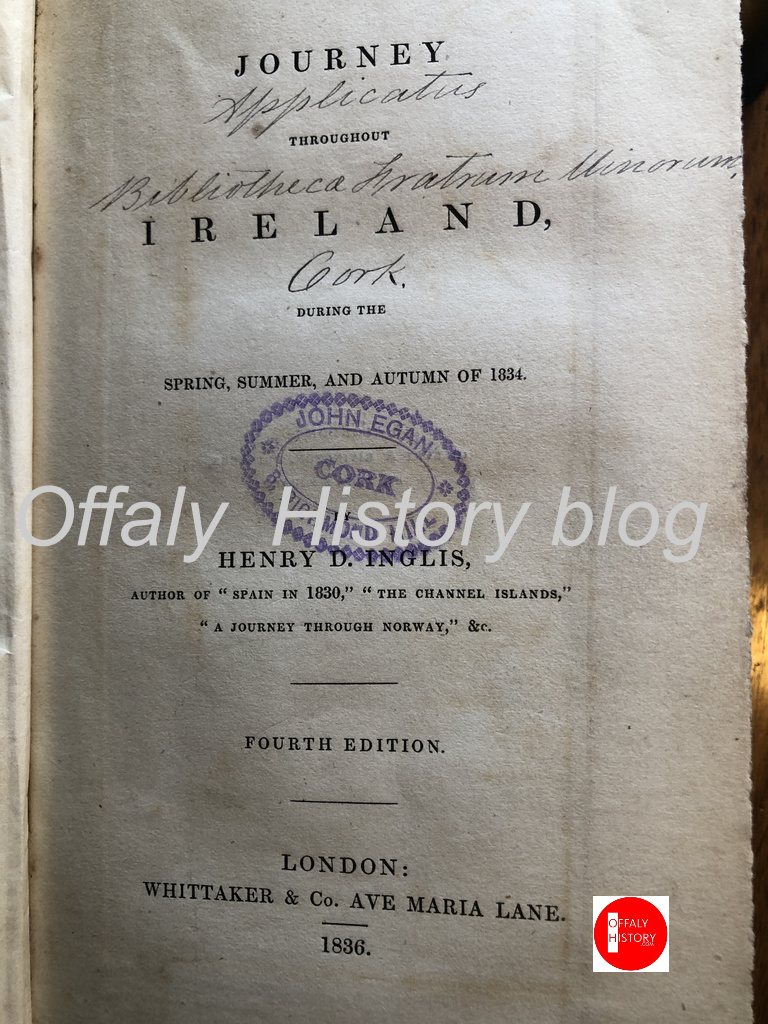

Last week we looked at the history of steamers on the Shannon. Today we take the account of Henry D. Inglis published in 1835. Inglis was a professional travel writer and author of Spain in 1830, A Journey through Norway etc, published his A Journey throughout Ireland during the Spring, Summer and Autumn of 1834 in London in 1835. His account is well thought of and in his concluding remarks he says why jest or narrate the curious and witty eccentricities of Irish character when ‘God knows there is little real cause for jocularity, in treating of the condition of a starving people.’ So there was a degree of sympathy rather than of superiority.

Inglis was born in Edinburgh and was the only son of a Scottish lawyer. His Irish travels volume was published the year of his death, (first edition, 1835, fourth edition 1836). While considered a ‘fairly benevolent interpreter’ he could find no explanation for the Irish situation other than defects of character.

