Let Erin remember the days of old

Alongside John O’Donovan and Eugene O’Curry the name of George Petrie (1790–1866) will forever be remembered as one of Ireland’s greatest scholars of the first half of the nineteenth century. It was a time when tremendous work was done for Irish archaeology and history. Petrie was a major figure in the historical research section of the Ordnance Survey. Jeanne Sheehy in her The Rediscovery of Ireland’s Past 1830–1930 states that he was the founder of systematic and scientific archaeology in Ireland.

Petrie was involved in the work of the Ordnance Survey from 1833 for ten years. He was very much a polymath and in his late years published a volume of Irish music arising from his efforts to collect and preserve old Irish music.

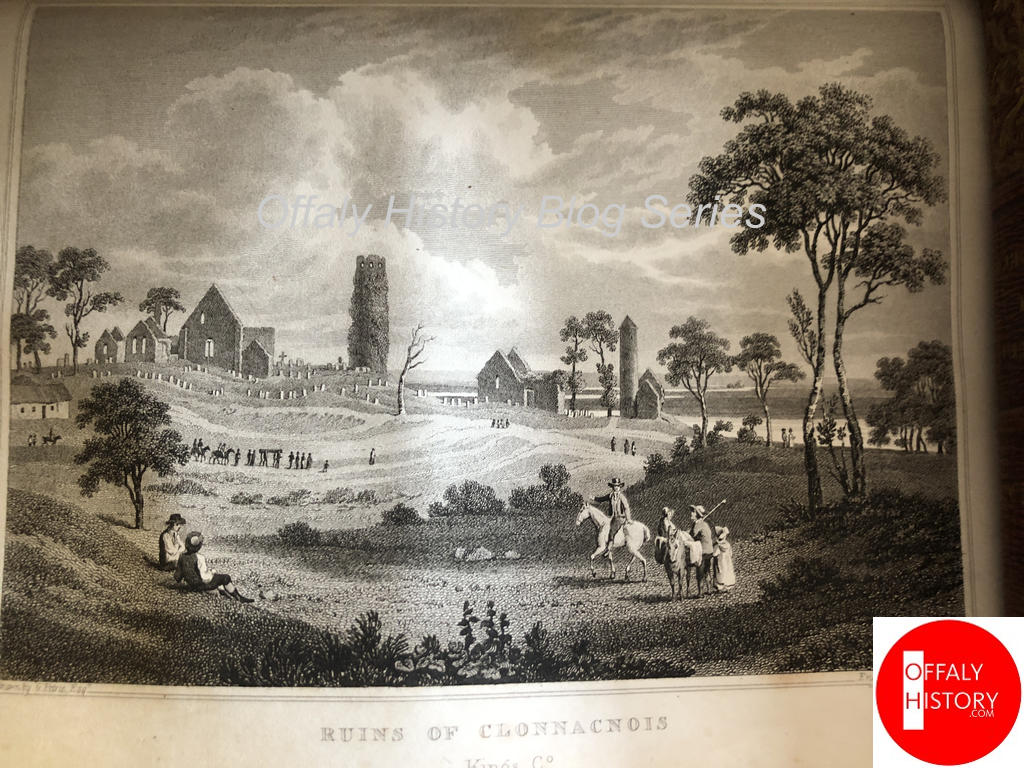

George Petrie was born in Dublin in 1790 and has a strong King’s/ County Offaly connection through his work at Clonmacnoise, Birr, Banagher, Clonony, Durrow, Lemanaghan and Rahan. He may have been the most significant topographical artist so far as Offaly is concerned. He was certainly the greatest exponent of the heritage of Clonmacnoise first visiting the site in 1818–22. Dates differ as to the visits to Clonmacnoise as was noted in the most attractive publication by Peter Murray and published by the Crawford Gallery in 2004.[1] The other great work on Petrie is that of William Stokes, The life and labours in art and archaeology of George Petrie (Longmans, London, 1868). Also helpful is Crookshank and Knight of Glin, Irish painters, 1600–1940 (Yale, 2002). Petrie died in 1866 and is buried in Mount Jerome cemetery.

