Patrick Lynch and John Vaizey in their history of Guinness’s brewery in the Irish economy to 1876 observed that in England the canals followed trade while in Ireland it was hoped that trade would follow the canals. It was a hope that was only partially fulfilled as outside of Dublin the new canals served few areas of commercial or industrial importance.[1] The observation was following in the line of Arthur Young in the 1770s who had advised ‘to have something to carry before you seek the means of carriage’.[2] Yet the record of the carriage of goods on the canal was satisfactory with 500 million ton miles carried in 1800 and double that by the 1830s.[3] The Grand Canal was especially beneficial to north Offaly for the transport of stone, brick, turf, barley, malt and whiskey. All bulky goods suited to water transport. The emerging firm of Guinness also found the inland water transport system helpful to sales and market penetration. The slow movement of Guinness beer by waterway was good for product quality on arrival.

Work on the Grand Canal started in 1756 and by 1779 the first stretch of water from James’s Street to Robertstown was completed. Over the next twenty years the canal was extended to Tullamore (1798) and Shannon Harbour (1804). The six-year delay at Tullamore while resolving issues with the direction of the ‘Brosna Line’ at Tullamore facilitated the establishment of a canal hotel, stores and a harbour.

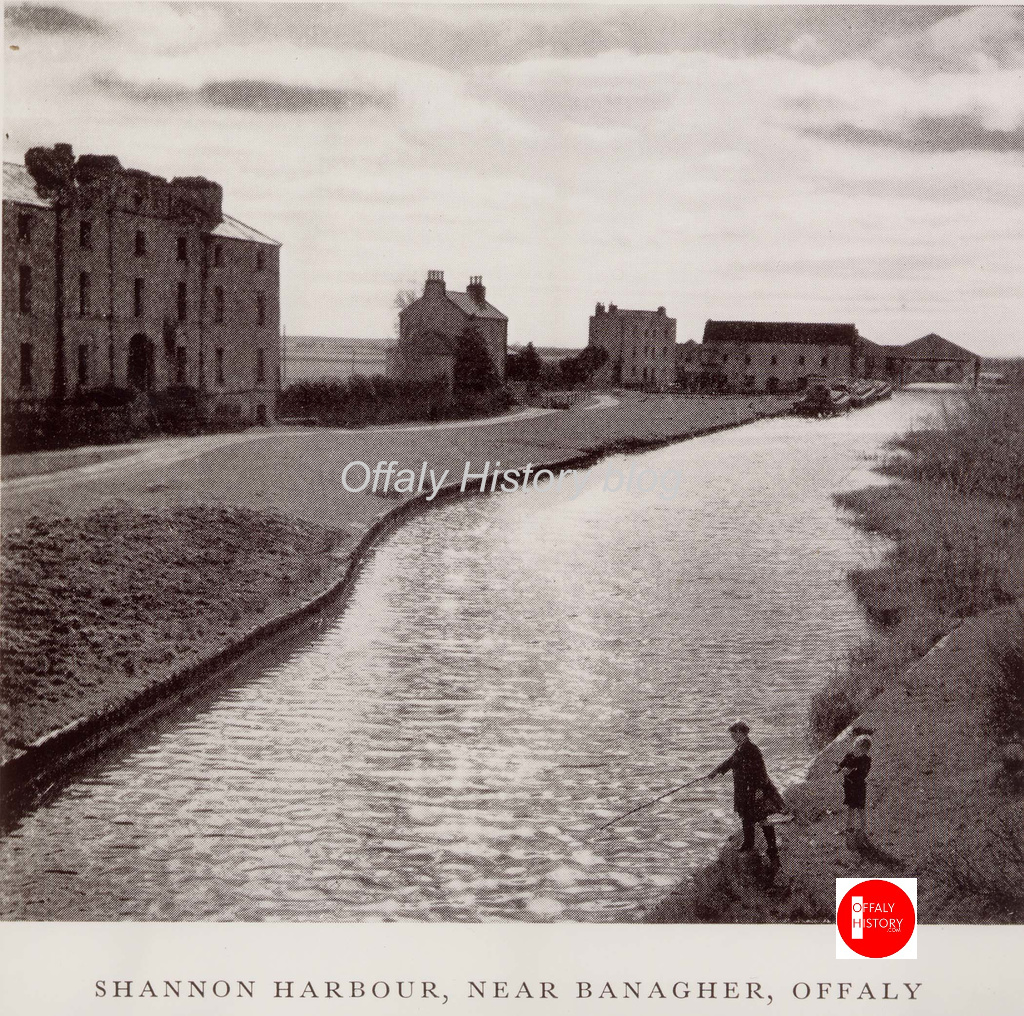