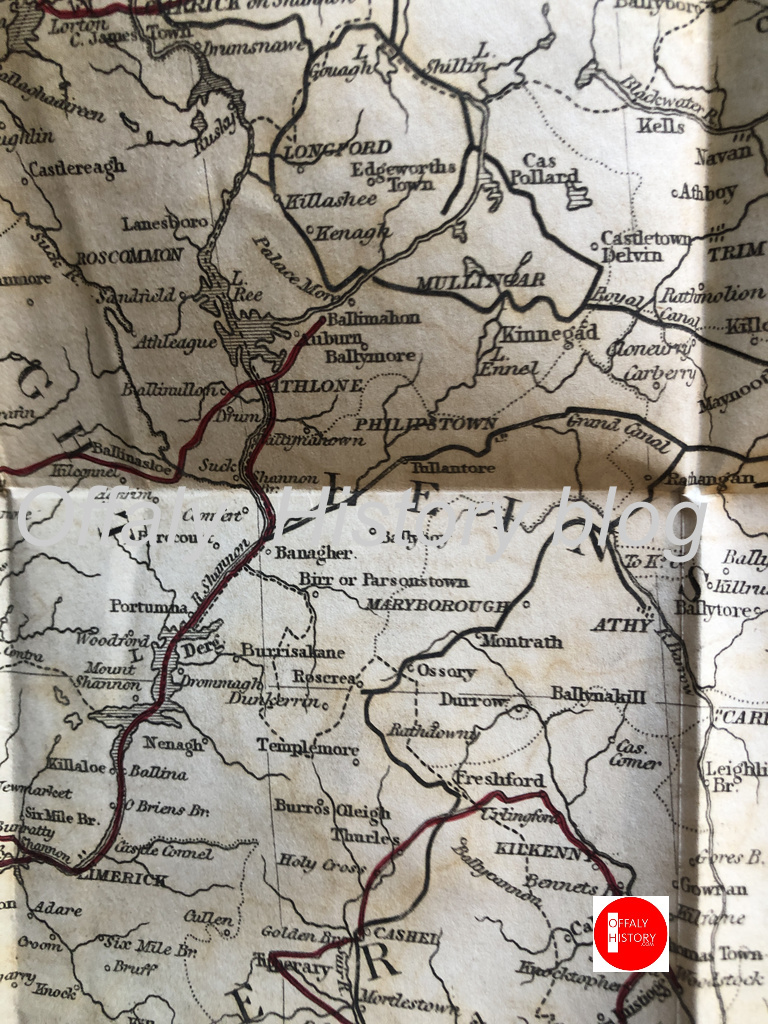

Inglis spent a week there and also visited Killaloe, Portumna and Banagher. He went from Banagher to Athlone by road and thought the latter was a remarkably ugly town – but not withstanding an interesting and excellent business town. He spent a week in Athlone and used it as a base for touring in the county of Longford to see Goldsmith’s Country.

Killaloe [page 182-188]

I hired a small rowing boat to take me up the river to Killaloe, where the steam navigation of the upper Shannon commences. . . . [page 182.] Killaloe, I found an improving town. This improvement arises from several causes; but chiefly is owing to the spirited proceedings of the Inland Steam Navigation Company, … The improvement of the navigation of the Shannon and its tributaries, is deserving of the especial protection and aid of government. Killaloe is the headquarters of the company; and from this point, there is a regular steam communication for goods and passengers up the Shannon, through Loch Derg, to Portumna, Banagher and Athlone; and from the same point, by packet-boat to Limerick, and thence, again, by steam to the sea. It is intended to carry the steam navigation above Athlone, through Loch Ree, to Lanesborough, Carrick, and Leitrim; and when these arrangements are completed, there will be a direct navigation on the Shannon of nearly two hundred and fifty miles, mostly performed by steam; together with a direct water communication to Dublin, by the grand canal

I have ascribed the improving conditions of Killaloe, chiefly to the enterprise of the Steam Navigation Company. This arises in several ways, –partly in the direct employment afforded by the company in the construction of buildings, docks, &c. ; and partly in the general encouragement offered to trade, by the facilities afforded, both for internal communication, and for export trade, which has lately been greatly on the increase. There are also other sources of employment and wealth in Killaloe. The extensive slate quarries in the neighbourhood, afford a yearly export of at least 100,000 tons; and dispense about 300l. weekly in wages: and close to the town, an extensive mill has lately been erected, for the sawing of marble and stone, which are sent there both from Galway and Limerick counties: so that altogether there is little want of employment in Killaloe. The town is very agreeably situated on the rising ground above the river, and within a mile of the noble expansion of water called Loch Derg. An old bridge of nineteen arches, just below the town, connects the counties of Clare and Tipperary; and there is an old cathedral, with a square tower, and Saxon archway of considerable beauty. I attempted to gain the summit of the tower, by the stair inside ; but found it in so ruinous and dangerous a condition that I was forced to give up my attempt.

I stepped on board the steam vessel at eight in the morning, satisfied with everything about Killaloe, excepting the inn, which is far from being what might be expected at the place where the Navigation Company has fixed its headquarters. . . .

We were now within sight of Portumna town and Portumna lodge, –or rather the remains of what was once the fine seat of the Marquis of Clanricarde. Its situation is not particularly happy: the country is flat, and the wood generally of small growth ; and it is believed that the Marquis will ever again rebuild his mansion. The great reach of Loch Derg, through what I have just conducted the reader, contains upwards of forty islands, varying in size from a mere point, to the circumference of perhaps two English miles. The loch, not reckoning in its width the great reach, which has Clare on one side, and Galway on the other, is from one to three miles broad. The depth is very variable. There is however, everywhere a sufficiency of water for all the purposes of navigation. The length of this expansion of the Shannon from Portumna to Killaloe is twenty-three miles. [page 188]

From Portumna to Banagher and Athlone

Inglis travelled in one of the new steam vessel to be found on the Shannon from the late 1820s. These vessels made it possible to negotiate the Grand Canal and the River Shannon from Dublin to Limerick with a high degree of comfort.