Of his first impressions on visiting Clonmacnoise, in 1820, George Petrie wrote:-

‘It was not without a considerable feeling of romance that we approached this, the most interesting spot that our island affords; nor without some emotion of awe that we entered its lonely and sacred precincts. Once the chief seat of piety and learning of the Insula Sanctorum, now a place hardly known to the inhabitants of Ireland, yet for ages held the most sacred and venerated; the Iona of Ireland, which her princes embellished, and containing the tombs of her noblest in blood. Journeying thither, we indulged our fancy in such pleasing anticipations as that we should find, among the ruins of those ancient temples, sufficient evidence that Ireland was not ignorant of architectural art, as practised in Europe during the early ages of Christianity; and that among the tombs we should discover inscriptions which would show her ancient history was not, as is generally believed, a fable. Those pleasing hopes were more than realized.’[2]

Sketching Birr Castle

The following letter to his newly married wife has an interest in showing that while employed in working for the public taste as a professional artist, he was not unmindful of those higher objects to which he had at so early a period directed his attention. The letter is reproduced from William Stokes, The Life and Labours in Art and Archaeology of George Petrie, (London 1868), p. 27.

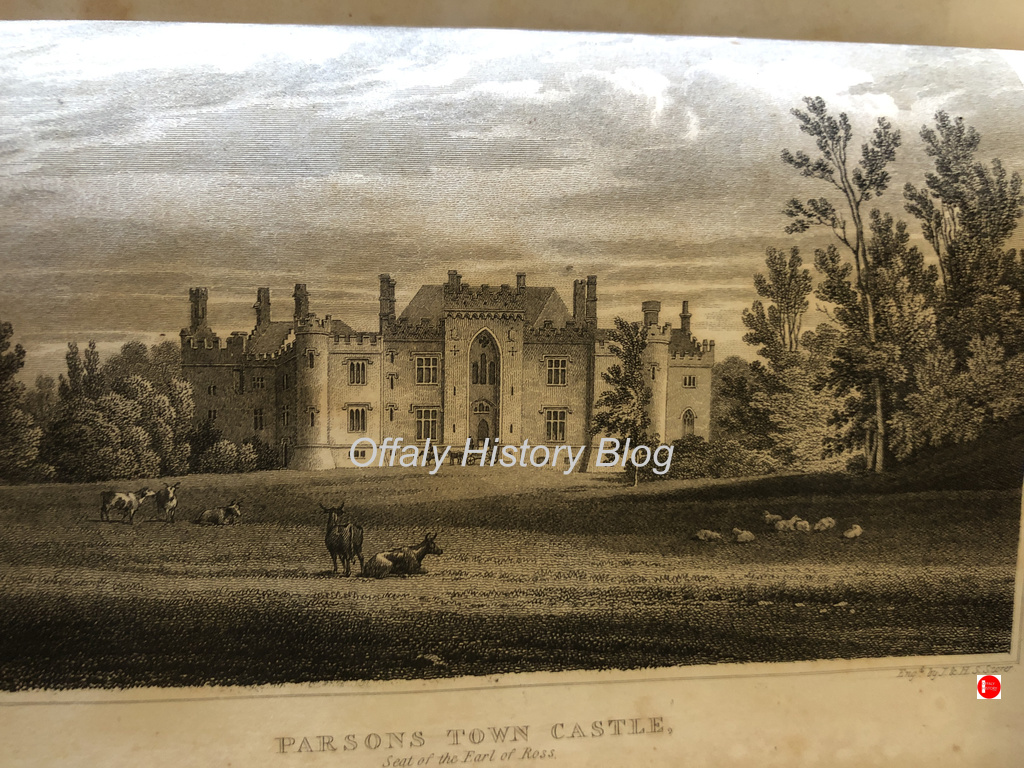

Birr, August 1st 1820

