The Murals Bar Cultural life in 1950s Tullamore centred around ‘The Murals’ bar. This was where us local artists, actors, historians and writers drank, clutching our copies of ‘Ulysses’ in its concealing brown paper cover while engaging in fevered and sparkling debates on cubism, existentialism, atonality and Marxism.

I may be exaggerating somewhat, but ‘The Murals’ really was our Deux Magots, our Cafe de Flore. The bar was the meeting place of what passed for an intelligentsia in Tullamore at a time, which, though it is now regarded as restrictive and obscurantist, I remember as stimulating and progressive. Maybe I was lucky.

The attraction of ‘The Murals’ was its design which was quite unlike any of the more traditional pubs of the town which were usually small, dark and poky. With its high ceiling, stripped down design, timber veneering, bright red stools, it was cool and elegant and above all- modern.

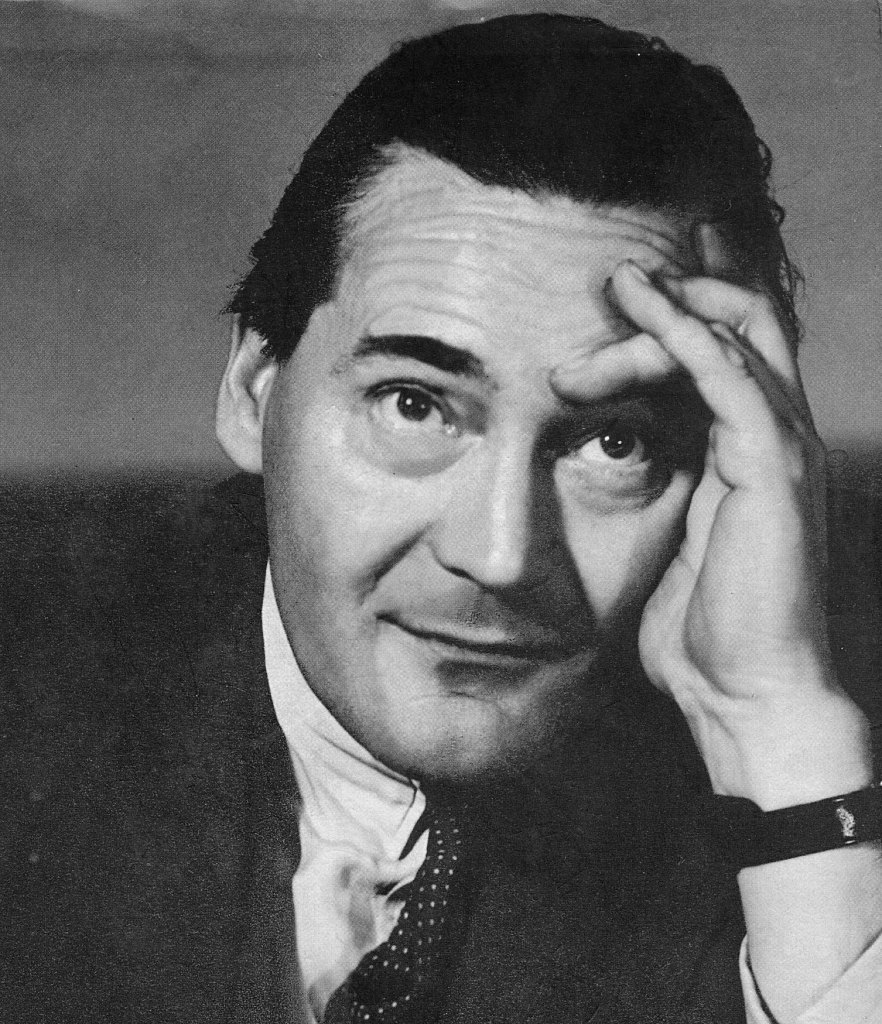

What really contributed to its sophisticated atmosphere however was the extraordinary mural by Sean O’Sullivan depicting a joyous tipsy Connemara wedding which ran all the way around the walls. In the centre of the composition, clad in a báinín jacket and dancing with the pretty barmaid, was the creator of our favourite haunt, its architect Michael Scott. (illus.)

Scott and the Midlands

Scott had burst upon the Midlands with the Modernist County Hospital which he had designed in association with Norman Good between 1934 and 1942. Its dramatic design and particularly its innovative use of local Ballyduff limestone had made a strong impression locally.

And besides being the first Modernist building to be erected in the Midlands, the Hospital also contained the first example of mildly progressive art to be offered in a public setting, The Legend of St. Columcille’ which was quite unlike any other Irish religious art of the period. The work had been commissioned by Scott from Frances Kelly – later known as Judy Boland and mother of the poet Eavan Boland-who had been a student with him in the National College of Art. Sadly, this wonderful building and its charming painting is no longer publicly accessible.

