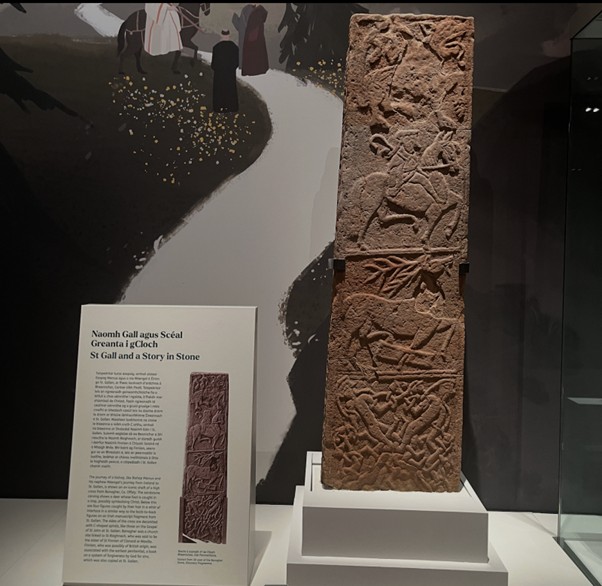

MUSEUM CAPTION :‘In preparation for our major temporary exhibition Words on the Wave: Ireland and St. Gallen in Early Medieval Europe, opening in late May this year, we reveal the ongoing conservation and scanning work on the famous high cross shaft from Banagher, Co. Offaly (1929:1497). The cross helps tell the story of the connections between art, belief and society in the world which produced the manuscripts.

‘The journey of a bishop, like Bishop Marcus and his nephew Moéngal’s journey from Ireland to St. Gallen, is shown on an iconic shaft of a high cross from Banagher, Co. Offaly. The sandstone carving shows a deer whose foot is caught in a trap, possibly symbolising Christ. Below this are four figures caught by their hair in a whirl of interlace in a similar way to the back-to-back figures on an Irish manuscript fragment from St. Gallen. The sides of the cross are decorated with C-shaped spirals, like those on the Gospel of St. John at St. Gallen. Banagher was a church site linked to St. Ríoghnach, who was said to be the sister of St. Finnian of Clonard or Movilla. Finnian, who was possibly of British origin, was associated with the earliest penitential, a book on a system of forgiveness by God for sins, which was also copied at St. Gallen.’

THOMAS LALOR COOKE FINDS BANAGHER CROSS IN THE MONASTIC GRAVEYARD

Cooke, Thomas Lalor (1792–1869),Birr, attorney and antiquarian.

‘On a fine summer day, many years ago, loitering about the straggling, long, and unpicturesque street of Banagher, I happened to ramble into this church-yard, as well with a view to beguile time as for the purpose of examining any relics of antiquity which might there present themselves. The trouble of the visit was amply compensated; for I there found, prostrate on the earth, a stone, of which I send a sketch with this paper, showing it as it then was. In using the words “it then was” I do so emphatically, in order to contrast its then with its present condition; for the stone has since that time been sadly and wantonly damaged. (Written in May 1859)’

