a mound of onions and fresh mushrooms. When all was ready I was given my plateful. Proudly I went up on deck with my delicious meal. Ned brought with him my mug of strong tea. One mug of tea followed another. When the eating was done Ned lit his pipe, stroked his beard and began telling me his wonderful stories.

I was fascinated and didn’t care if they were true or not. He told of the canal ghosts that he had seen and of the crewless boats that moved quietly down the canal at night He made the hairs stand on my tiny neck. Ned showed me how they extracted a few pints of porter from the wooden kegs without breaking the seal. He called it “taping the barrel”. The metal hoop around the middle of the barrel was moved a couple of inches.

A small hole was drilled through the wood. When the frothy black stuff had poured into the bucket a wooden peg was wedged into the hole. The metal hoop was then beaten back into place. The boatmen had their free supply of drink and nobody was any the wiser. One day Ned looked drawn and worried. Standing beside him on deck I sensed something was wrong. He gazed into the distance; he spoke softly of change and progress. His pipe went out. He didn’t bother to relight it but bent to tell me that the days of the Grand Canal were numbered. The future, he said, lay in the railways and the roads. Lorry drivers and train drivers would do the work of the boatmen.

“But they can’t kill the canal! They can’t kill you either, Ned. I won’t let them!” I shouted.

Ned placed his broad arms around me and whispered, “What will be, will be, my little friend”.

I became a man at eight years of age, trying to stand and talk, to hold back my tears. Three weeks later the canal was closed. I never saw Ned again, but my gentle giant still lives in my mind.

Every now and then I return to visit Shannon Harbour. When l stand on the little bridge and look at the gaunt shell of our old house I see a bereaved mother. She is watching over the dead canal. Yes! I long to be a child again.

[1] Thanks to Jim Madden and others Offaly History has almost a full set of this parish magazine published from the 1980s up to recent years. Also published in the Midland Tribune, 9 Jan. 1993.

Our thanks to Gerry Devery for this article and to James Scully for his help. Also to the Tullamore Tribune. Pics and captions Offaly History save as stated.