In early 1916 the Foresters accommodated a support dance for the war effort and a ceilidh organised by the new branch in Tullamore of Cumann na mBan. A report of the first Ceilidh Mhór of Tullamore branch of Cumann na mBan held in the Foresters in early January had over 100 couples in attendance. The Tri-colour prominent in the hall was that ‘of the ’48 men, green, white and yellow’. The decoration of the hall was carried out by a ladies committee of Cumann na mBan assisted by Messrs Bracken, McNally and others (all prominent in the First shot episode in Tullamore in March 1916).The president of the branch was in attendance, Mrs P.F. Adams, as was P.F Adams. The Ladies Committee included McBrian, Mooney, Neary, Conway, Galvin while Messrs Alo Brennan, Seamus Connor and H. McNally and Miss Long assisted. These men and women were all prominent in the national movement and the breakaway minority group from Redmond’s Volunteers.[1] In a strange decision Adams gave up his seat on the county council in February 1917 in favour of the Limerick-born T.M. Russell, the new full-time local organiser for Sinn Féin. The Foresters were not happy that Tullamore now had no representative on the council except ‘this new man’.[2]

St Patrick’s Day in 1917 was the first occasion locally to mark the deaths of the leaders in the 1916 Rising. The local Independent was able to record that:

St Patrick’s Day passed over very quietly in Tullamore. ‘There was a good attendance at all the masses. All young and old wore the Shamrock, and the tri-colour surmounted by the chosen leaf was very much in evidence, being worn by the younger men and women. St. Bridgid’s Pipers Band made its first public appearance unhindered by the police several of whom accompanied. Established some months ago by two members of the St Colmcille’s Band, Durgan and O’Looney. On Patrick’s night a successful concert was held in aid of the band in the Foresters.

But it did not stop there. A few weeks later the Independent carried a report of a prosecution under the DORA (Defence of the Realm) provisions against Mr James O’Connor, a coach builder, until recently in the employment of P. & H. Egan and E. J. O’Carroll, boot merchant of William Street arising out of the concert held in the Foresters on St. Patrick’s Night. Henry Brenan as crown solicitor was prosecuting. The charge related to alleged seditious statements and seditious poetry and aiding and abetting one Lena McGinley ‘in an attempt by her to cause disaffection’. McGinley recited the poem Vengeance. She was 11 or 12 years old and dressed in a ‘Sinn Fein costume’ – green, white and gold. So stated Sergeant Cronin who with two other constables who were on duty at the concert. James Rogers defended. Both men were found guilty and were bound over, without fine, for twelve months to keep the peace, and give bail or in default two months. Both declined to give bail. O’Connor was said to be an organiser in that he collected the money at the door and Carroll was a stage manager. Both were lodged in Mountjoy.[3]

In the meantime the Foresters continued its cinema programme with the all the leading films of the period and including a showing of a film of the funeral of Thomas Ashe in October 1917.[4] The continuing pluralist approach of the Foresters was shown in 1918 with Countess Markievicz and Maud Gonne on a visit to Tullamore for the performance of a play by T. M. Russell – the Sinn Féin organiser. This was followed soon after by a lecture by barrister Henry Hanna on the Pals of Suvla Bay (the same title as his book – copy in OH Library). In April it was the anti-conscription meeting held outside the Foresters’ Hall. In October the film series Patria was shown to packed houses ‘with musical selections by the Murphy orchestra’.[5]