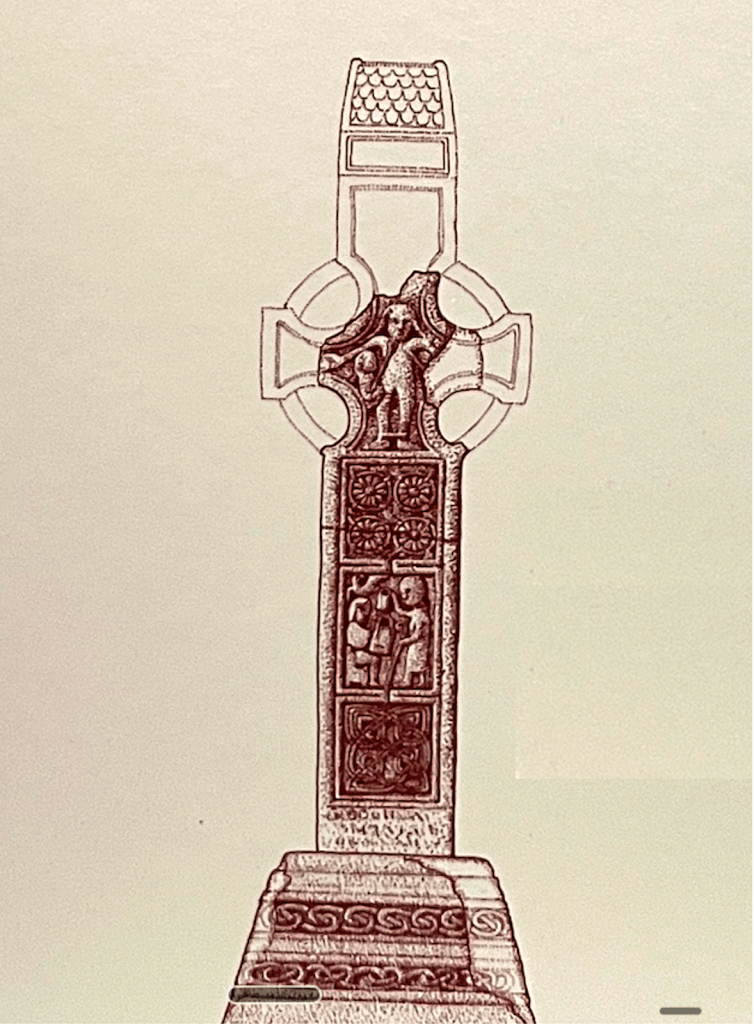

Dating to around 800AD, this decorated stone cross shaft is an example of the type of art used on stone, metalwork and manuscripts in this period often known as the Golden Age of Irish Art. The cross is 1.47m tall, and its tapering faces and sides have maximum dimensions of 40cm and 19cm respectively. All the corners have small roll moulding, and the panels which are all of different sizes are also framed by similar moulding.

BANAGHER CROSS ON THE MAPS

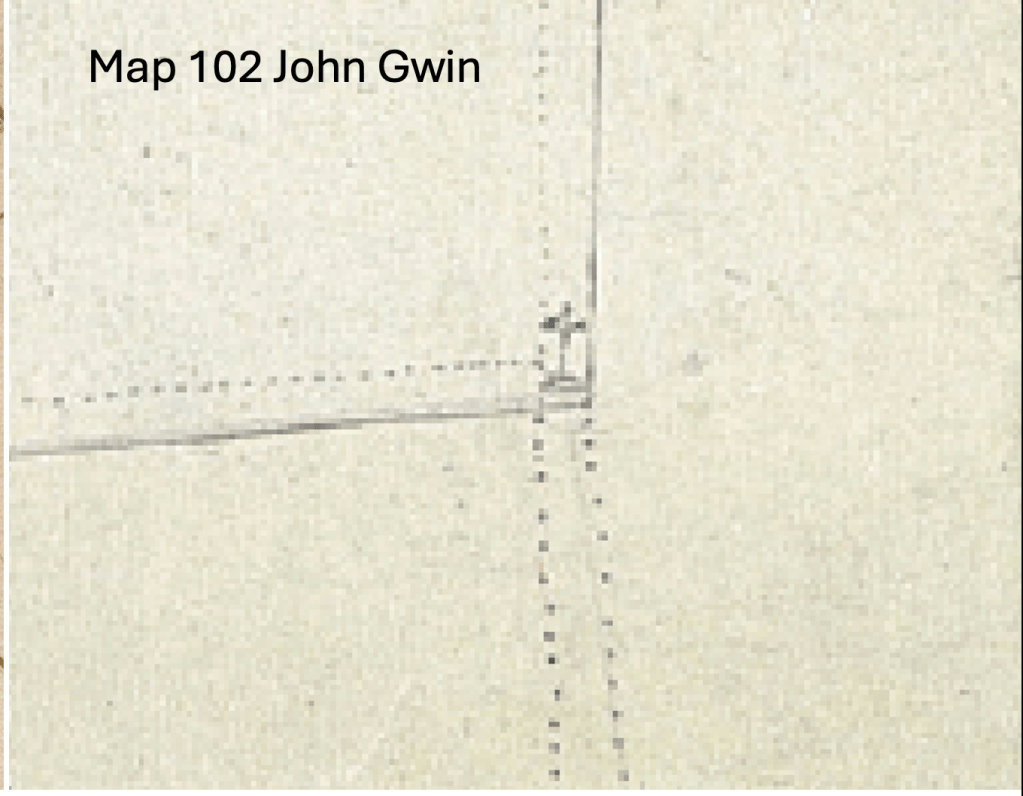

Map MPF 1/102, by surveyor John Gwin, shows the cross as being cruciform and located on the middle of the road.