I have been for two days at Clonmacnoise, a wild spot on the banks of the Shannon, where there are the remains of ten or eleven churches and two round towers. I have got some delightful subjects, and have been so singularly fortunate as to meet with several Irish monumental inscriptions of the sixth and seventh centuries, which will go farther towards establishing the truth of our ancient records, than all the writings of the learned for the last two hundred years The event has, in truth, put my mind into a greater state of fermentation than I can recollect to have experienced for several years. Today I have been till now (four o’clock), sketching a nobleman’s seat here (Lord Rosse’s) which, though very fine, cost me a great deal too much time; but, in fact, it has been the same with all the subjects of that character which I have hitherto done; less than four or five hours will not suffice for one sketch. The weather continues broken and windy. I should not have been able to sketch today but for the leeward side of a haycock, which I had the good fortune to meet with. Notwithstanding the very bad weather we have had, I have made a considerable number of sketches for the time.’

Geo. Petrie.

In Stokes’ Memoir was published an account of Clonmacnoise written by Petrie, possibly in 1818–22, or shortly afterwards and as follows:

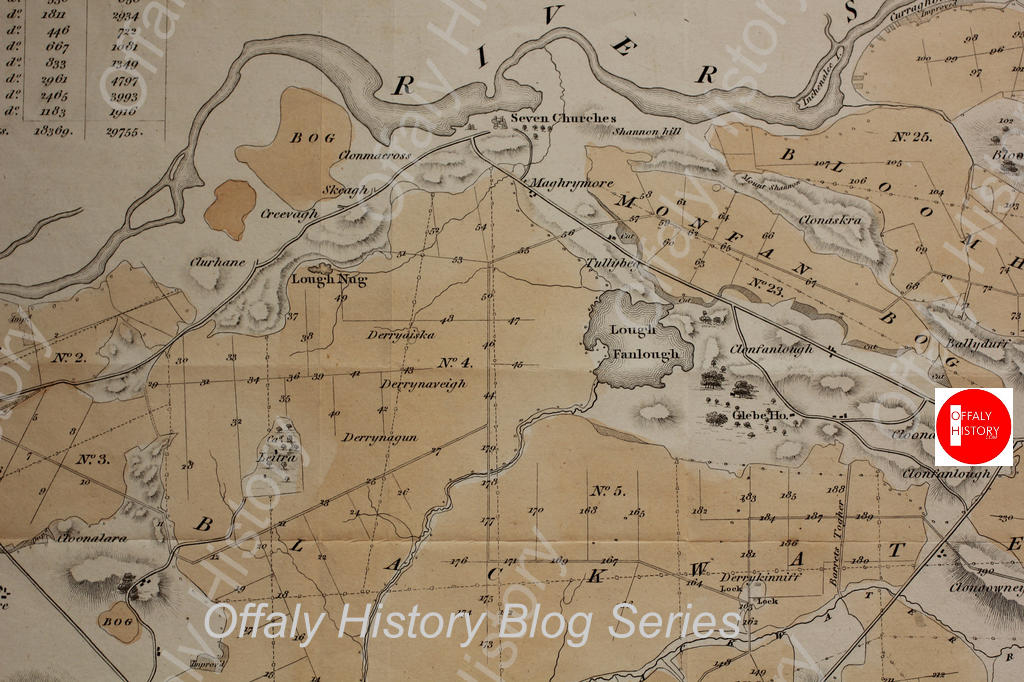

The road from Shannon Harbour to Cluain M’Noise presents no interesting feature. Extensive views of flat moory ground partake indeed of the character of desolation that surrounds and harmonizes with the solitary ruins we were journeying to, but not sufficiently so to affect the mind, and we look in vain for the Irish Ganges, the mighty Shannon, which is shut out from view by a range of calcareous hills along the eastern shore, to relieve the mind from the oppression of the surrounding dreariness.