Until 1850 the Grand Canal Company was not allowed to carry commercial traffic and this was left in the hands of agents. The company concentrated on the passenger traffic trade while providing the stores on the canal network for rent to traders and boatmen. Lynch and Vaizey make the point that Shannon Harbour, the terminus of the Grand Canal from 1804, became a great distribution centre, especially with the opening of the line to Ballinasloe in 1827.[4] The value of the new means of communication was clear as early as 1798 by which time Guinness had developed a commercial trade with Athy, forty miles from the city of Dublin and on the Grand Canal line. The brewing industry had also been helped by the beneficial legislation of 1795.[5] While the industry suffered due to Fr Mathew’s temperance campaign the switch from distilled whiskey to beer was already in full swing.

The increased trade in beer, corn, malt, stone, brick and turf is evident from the number of commercial carriers on the canals after 1800. Francis Berry (d. 1864) of Tullamore and Thomas Berry of Shannon Harbour were among those carrying for Guinness. In 1807 out of a total production of 20,000 hogsheads (for Guinness this was 52 gallons and for others 54) 5,000 hogsheads (two million pints) were being sent via Shannon Harbour for sale further west. [6]. Robert Berry of Eglish and Shannon Harbour was a brother of Francis Berry and both brothers were connected with the business. Robert died in 1822 and Francis in 1864. Robert was probably related to the Thomas Berry of Stradbally who gave evidence to a parliamentary committee in 1857 blaming the railways for the loss of the carrier business (KCC, 17 June 1857).