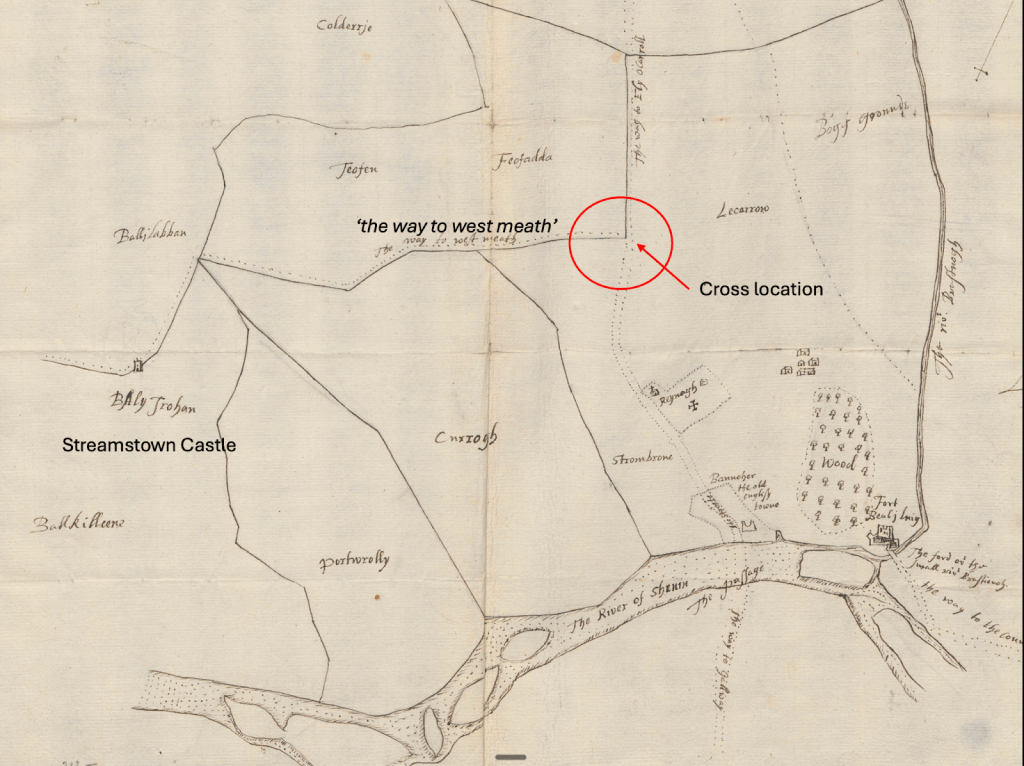

We are extraordinarily fortunate that the Banagher Cross appears on four of the De Renzy’s maps drawn almost exactly four hundred years ago. Without them, its original location would be lost to us. The fact that the surveyors marked the cross at the junction leading into the town is telling. It shows that in the 1620s the cross was still a recognised landmark, important enough to be fixed in the cartographic record alongside streets and burgess plots.

Its presence on those maps also makes a statement about Banagher itself. At a time when the town was being reshaped as a plantation borough, the survival of a medieval cross at its centre symbolised continuity as well as change. The maps inadvertently captured both: the new civic grid of an English borough, and the enduring presence of an ancient Christian monument.