At about a mile from Clonmacnoise we ascended these hills and saw the ivied round towers on an eminence below us, but the Shannon was still concealed, and neither the towers nor the scenery assumed a striking character till, on descending through these hills, we found ourselves suddenly among the ruins on the bank of the great river. Here, indeed, we looked at each other with expressions of excited astonishment, and involuntarily exclaimed, “This is worth having travelled for.”

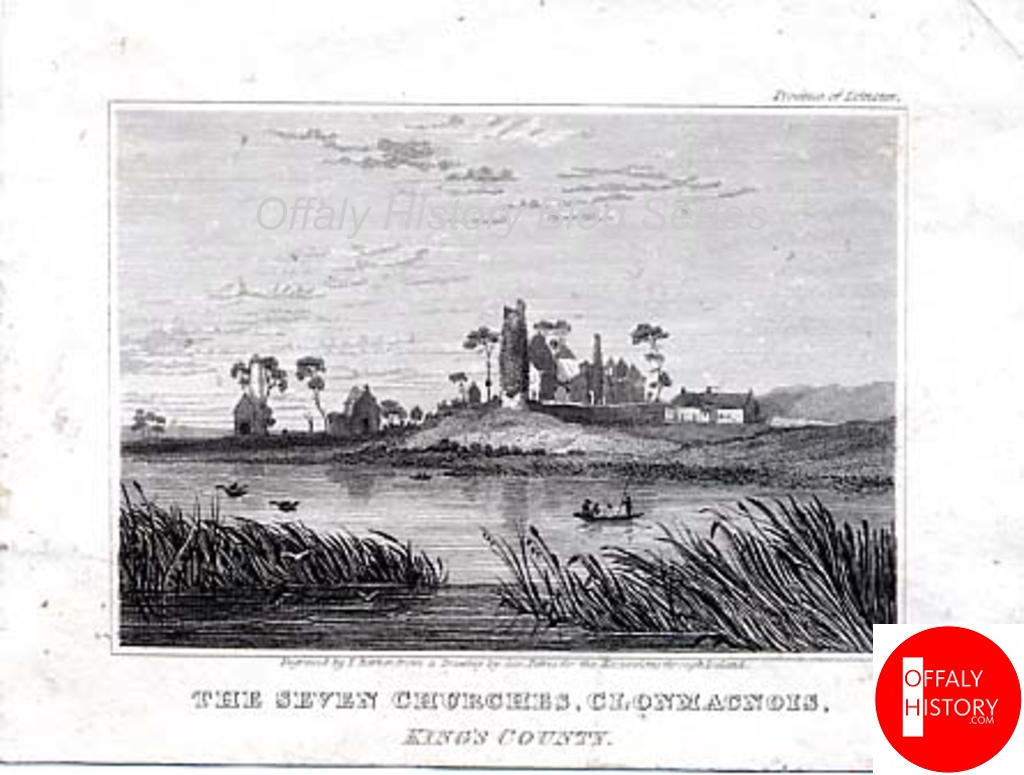

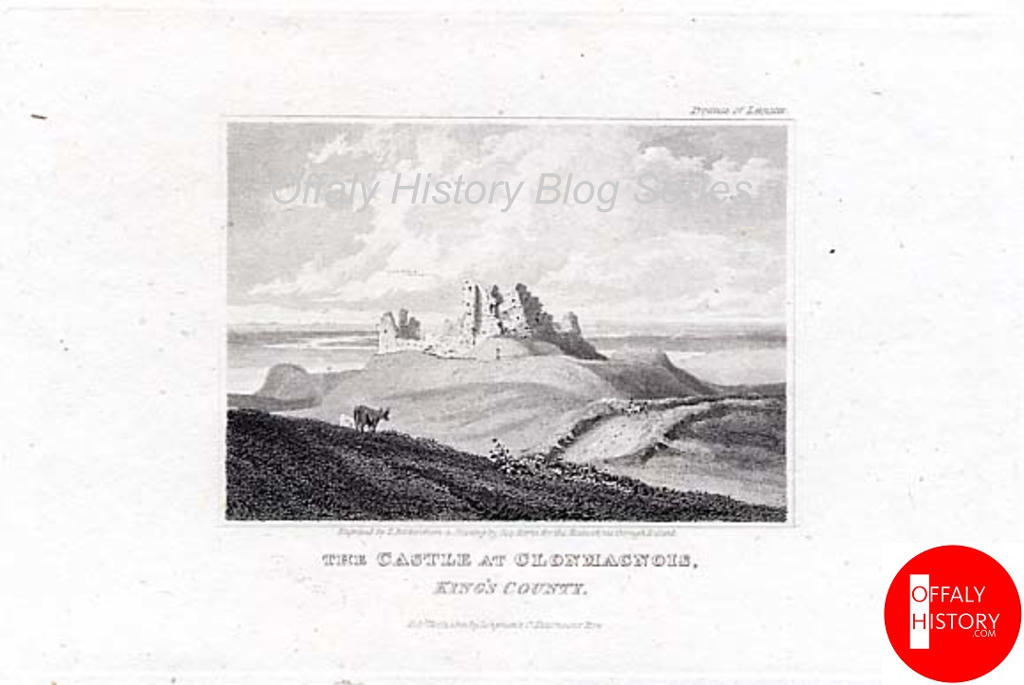

Let the reader picture to himself a gentle eminence on the margin of a noble river, on which, amongst majestic stone crosses and a multitude of ancient grave-stones, are placed two lofty round towers and the ruins of seven or eight churches, presenting almost every variety of ancient Christian architecture. A few lofty ash trees, that seem of equal antiquity and sanctity, wave there nearly leafless branches among the silent ruins above the dead. To the right an elevated causeway carries the eye along the river to the ruins of an ancient nunnery, and on the left still remain the ruins of an old castle, once the palace of the bishops, not standing, but rather tumbled about in huge masses on the summit of a lofty mound or rath, surrounded by a ditch or fosse, which once received the waters from the mighty stream, now no longer necessary. The background is everywhere in perfect harmony with the nearer objects of this picture; the chain of bare hills on either side, now sere and wild, but once rich with woodland beauty, [29]shut out the inhabited country we so lately left, and the eye and mind are free to wander with the majestic river in all its graceful windings in an uninhabited and uninhabitable desert, till it is lost in the obscurity of distance! Loneliness and silence, save the sounds of the elements, have here an almost undisturbed reign. Sometimes, indeed, the attention is drawn by the scream of the wild-fowl, which inhabit this solitary region, or the shot of the lonely sportsman. At other times we could hear the measured time of the oar, or rather paddle, of a solitary boat, long before the little speck in the water became visible; and the melancholy song of the shepherd or the milk-girl, might sometimes be heard in the boggy flat, although the singer was too remote to be visible. To such sounds I have been glad to turn for company during the course of the day.

Readers who have no experience of the feelings excited in the mind by scenes like this, can have little idea of the deep effect they are capable of producing, and will, perhaps smile when I tell them that I have felt a degree of regret when the song of the milk-girl ceased, and the paddle of the boatman would no longer be heard, and when the little dusk figure of the fisherman was no longer found on the margin of the river, like the depression caused by parting with a friend whom we do not expect to meet for a long time again.

This landscape, so striking and harmonious, is rendered still more affecting by the appropriate figures of groups of pilgrims that give at once increased interest and picturesqueness to the scene.