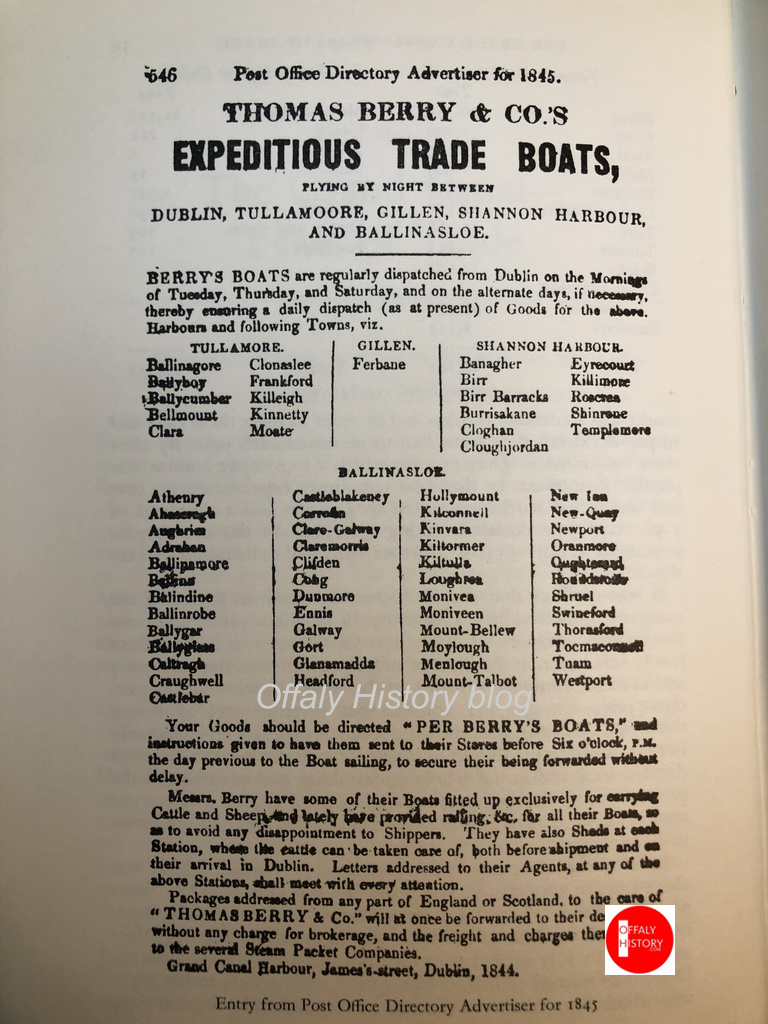

According to Delany the principal traders on the canal were Hyland, Pim, Duggan and Berry, and on the Shannon Palmer, Going, Dillon and Glynn. Berrys commenced trading in 1806 and soon leased stores at James’s Street, Tullamore and Shannon Harbour. The care taken in the matter of handling farm animals (see image of 1845 below) was evident in a memorial of 1829. Berrys stated they had conducted their business in a more spirited manner than other traders and ‘had introduced hatching, locking and sealing of boats, weighing and examining goods on receipt and delivery, taking samples out of spirits and measuring the depth of casks. A resident partner looked after the business at each of the three centres and all their employees were of good character.’ Furthermore they had extended their trade into the coutnry by introducing ‘scotchdrays and large spokewheel carts’[1] Ruth Delany, The Grand Canal of Ireland (Dublin, 1973, 1995), p. 71.

Francis and Sterling Berry are listed in the 1824 Pigot Trade Directory entry for Tullamore as boat proprietors. They are also listed for the Pigot Grand Canal entry under Dublin, for Dublin to Shannon Harbour three days per week and ditto from Shannon Harbour to Dublin. Their main competitor was Hyland & Sons.

In 1807 out of a total production of 20,000 hogsheads (for Guinness this was 52 gallons per hgd and for others 54) 5,000 hogsheads (two million pints) were being sent via Shannon Harbour for sale further west. [2]. Delany, The Grand Canal, p. 123. The stores at Shannon Harbour were at one stage owned by Pim’s. The Guinness family were protective of their growing business and knew that to keep ahead their product had to be good and to be cheap. A low price would deter other competitors from entering the market, and so Francis Berry was advised by the Guinness firm in 1829.[3, Delany, Grand Canal, p. 79.] Berry was agent to Lord Charleville of Tullamore who had been a director of the Grand Canal Company in the 1790s and continued to represent Charleville and his family until Bery’s death in 1864. Berrys sold their carrier business and ten boats to the Grand Canal Company in 1850 – a time when the railways were growing in popularity for passenger traffic and for goods traffic.[4, V.T.H. and D.R. Delany, The canals of the south of Ireland (Devon, 1966), p. 69; Ruth Delany, The Grand Canal of Ireland (Dublin, 1973, 1995), p. 69.] The railway reached Tullamore from Portarlington in 1854 and was connected with Athlone and Galway by 1859. Not surprisingly Shannon Harbour and Ballinasloe had declined in importance by 1850.[5, Delany, Grand Canal, p. 147] For passenger traffic the decline began by the 1830s with the improvements to the coaching services of Bianconi and others. The fly boats in use from 1834 had helped beat off the competition from Bianconi but could not overcome the railways save in the context of heavy goods excluding livestock which better suit the railways and helped promote the fairs in towns served by rail

.

