Nineteenth-century Edenderry experienced a prolonged building programme, spearheaded by successive members of the Hill family, marquess’ of Downshire. Chief amongst these was the building of a branch line of the Grand Canal to Edenderry in 1802, furthering the line which had passed within two kilometres of the town in 1796. This line brought extensive investment to the area and was the catalyst for the building of stone and slated houses which replaced cottages and cabins.

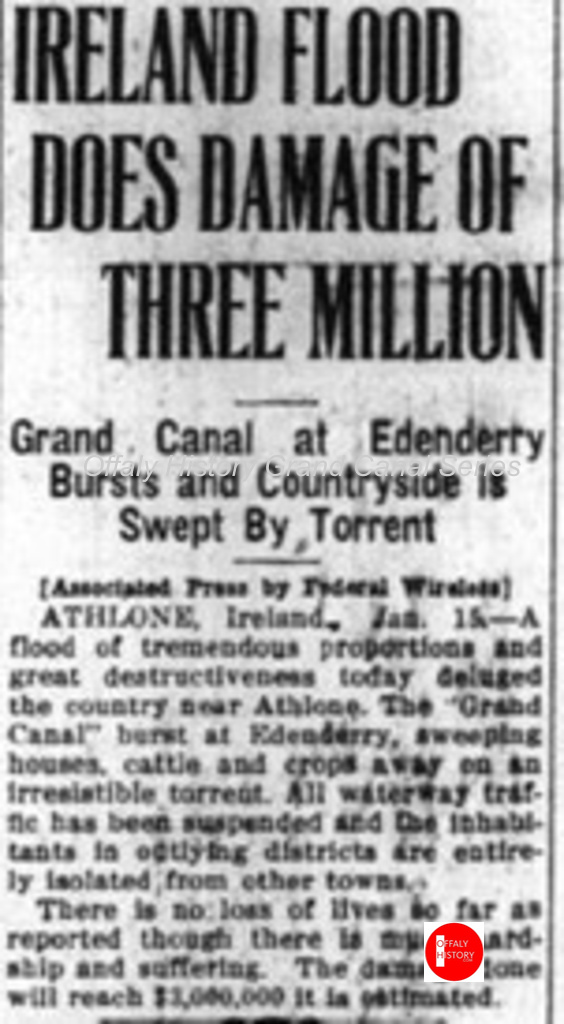

However, the local economy of Edenderry could be severely hampered by damage to the canal system. In January 1916, for example, the canal burst its banks for the first time since 1855. On 11 January 1916 almost all of the inhabitants of Edenderry were alarmed by the sound of the canal breach. It caused consternation in the town with flooding widespread, crops damaged and animals carried away on farms.

From New Year’s Eve until Tuesday, 12 January heavy rains had caused widespread flooding and thus the canal levels rose. Earlier that day an inspector from the Grand Canal Company visited Edenderry and stated that there was no cause for alarm. However, a loud bang was heard shortly before midnight signalling that something was wrong. The occupants of houses near the Blundell Aqueduct on the Rathangan road were among the first to hear the bang and a few moments later the same houses were flooded. In the hours that followed women and children were lifted to safety, while cattle and animals were rescued by boat. The whole country between the canal and the River Boyne on the Kildare border was flooded. What was once the main artery for trade into the town had now turned villain, threatening people’s livelihoods. Furthermore, the ‘tunnel’ collapsed, causing serious damage to the Blundell Aqueduct and forced the closure of the Rathangan road.

However, the breach had more far-reaching consequences, affecting businesses as far away as Limerick who relied on the route to transport their wares to Dublin. Almost immediately stop gates were erected on the Tullamore side of the town to prevent further flooding. Bog and earth were moved as the breach measured 112 yards long. Greatly affected, Daniel Alesbury and his workers helped in the erection of a dam on the Tullamore side of the town in an effort to stop the breach. Indeed, Alesbury later recalled how he was travelling from Philipstown (Daingean) at the time and was unable to proceed with goods to his furniture factory which then employed close to 500 people. During this effort, three men O’Rourke, Dempsey and Bermingham endeavouring to prevent the flow of water were swept away and narrowly survived with their lives.

To investigate the cause of the breach the Canal Company appointed Gordon Cale Thomas, the world’s leading authority on canals. With the war ongoing it was perhaps to be expected that some would suggest more sinister reasons for the breach. One newspaper account blamed the breach on the ‘Germans’, although it was queried as to what potential benefit the Kaiser would gain by cutting off the Canal at Edenderry!

News of the Edenderry breach appeared on newspapers all over the world including the Honolulu Star, the Irish Standard (Minneapolis) and several in Connecticut. According to the Leinster Leader newspapers visitors from all over the country had gone to Edenderry to see the damage which had been done by the canal breach.

In the days after the breach it was estimated that it would cost more than £50,000 to repair and cover the cost of damages to land which had been inundated with water.

The canal breach was eventually repaired and open to traffic by mid-April, significantly in time for the rebellion, as hundreds fled Dublin, stopping temporarily in Edenderry. Two days before the Easter Rising, on Easter Saturday the Westmeath Independent reported that the canal had been reopened for service