This is but an outline of Clonmacnoise, such as may be intelligible to general readers. The deep interest which this astonishing place afforded in detail, can only be appreciated by the enthusiastic painter or accomplished antiquary. The former will understand the kind of delight with which I was inspired by those groups of pilgrims, clothed in draperies of the most picturesque form, and the most splendid and varied colours. The aged sinner supported by his pilgrim’s staff, barefooted and bareheaded, his large grey coat, the substitute for the forbidden cloak or mantle, sweeping the road, his white hair floating on the disregarded wind! The younger man, similarly attired, whose face betrays the deepest guilt, hurrying along with energetic strides. The females of all ages, to whom uninquiring faith and enthusiastic devotion seem natural and characteristic; but, above, all, the young and beautiful [30] girl, with pale face, blue eyes, long black eye-lashes, and dark hair, whose look betrays no conscious guilt, in the midst of her sighing prayers, but rather a feeling of love and devotion; who, notwithstanding her religious duties, is not so entirely unconscious of the power of her beauty, but that she can spare an occasional glance towards the strangers who are endeavouring to fix her figure on their paper or on their memories – a figure, as a friend well observed, that no one but Raphael could draw.

Such are the poor remains of the once celebrated Cluainmacnoise, for a considerable time the chief retreat, not alone of piety, but also of such learning as the age possessed. A place which the petty kings of three of the provinces of Ireland contributed to adorn; a spot so sacred, that all who were high in the land desired it as their last resting-place.

Petrie, an able scholar, has given us a second account of his visit and of that of pilgrims to the site. In 1828 Petrie completed his well-known painting of The Last Circuit of the Pilgrims at Clonmacnoise. Some ten years later this work was redone on a large scale for the Royal Irish Art Union for 100 guineas. The picture, in Fota House, Cork, for a time, is a romantic treatment of pilgrims visiting the site and Petrie explains his approval of the painting in a letter reproduced in Stokes’ Memoir where he states that it was his wish to produce an Irish picture ‘somewhat historical in its object and poetical in its sentiment – a landscape composed of several of the monuments characteristic of the past history of our country, and which will soon cease to exist…’ (The story of pilgrimage in Ireland is well covered in Peter Harbison’s study (London 1991).

Petrie’s account of visiting pilgrims to Clonmacnoise is of interest:

‘The females of all ages, to whom uninquiring faith and enthusiastic devotion seem natural and characteristic; but, above, all, the young and beautiful girl, with pale face, blue eyes, long black eye-lashes, and dark hair, whose look betrays no conscious guilt, in the midst of her sighing prayers, but rather a feeling of love and devotion; who, notwithstanding her religious duties, is not so entirely unconscious of the power of her beauty, but that she can spare an occasional glance towards the strangers who are endeavouring to fix her figure on their paper or on their memories – a figure, as a friend well observed, that no one but Raphael could draw.’ Petrie (see below)

It will be seen from the above outline, that the scenery of Clonmacnoise is of a character altogether lonely, sublime, and poetic. These qualities are rather enhanced than abated by the appearance of the figures usually found here, and which are so identified in character with the ruins that they may be truly said to belong to each other. These figures are of pilgrims who come hither from various and frequently the most remote parts of Ireland, to court the favour or avert the displeasure of God by a long and painful penance. Their simple costumes, of every varied colour, give animation to the landscape, while the character of their countenances presents subjects for observation of the deepest interest.