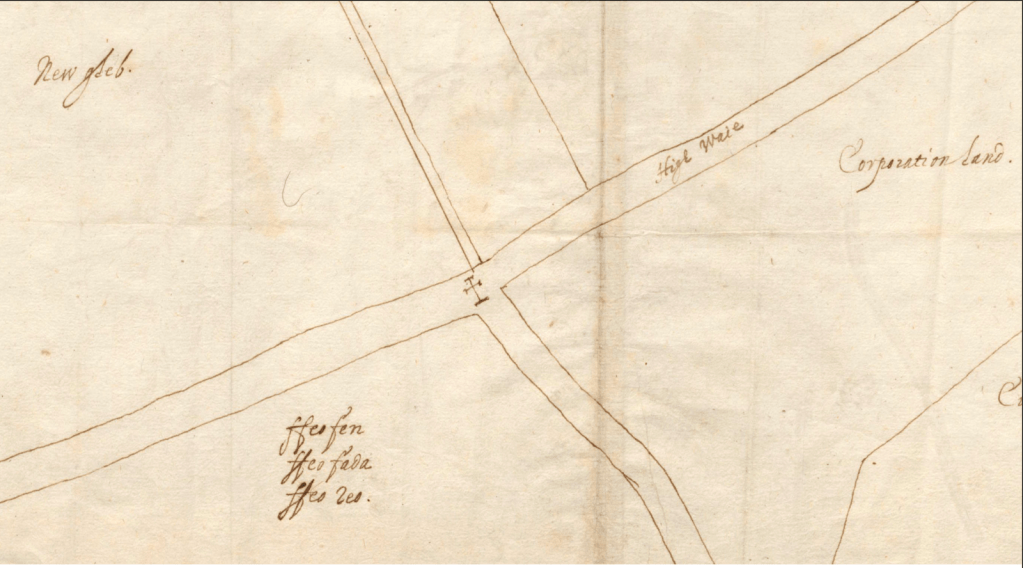

Banagher: New Corporation town layout 1628

There are about thirty maps in the De Renzy collection of maps in the National Archives, Kew, London. Eight of the maps are in the hand of Matthew De Renzy, four of which show the layout of the new Corporation town of Banagher and two of these show Banagher Cross and its location which was at the junction of St Rynaghs road and Banagher-Birr road.(adjacent to St Pauls Church)

Map SP49-91, drawn by surveyor, John Gwin, shows ‘the way to west meath’, the main road out of Banagher to Athlone and Dublin c.1630. The road went by the modern graveyard and then through Baliver.

Map MPF 268-248 in the hand of Matthew De Renzy confirms the location of the cross and its relationship to the townland of Feeghs which still exists today.

‘Ffeofen, ffeofada, ffeoreo’

These three terms all derive from feo- (Irish for “beech”) with suffixes distinguishing variety: Feofen for the common beech, Feofada for the tall straight-stemmed beech, and Feoreo for the red or copper beech. They show how Irish writers classified tree types with striking precision long before modern botany

The remains of Banagher Cross is described as a shaft or a pillar. But it was cruciform and might have looked likeTihilly High Cross above.

MUSEUM:

‘In 9th-century Ireland, stone crosses marked the boundaries of church enclosures. Like manuscripts, these monuments showed scenes from the Bible and were decorated with the same art motifs found in books and on metalwork. The stone caps from these crosses were shaped like contemporary wooden and stone churches and had similarities with metal shrines. The Tihilly, Co. Offaly, cross illustrated the story of Adam and Eve and of the Crucifixion. It belongs to a well-known group of high crosses in the Irish midlands and the way figures are arranged is very similar to that in the Irish Gospels of St Gall.’

MAKING A REPLICA OF THE 8TH CENTURY CROSS

The Discovery Programme scanned the Banagher Cross Shaft (1929:1497) creating a 3D model ( see link Banagher Cross 3d image)

This digital record opens up remarkable possibilities. Using the scan, a full-size replica could be produced by first 3D-printing the shaft in plastic, then making a fibreglass mould, and finally casting it in concrete. Easier said than done — several attempts might be needed — but the result would be an extraordinary project, one that certainly would not “Beat Banagher.”

Offaly County Council may even have anticipated such an idea. The traffic-calming island built directly outside St Paul’s Church provides a ready-made site — and it happens to be exactly where the cross stood for centuries. To restore a replica of the Banagher Cross to its original location would reconnect the town with its medieval landmark and bring history back into the heart of the streetscape.