The Guinness family were protective of their growing business and knew that to keep ahead their product had to be good and to be cheap. A low price would deter other competitors from entering the market, and so Francis Berry was advised by the Guinness firm in 1829.[7] Berry was also agent to Lord Charleville of Tullamore who had been a director of the Grand Canal Company in the 1790s and continued to represent Charleville and his family until Berry’s death in 1864. Robert Berry & Co sold their carrier business to the Grand Canal Company in 1850 – a time when the railways were growing in popularity for passenger traffic and for goods traffic. The railway reached Tullamore from Portarlington in 1854 and was connected with Athlone and Galway by 1859. Not surprisingly Shannon Harbour and Ballinasloe had declined in importance by 1850.[8] For passenger traffic the decline began by the 1830s with the improvements to the coaching services of Bianconi and others. The fly boats in use from 1834 had helped beat off the competition from Bianconi but could not overcome the railways save in the context of heavy goods excluding livestock which better suit the railways and helped promote the fairs in towns served by rail. Tullamore being a prime example with 12 fairs each year by the 1890s.

The growth in the sales of Guinness after 1850 was phenomenal. Guinness’s Irish country trade rose from 17,000 hogsheads in 1855 (or 21 % of the total sales of Guinness) to 230,000 hogsheads in 1880 (or about 40% of the total trade. While the greater part was porter 102,000 hogsheads was Double Stout – the more expensive of the two beers. By 1860 over half of the beer sold outside Dublin was Guinness.[9]

Locally the firm of Deverell controlled the Tullamore brewery and disposed of it to the Egan family in 1866. Egans expanded the business in the 1880s and it survived until the 1920s – the only brewery in County Offaly. That of Woods in Birr had closed by 1880 and became the Birr Malting Co, later Williams at Castle Street, and from 1974 Williams Waller. The breweries of the 1830s evident from the ordnance maps of King’s Co at Shinrone, Birr and elsewhere had long gone.

Berry’s trade was taken over by the Grand Canal Company itself in 1850, because an Act of Parliament in 1845 had allowed the company to act as a commercial carrier , in order to meet competition from the railways.[10] Berrys had to leave the carrier markert and their main client the Guinness firm was also concerned as to who they would now be dealing with and wrote to the Canal Company on 27 December 1850:

The Directors of the Grand Canal Co.

Gentlemen,

We would respectfully take leave to ask, as you, we learn, have purchased the interest of our friends and Agents the Messrs Berry on your hire, how our business is in future to be conducted? As the most considerable Shippers by their Boats we should wish to know who are the parties to whom we are in future to be connected with? Who are to be responsible to us for our consignments, as they were not alone our Carriers but our valued Agents?

Allow us to say that the present proprietor of their concern, his father, and other Members of his family, have been closely connected with us in the way of business, between 30 and 40 years, and having been conducted by them with ability and success, we hope that we may still have the connexion carried on, and we trust Your arrangements may be made to correspond with our wish and interest. We are quite satisfied that what is right you will do, but felt it due to Messrs Berry to express our hope that we may still have the advantage of their excellent services.

- Guinness, Son & Co.[12]

After Berry’s closed in 1850-51 the new agents in the midlands were Patrick Rourke (Berry’s former clerk) at Athlone and Ballinasloe. Ballinasloe was a busy depot for Rourke and Guinness. Rourke was allowed 5% on all sales, the rent of the stores and travelling expenses. Rourke it was said was a good salesman but not a good businessman and died in 1861 owing Guinness brewery £5,000. There was also a new sub-agency at Birr which sold 1,500 barrels of Guinness in 1859. Rourke was followed by his son John (died 1864) and Thomas Hogan (an uncle). At this time the country trade in Ireland was worth a third in money terms of Guinness’ total sales.[13] Rai, now come to the fore, would have been a benefit to Portarlington, Tullamore and Clara. It also encouraged direct sales to wholesalers and publicans with more by-passing of agents.