They consist chiefly of females and men of middle age, in whose physiognomies the indications of intense devotion or despairing guilt are often strongly defined. Characters of a more pleasing kind, however, are by no means uncommon. The anxious mother may be seen endeavouring to procure health for her decaying child; the blind and decrepit to obtain deliverance from their ailments; the unfortunate to obtain a cessation of their afflictions; and the aged, with their white locks floating on the wind, shortening their road to a better world by a toilsome penance in this. Their attitudes too, and the situations in which they are grouped, are often in the highest degree picturesque and striking. Sometimes kneeling or prostrated round a grassy hollow – the ruins of some holy shrine; at other times creeping on their bare knees to some place of still higher sanctity; now arranged in silent prayer round the rude bur gorgeously sculptured stone cross, which they afterwards kiss with the utmost fervency of devotion; and now, hurrying rapidly along to some more distant object of worship. In all their movements there is an abstracted intensity of feeling that carries the mind back to remote times, and a rapturous expression of devotion and holy love may occasionally be observed, which a philosophic observer might, perhaps, envy or wish to participate in. The casualties of season or weather are wholly disregarded, and the observations of strangers unnoticed. Figures of a higher rank and less picturesque costume seldom appear here, and such indeed I have seen but once. They were a lady and her two daughters, habited in elegant mourning dresses, who entering the graveyard with hurried step, advanced to a tomb of recent erection, round which they knelt in silent prayer for an hour or two, while the tears which flowed continually down their cheeks showed the intensity of the sorrow which brought them hither. After they had retired, I had the curiosity to examine to whom the monument had been raised. He was a gentleman of the name of Coghlan, a descendant of the ancient princes of the country.

Such are the figures usually to be seen, among the ruins of Clonmacnoise. Few days, however, pass over, in which it does not, for a while, present a scene of wild commotion, when the silent solitude is disturbed by the ulligaun or death-cry, raised as some peasant of the country is borne to the grave of his ancestors. On those occasions the sorrowing kindred of those interred here, give full vent to their excited feelings of grief and affection at sight of their graves, throwing themselves on the grassy hillocks, which they kiss and press with melancholy ardour, now praying fervently, and now making the most distressing lamentations. These noisy, temporary visitors are not less in character with the place than the silent pilgrims who usually haunt this desolate ruin. Both alike come for those purposes that brought others here for more than a thousand years, with the same customs and ceremonies, the same lamentations and death-cry, and the same peculiar and intense feelings. Then, indeed, when the ulligaun was raised, it was for some person of the highest rank or glory, and among the pilgrims might be seen the richly-adorned figures of princes leaving their caps and sandals at the church door [32], and, with staff in hand, performing the routine of penances now only the duty of the peasant.

But Clonmacnoise herself was then proud and splendid, the bells of her lofty towers were heard with joy by the distant traveller, and her temples, shaded by the solemn gloom of the sacred grove, resounded to the eternal praises of the living God. The figures seen here on those found now, which, like the falling temples they wander amongst, and the dead and dying trees that shade them, all equally belong to other times and other feelings.

The number of pilgrims who came annually to perform at Clonmacnoise was, even to a recent period, very great; but their number is daily declining – so much so indeed, that on a recent visit here we have passed a whole day without seeing one. What can be conceived more solitary than Clonmacnoise at such times! It is in scenes like these that the social habits of man’s former greatness strikes the imagination with a greater sense of loneliness than the most dreary mountain solitude.

The appearance of a canoe on the silent stream, or a fisherman – a little speck on the river’s bank – or a fowler pushing his boat through the long rushes in pursuit of the wild birds that make such solitudes their homes, these have been marked by us at Clonmacnoise with pleasing interest; and the loud sounds of the boatman’s paddles, the disappearance of the fisherman, or the discontinuance of the sportsman’s shots, have excited a feeling of regret that we should have hardly supposed possible but for such experiences.’

To the student of Irish history there is not a less more striking or more sad than may be drawn from the state of desecration of our ancient churches and places of sepulture. Without and within the abbey walls, neglect and confusion are everywhere apparent. The church is often a shelter for cattle, while noisome weeds grow through the confused mass of broken tombstones. From a natural clinging to the sanctity of the place, the poor peasant seeks to inter the remains of those he loved within the walls of the old church, ruined though they may be. Old graves are thus violated, and heaps of skulls and whitened bones fill the corners of the building. This is no exaggerated picture, as they will find who visit many of the ruined abbeys of Ireland, of which the remains still exist to tell the story of centuries of violence, confiscation, and decay.