Portumna enjoyed the benefits of the new linkage and had a good export and retail trade but a not very enterprising landlord in the shape of the Marquis of Clanricarde. Banagher he found to be one long street with the old bridge still intact. It was replaced in the mid-1840s by the present bridge in the course of the Shannon navigation works.

[page 188, vo. 2]

“The town of Portumna lies about a quarter of a mile from the river, and I had only time for a flying visit; for I wished to take advantage of the fine evening, and go forward to Banagher, in the small river steamer, to which the passengers from Killaloe are transferred. Portumna is a place of considerable export trade to Dublin, and enjoys a good retail trade besides; but the improvement of the town is much checked by the disinclination of the Marquis of Clanricarde to grant good leases.

The distance up the river, from Portumna to Banagher, is fourteen miles and a half; and by the bye, I must not omit to note the expense of travelling by steam on the Shannon. The distance from Killaloe to Banagher, is thirty-eight miles; and for this, the charge is 6s. 4d., or 2d. per mile. The charge is certainly not high; and I understood that the only ground of complaint – the slow rate of travelling – was on the eve of being removed, by the employment of a new steam vessel of greater power. The company has already done wonders; and it would be absurd, as yet, to expect perfection.

[The River Shannon – what a great water it is]

To the lover of the picturesque, the banks of the Shannon, between Portumna and Banagher, present little that is attractive. But to other minds, there may be an interest of perhaps a higher kind. We are navigating in a steam [page 189] vessel, a river, here a hundred and thirty miles from the sea; and we know it to be navigable nearly a hundred miles higher. Its volume appears to be as great as when we saw it at Limerick: it is several hundred yards broad; and twenty and thirty feet deep. What a body of water is this! What are the Thames, the Medway, the Mersey, the Severn, the Trent, the Humber, the Tweed, or the Clyde, a hundred and thirty miles from the sea? I am not sure if they exist at all; or if any of them do, they are but brawling streams for the minnow to sport in. There is, in fact, an approach to the sublime, in the spectacle of such a river as this; and the feeling receives aid from the character of its banks. These are wide, and apparently interminable plains, uninclosed, – almost level with the river, – bearing luxuriant crops of herbage, and feeding innumerable herds. We see scarcely any habitations: no villages or hamlets; and no road or traffic on the banks. The meadows of which I speak extend on both sides of the river, the greater part of its course from Banagher to Portumna. These meadows are all overflowed during the winter, and are let for grazing at a very high rent. For many miles, there is nothing to relieve the monotony of these vast flats, excepting an old castle, called Torr Castle, – not otherwise remarkable than as being the only object which breaks the level. The views on this part of the Shannon, brought forcibly to my recollection, the banks of the Guadalquiver, between Seville and Cadiz [remember his 1830 book on Spain].

[Linking the Little Brosna to the Shannon ?]

Six or seven miles about Portumna, the river branches out, leaving several flat green islands; on one of which a Martello tower, once a defence against the people of Connaught, is still foolishly kept up. The ruins of Meeleck [sic] monastery, too, on the Galway side, attract the attention. They appeared to be both fine and extensive. It is here, that the lower Brusna river falls into the Shannon. It is the boundary line betwixt the provinces of Leinster and Munster; and is one of those aids, which may be brought to bear advantageously on the Shannon navigation. From the [190] point of junction, it is only eight miles to the town of Birr, and at a very moderate expense, the Brusna may be rendered navigable.

From this point to Banagher, the river flows in various branches, leaving not fewer than twenty islands, great and small. The country on both sides, too, begins to improve; and to assume greater variety. Wood, though but of scanty growth, begins to appear, and the ground rises into some considerable elevations. I reached Banagher a little before dusk, and found excellent accommodation in the only hotel. This town, like all the others on the line of the inland navigation, is progressively advancing. There is a good corn market, a considerable export, and a thriving retail trade. The town itself has little in its appearance to recommend it. It consists chiefly of one very long street; and has some batteries on the Connaught side; and a bridge of nineteen arches.

To have had the advantage of a steam vessel from Banagher up the river to Athlone, I should have been obliged to have remained at Banagher several days; for at present, this convenience occurs only twice a week. I sufficiently ascertained, however, that by travelling to Athlone by land, I should lose little in the attractions of scenery. The river, from Athlone to Banagher, flows through a wide tract of bog land – even more uninteresting than the meadows which extend between Portumna and Banagher. The only relief from this monotony, is the Seven Churches [Clonmacnoise], – ruins, which stand close by the river, about tend miles above Banagher.