Lynch and Vaizey note that Shannon Harbour was also losing its place in the sales hierarchy. The growing city of Limerick went ahead of Shannon Harbour and Ballinasloe as distribution centres. Belfast and Cork, both with access by rail, ranked after Limerick, followed by Galway, Ballinasloe and Shannon Harbour. Guinness brewery sales reached £1m in 1872 and of this £0.45 m. was in England, £0.25 m. in Dublin and the balance of £0.3 m. in the rest of the country.[14]

Guinness was growing its market share in the 1870s and such was its share of the market that it was buying over half of the Irish barley crop. Much of this went direct to the brewery to be malted but the independent maltsters in Rathangan and Tullamore also sold to Guinness. Lynch and Vaizey cite Mountmellick in 1878 where Guinness bought 43,000 barrels of malt from Sheare, 15,000 from White, 33,000 from Carter’s at prices varying between 2s. 6d. and 3s. for the malting operation. In all that year the brewery bought 203,000 barrels of malt at a total cost of £349,000. ‘Of the average price per barrel of 34s. 4d., 21s. 4 3/4d was for barley, 10s. 7d. excise duty and about 2s. 4 1/4d was the cost of malting. Prices paid to maltsters varied and the usual price in the 1860-76 period was 32s. to 35s. per barrel.[15]

When the Egan brothers acquired the Tullamore brewery of Deverell’s in 1866 the sale of Guinness nationally was 322,477 bulk barrels of 36 gallons. In ten years this had more than doubled to 777, 597 bulk barrels.[16] Such was the challenge for any local brewer. Nonetheless Egan’s expanded their Tullamore brewery in the mid-1880s and also their malt trade with Guinness. Suffice it to say that the carriage of grain, malt, porter and empties constituted 50% of the Grand Canal Company business in 1912 and over 40% in 1956. In 1912 the carriage of porter on the canal amounted to 37,568 tons and this was down to 21,259 tons in 1956.[17]

One news article in 1883 noted that the Egan brewery was turning out ‘from thirty to forty barrels of ale and porter per day, which is disposed of in the surrounding towns. The Corn Stores, three in number, attached to the brewery are capable of containing 15,000 barrels of grain, and in the splendid malting houses, also attached, upwards of 8,000 barrels of malt are made during the season. The brewery affords considerable employment, the wages expended, on labour alone amounting to nearly 1,500 pounds per annum.’[18]

The Egan brothers were more into bottling than brewing and the brewery department, concentrating on ales, closed in the mid-1920s. The Perry brewery at Rathdowney, Laois survived until the mid-1960s when taken over by Guinness.

From the Tullamore Tribune in the 1990s

[1] Patrick Lynch and John Vaizey, Guinness’s brewery in the Irish economy, 1759–1876 (Cambridge, 1960).

[2] Cited in Cormac ó Grada, Ireland: a new economic history, 1780–1939 (Oxford, 1994), p. 137.

[3] Ibid., pp 135–6.

[4] Ibid., p. 23.

[5] Ibid. pp 68, 74.

[6] Ibid., p. 123.

[7] Ibid., p. 79.

[8] Ibid., p. 147.

[9] Ibid., 201.

[10] Ibid., p. 204.

[11] V.T.H. and D.R. Delany, The canals of the south of Ireland (Devon, 1966), p. 69.

[12] Lynch and Vaizey, ‘Gunness’s brewery’, p. 204.

[13] Ibid., 209–11

[14] Ibid., 211.

[15] Ibid., p. 222.

[16] Ibid., p. 260.; see also Maurice Egan’s two published books and blogs in this series.

[17] V.T.H. and D.R. Delany, The canals of the south of Ireland (Devon, 1966), pp 75–6.

[18] The King’s County: epitome of its history and topography (Midland Tribune, 1883), p. 14.

[19] Lynch and Vaizey, ‘Gunness’s brewery’, p. 204.