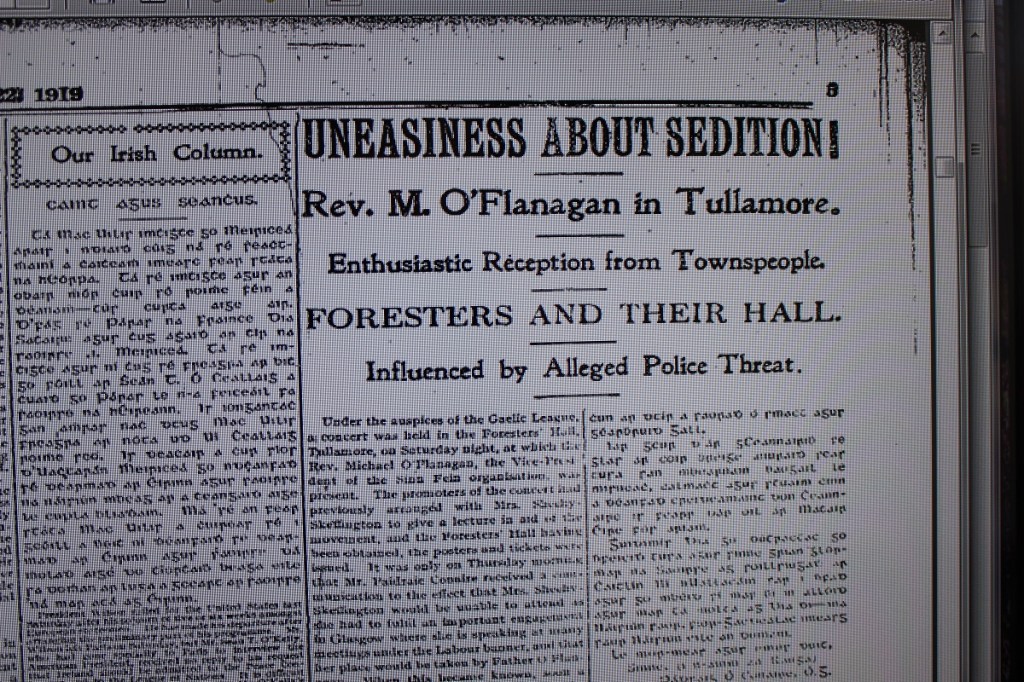

The war was barely over when the Spanish ‘flu arrived causing death, the closing of schools and the cinema.[6] By February 1919 it was largely back to normal and the Foresters had one of its largest attendances in years with 240 present and the health of Chief Ranger Philip Reilly proposed. P.F. Adams was recalling the night twenty ago when the Foresters was started.[7] A few weeks later it was the turn of Fr Michael O’Flanagan, vice-president of Sinn Féin, to speak in the hall, standing in for Mrs Sheehy Skeffington. The talk was under the auspices of the Gaelic League. O’Flanagan got a rousing reception.[8] It was a difficult one for the Foresters as they had been warned by the police that the Foresters Hall committee would be held responsible for any seditious utterances and initially refused to make the hall available unless undertakings were given. Fr O’Flanagan refused and it was the threat of forcible entry that allowed the meeting to proceed. This came about as large numbers were waiting to gain admission to the locked hall including prominent clergy such as the republican Fr Burbage of Geashill. Fr Burbage when asked to sing in the concert said he would only sing a song lest should catastrophe befall them – alluding to the three policemen present including Sergeant Cronin (he was shot and killed nearby by the local IRA on 31 October 1920).[9]

The War of Independence was more earnestly fought by 1920 with the burning of barracks and the attempted burning of Clara barracks defeated. The killing of Sergeant Cronin in Henry Street, Tullamore, only a stone’s throw from the Foresters’ Hall, on 31 October 1920 was said to be in retaliation for the death on 25 October of Sinn Féin lord mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney. Young Kevin Barry was executed on the same morning as Sgt Cronin died. And so the cycle of violence, which apparently meant so little to war-hardened Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, would have its local as well as its national impact far into the future. In Tullamore the Cronin killing was long remembered for the reason that it was largely an isolated incident in the War of Independence in Tullamore and the fact that members of Sergeant Cronin’s family were prominent in Tullamore in the 1950s and 1960s, in particular, his son Archbishop Patrick Cronin and his daughter Peggy who worked for many years in Hoey & Denning, Solicitors.[10] It was also remembered as the night that the Black and Tans burned the Foresters Hall.