I hired a car to Athlone, and left Banagher the day after I arrived in it. Here I found a change in the expense of travelling. Posting by car, had hitherto been everywhere 8d. per mile; but I now found, that the price varied with the number of persons using the car. If one person only travels the price is 6d. per mile; if two travel, it is 8d.; if three travel, it is 10d.

For some miles after leaving Banagher, the road keeps near to the river; and then passes through the station, [p. 190] called Shannon Harbour, where the Grand Canal to Dublin connects itself with the Shannon. From this point, there is a regular communication daily; both to Dublin, and, by steam, on the Shannon to Limerick. A little beyond Shannon harbour, we crossed the upper Brusna river, at a point where the wood scenery is extremely beautiful, and where also, the fine domain of Colonel L’Estrange skirts the road [Presumably he is referring to Moystown House (now demolished) and once the residence of the L’Estrange family.]

Soon after, we entered that wide tract of bog land, which I have described the Shannon as traversing. It extended on both sides of the road, as far as the eye could reach; and presented under the influence too, of a dull atmosphere, as dreary a prospect as can well be conceived. The Bog of Allen, which traverses a great part of King’s County, lay on our right: and the bogs of Galway stretched away to the left. Occasionally, as the road ascended some trifling elevation, the Shannon was discovered, winding its brimful course, through the low, wide, brown, bog lands, which extended far on either side of it. To the utilitarian, even this prospect is not deficient in interest. Turf – that article of prime necessity in Ireland – is not equally abundant in all parts; and here, in the extensive bogs through which a great river flows, there is security for an abundant and cheap supply of fuel to parts the most remote.

The road between Banagher and Athlone, I found one of the worst I had seen in Ireland. Few gentlemen’s seats are in its neighbourhood; and therefore, it is nobody’s interest to make a job [i.e road making by the grand jury] Some considerable distance before reaching Athlone the country improves, and the immediate neighbourhood of the town is finely diversified and well cultivated.”

_________

Athlone is a remarkably ugly town. So deficient is it in good streets, that after I had walked over the whole town, I still imagined I had seen only the suburbs. But it is, notwithstanding, both an interesting town, and an excellent business town. It stands in the midst of a well cultivated and thickly peopled country; and both in its export and general trade, is rapidly improving. At least eighty tons, chiefly corn, are sent down the Shannon, on a weekly average, by The Navigation Company. The bridge is extremely ancient, and is in a disgracefully ruinous condition. In many places the parapet wall has given way; and the carriage road is so narrow that, on a market-day, it frequently happens that one can pass in no other way than by jumping from cart to car and from car to cart. The bridge is altogether a disgrace to the town and the kingdom. Notwithstanding that between Athlone and Portumna, the Shannon receives the two Brosna rivers, the Suck, and many smaller tributaries, it appears at Athlone, to carry an undiminished volume of water. Above Athlone bridge—upwards of a hundred and fifty yards wide and ranges from twenty to thirty-five feet in depth.

Athlone is a great military station. Extensive barracks, both for foot regiments and for artillery, lie in its immediate neighbourhood; and on the Connaught side, a line of fortifications has been erected. In the very centre of the town, too there is an ancient castle, with a strong central tower, and massive bastions. All these places are fully garrisoned. Athlone, I made my head-quarters for a week; and, from it, made excursions through different parts of the county of Longford. Independently of my chief objects of inquiry, another object of interest presented itself, in the reputed birth place of Goldsmith, and in the scene of “The Deserted Village,” to both of which I shall by and by return.

Ballymahon was one of my central points. This is a town about ten miles from Athlone, and capable of much improvement. A very fertile country surrounds it : it is sufficiently near to water communication ; and some idea may be formed of the extent of its market, when I mention that from 300L to 400L worth of eggs have been sold on one market-day. The town and its capabilities are, however, utterly neglected by the proprietor, who grants no leases and acts—as a great majority of landlords do—as it he had no interest in the permanent improvement of his property.

Land, throughout the county of Longford is, with few exceptions, let high, but there are exceptions. Lady Ross forms one of these. The land on her ladyship’s estate is well worth the value put upon it, and with a little more skill and industry, would afford even higher rents than are exacted. But there is a lamentable want of good husbandry; clean farming appears to be unknown : every-where fields are seen covered with crops of weeds, to be ploughed, in as manure; and nowhere is there visible anywhere of the neatness and care which are indicative of industrious habits.