On this feature of the country, Petrie, alluding in his journal to the condition of the ruins of Clonmacnoise, thus he wrote almost 200 years ago:-

[33] The graveyard has ever been held sacred to pensive meditation and to moral thought. It is there that the tears of the child, which the cares and the pleasures of life have dried up, burst forth as fresh for the parent whose beloved voice can never in this world be heard again. Thither the good repair, to offer their tribute at the shrine of departed excellence, and the lover of liberty and truth, to give honour to the noble and virtuous. In such a place none but the best feelings of our nature are called forth; and he must be base indeed who can depart from the solemn abode of death without being excited to useful thought, and feeling a wish that he had been, or might yet be, a better man. Hence the pious care that the tomb has ever received among civilized communities; and there cannot be a more striking proof given of the want of proud and honourable feeling, or the excess of national debasement, than in this reckless indifference to the sacred monuments of the dead. ‘ ‘

[94] There is not, perhaps, in Europe where the feeling heart would find more matter for melancholy reflection than among the ancient churches of Clonmacnoise. Its ruined buildings call forth national associations and ideas. They remind us of the arts and literature, the piety and humanity which distinguished their time, and are the work of a people, who in a dark age, marched among the foremost on the road to life and civilization, but who were unfortunately checked and barbarised by those who were journeying on the same course and ought to have cheered them on.

Petrie’s cry was echoed many times since the 1820s in connection with Clonmacnoise. It was not until 1955 that the cemetery was taken in charge by the Office of Public Works. In 1993 a new interpretative centre was opened to preserve and display the highlights of the artistic remains at Clonmacnoise. That was over thirty years ago and renewal and revision is needed. The Durrow monastic site and Clareen should be part of any package of improvements so as to allow more visitors while spreading the burden.

Sources for the DIB entry

General Register Office (death cert.); Charles Graves, ‘Address on the loss sustained by archaeological science in the death of George Petrie, LL.D.’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, ix (1867), 325–36; William Stokes, The life and labours in art and archaeology of George Petrie (1868); Strickland; Alfred Perceval Graves, Irish literary and musical studies (1913); Grace Calder, George Petrie and the ancient music of Ireland (1968); Aloys Fleischmann, ‘Petrie’s contribution to Irish music’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, lxxii, C (1972), 195–218; Joseph Raftery, ‘George Petrie, 1789–1866: a re-assessment’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, lxxii, C (1972), 153–7; John Andrews, A paper landscape: the ordnance survey in nineteenth-century Ireland (1975); Marian Deasy, ‘New edition of the airs and dance tunes from the music manuscripts of George Petrie, LL.D., and a survey of his work as a collector of Irish folk music’ (Ph.D. thesis, National University of Ireland, University College Dublin, 1982); David Cooper, ‘George Petrie’, Stanley Sadie (ed.), The new Grove dictionary of music and musicians (2nd ed., 2001); David Cooper (ed.), The Petrie collection of the ancient music of Ireland (2002).

See also Peter Murray, George Petrie (1790–1866): the rediscovery of Ireland’s past (Gandon Press for Crawford Gallery, Cork, 2004).

Feehan, King, Manning, Tubridy and more studies can be viewed at the Offaly History Collection on www.offalyhistory.com and go to library.

Many of these books can be viewed in the library of Offaly History at Bury Quay, Tullamore. You will be welcome to call.

One last point why not make the proposed revamp of Clonmacnoise Visitor Centre more ambitious and honour Petrie and others

[1] Peter Murray, George Petrie (1790–1866): the rediscovery of Ireland’s past (Gandon Press for Crawford Gallery, Cork, 2004). Copies available at Offaly History Centre to view or buy.

[2] Petrie’s first impressions of Clonmacnoise from William Stokes, The Life and Labours in Art and Archaeology of George Petrie, (London 1868), pp 27-33.

This series is supported by Offaly County Council’s Creative Ireland community grant programme 2025-2027.