After the news of the shooting many people in Tullamore fled their homes. The Foresters’ Hall was burned on the night following his death as were the shops of well-known Sinn Féin sympathisers – Mrs Teresa Wyer (chair of the board of guardians), O’Brennans of Church Street and the hairdressing establishment of James Clarke in William/Columcille Street. Also damaged were the offices of the Offaly Independent, the Sinn Féin rooms overhead and the Transport Workers Hall. Houses visited by the Black and Tans included that of Whelan’s in O’Connell Street, Mrs Mooney, Crowe Street, Barry’s in O’Moore Street, Taylor’s in the same street, Kelly’s in High Street, Daly’s and Digan’s in Cormac Street. James O’Connor, the town councillor and president of the local branch of the Transport Union, was resident in Mrs Heavy’s in Harbour Street and having been seized by the police was lucky to escape. Curfew was imposed in Tullamore during darkness and searchlights were in operation. Black and Tans behaved in a lawless fashion in many of the midland towns, even Birr much to the surprise of residents there.

The Foresters then moved to Market Square to a premises, later used as a snooker hall in the 1980s. In 1922 the branch successfully applied for compensation for the loss of their hall to the British government. The claim was for £15,000 and it was settled quickly at £13,00 by a Mr MacAuley, the assessor on behalf of the Shaw Commission and the Foresters’ solicitor Joe Kearney of Conway & Kearney.[11]

Mr. McAuley, the Official Assessor of Lord Shaw’s Commission, visited Tullamore on Tuesday in connection with the claim of the Tullamore Branch of the Irish National Foresters for compensation for the burning of their Hall on the morning of November the 1st 1922. The application was heard before his Honor, County Court Judge Fleming, at the Birr Quarter Session in March, 1921, when it was opposed by the Tullamore Urban Council only, there being no appearance on behalf of the Co. Council. The County Court Judge granted a decree for £15,000 with costs, but, owing to the fact of this claim not having been opposed by the Co. Council, it became subject to revision by the Shaw Commission, The Assessor having met the Commission, of Management of the Foresters’ Society with their solicitor, Mr, Kearney, (of Messrs Conway and Kearney), went very minutely into the details of the claim, and made an award for £13,000, with costs.[12]

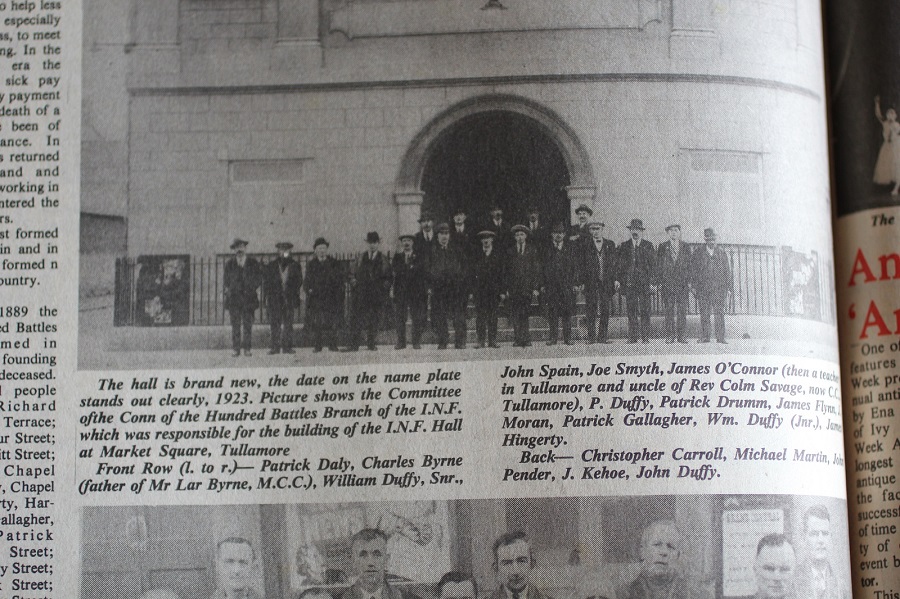

During that year the compensation money was invested in the formation of the “Tullamore Co-Operative Society” and the commencement of the co-operative bakery. The bakery was formed on the initiative of James O’Connor. He joined the I.N.F. in 1912 and the bakery was originally housed in premises owned by the O’Connor family. The formation followed a strike in local bakeries. The Co-Op then purchased a site where James Morris and Sons furniture store now stands and the bakery was transferred there. The business, however, was short lived. It closed in 1923. As the major shareholder in the property the Irish National Foresters acquired the property. The committee immediately set about building a dance hall, club rooms and a cinema.[13]

The Foresters acquired additional land from Lady Emily Howard Bury of Charleville. The site was part of the former Shambles which had been opened as a food and meat market off the Market Square in 1820. The new complex cost the Foresters close on £7,000 in all according to one source.[14] Alesburys of Edenderry were responsible for the new cinema seating while the design was that of T.F. McNamara who had taken over as architect of the new Catholic church (completed in 1906) from William Hague. The engineer was William Holohan, the town surveyor in Tullamore, and the builders were Duffy Brothers, Tullamore.[15] The manager of the new theatre was Andy Gallagher and the projectionist Tony Heffernan.

The opening night on 15 March 1924 featured a Senor Augustin Martini with songs from Italian opera, local contributions and a small orchestra. The Chief Ranger that year was Peter Duffy and he it was who introduced the General Secretary of the I.N.F., Joseph Hutchinson, who said the hall and cinema theatre was possibly the finest in the whole organisation.[16] It was the 25th anniversary of the Society and the high point in its progress.

The Foresters continued to run dances into the 1930s. That decade was a colder climate for women than back in 1912. It was post the Juries Act of 1927 and the dancing restrictions of the same year. When Joe Kearney was seeking the renewal of the Foresters’ dance licence in 1935 Judge Austin O’Donoghue wanted to know were ladies able to access the bar via a cloakroom. Kearney said no that ladies did not access the bar, but for the garda superintendent helping out it might have proved even more difficult to get the renewal. The judge granted the licence to allow six dances in the year to 2 a.m. and a weekly dance to 11 p.m., no one under 18 or showing signs of drink to be admitted.[17]

It is said that the network of branches of the Foresters began to crumble in the late 1920s. Tullamore branch survived although membership declined. It is now the last surviving branch in the Republic of Ireland. Within six years of the opening of the cinema the Foresters had leased the property to Messrs Mahon and Cloonan who called the place the Grand Central Cinema and went on to open a second cinema in High St (the Ritz) in 1946.[18] The opening season of the Grand Central included the first ‘Talkie’ seen and heard in Tullamore.[19] Both cinemas were sold in the early 1980s. In the late 1980s the Grand Central was converted to use as a bar and restaurant. It would have made a good theatre but like the sale of the market house in 1960 and again in 2016 Tullamore people did not rise to the occasion.

The Foresters continued to march on St Patrick’s Day, but it is nothing like it was in that glorious first twenty-five years. In that period the Foresters fully embraced the innovations in social and business life very much associated with the first two decades of the twentieth century. That said it was a second home to Tullamore stalwarts right up to the 1980s when the first and second generation of members had passed on. These were the people who had secure jobs in Williams, Egan, the bacon factory perhaps Salts. All that changed too in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s with the closure of long-established businesses.

[1] Ibid., 5 Jan. 1916

[2] Tullamore and King’s County Independent, 3 Mar. 1917.

[3] Tullamore and King’s County Independent, 24 Mar. 1917. 28 Apr. 1917.

[4] Ibid., 29 Sept. 1917, 6 Oct. 1917.

[5] Ibid., 16 Feb. 1918, 20 Apr. 1918, 12 Oct. 1918.

[6] Ibid., 1 Feb. 1919.

[7] Ibid., 8 Feb. 1919.

[8] Ibid., 22 Feb. 1919.

[9] Ibid.

[10] See earlier blogs in this series at http://www.offalyhistory.com including that of the killing of Sergeant Cronin published on 31 Oct. 1920.

[11] Offaly Independent, 11 Nov. 1922.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Tullamore Tribune, 18 Aug. 1984

[14] Offaly Chronicle, 26 Apr. 1923.

[15] Offaly Independent, 4 Feb. 1922, 18 Nov. 1922, 21 Apr. 1923.

[16] Offaly Independent, 22 Mar. 1924.

[17] Offaly Chronicle, 31 Oct. 1935.

[18] Offaly Independent, 12 Apr. 1930.

[19] Ibid., 26 Apr. 1930.