Following on the Hospital’s success Scott won other public work in the Midlands including the Vocational School in Clonaslee and a housing scheme at The Hill in Banagher and this was followed by private commissions.

In the early 1940s Desmond Williams, the go-ahead director of D.E. Williams, whose commercial interests stretched across the Midlands and included a distillery, maltings and pubs and shops in every town and village, married the beautiful Brenda Gogarty, the daughter of Scott’s friend Oliver St. John Gogarty and who had been painted by Augustus John.

In 1945 as a wedding present for Desmond and Brenda, Scott designed a fine new house ‘Sheperds Wood’ outside of Tullamore (Illus).

Give Every Man His Dew

Despite the straitened times of ‘The Emergency’, Desmond Williams’s company D.E. Williams (whose motto ‘Give Every Man his DEW’ was well known at the time) embarked on an ambitious programme of renovating many of the company’s shops and pubs in Offaly, Laois and Westmeath.

The commission was given to Scott who responded by creating an architectural style deriving from the detailing of the County Hospital project but featuring facing panels of local Clonaslee buff sandstone enclosed within horizontal banding which became unique to the Williams brand and was used in all their retail outlets. Its finest example was the renewal of Williams flagship shop and offices in Patrick Street, Tullamore, (Illus.) which included ‘The Murals’ bar.

The decoration of pubs and restaurants by notable Irish artists was very much a fashion in this period as may yet be seen in the murals by Cecil French Salkeld in ‘Davy Byrnes’ in South Anne Street in Dublin, while Frances Kelly had decorated the walls of the fashionable Russell Hotel on Stephens Green. In Williams’s bars in Athlone and ‘The Murals’ in Tullamore, Scott commissioned his friends Louis le Brocquy and Sean O’ Sullivan to provide art works

Le Brocquy delivered a fresco in the Athlone bar which I recollect as being dark, obscure and gloomy and not a very appropriate backdrop to a pleasant drink. It seemed to have been based on vaguely mythological figures not unlike those in his later ‘Tain’ series. There may also have been references to the hieroglyphs on the ancient and mysterious Clonfanlough stone some miles away.

O’Sullivan’s bar room panorama on the other hand was joyous, celebratory and, most importantly, artistically unchallenging. Many of the figures used local characters as models and in the corner O’Sullivan depicted himself recording the festivities.

While executing the Athlone fresco, le Brocquy stayed with the Williams family and became fascinated by the lifestyle of a Traveller family he encountered just outside Tullamore. They became the inspiration for one of his greatest paintings ‘Tinkers Resting’ (Illus.), 1946 which is now in the Tate Gallery, London.

The Jesuit Chapel, Tullabeg, Tullamore

The Williams family were close friends of the Rector of the Jesuit Seminary at Tullabeg in nearby Rahan, Fr Donal O’Sullivan S.J. At this time there was an informal connection between Desmond Williams, who had a magnificent collection of Modernist paintings, and Fr O’Sullivan and the Earl of Rosse, both of whom served together on the Arts Council. This resulted in several exciting exhibitions in Tullamore centering around An Tostal and supported by the commercial Dublin galleries and which brought works by Yeats, George Campbell, Patrick Scott, Nano Reid and particularly Jack B. Yeats to young impressionable minds including my own.

Presumably it was this connection also which prompted Fr Donal to commission Scott (who waived any fees) to convert the Jesuit Seminary chapel to a private oratory.

The nature of the commission gave Scott a freer hand than might have been ordinarily available regarding ecclesiastical art and design in that very conservative period and he created a simple, small, calm space with four windows along one side and one at the end which was then adorned by exquisite sculpture and stained glass.

When the question of who would design the windows arose, Fr Donal suggested the studio of Harry Clarke which, even though Clarke was long dead, had flourished on work from the Order. Scott however favoured Evie Hone and this suggestion was inspired as she and Fr. Donal struck up a friendship when they met. The magnificent Tullabeg windows, now in Manresa College in Dublin, are regarded, after her window in Eton College Chapel, as amongst Hone’s finest works.

Opposite the single window in a small apse, the sculptor Laurence Campbell provided a carved timber altar now in Mucklagh Church and a statue of the Madonna and St Ignatius whose present whereabouts are unknown.

Around the walls were a series of circular terracotta Stations of the Cross by the French sculptor Robert Villiers. These were later removed and it is unclear whether those in St. John’s Church of Ireland in Sandymount, Dublin or Durrow Church outside Tullamore are the originals or copies.

The chapel opened in 1946 and as its nature and decoration were in such contrast to the traditional approach to church design of the time it soon became a model for artists and architects of advanced views.

Sic Transit

None of Scott’s wonderful Midland works survived fully intact.

The Murals Bar and its O’Sullivan panorama vanished in the 1980s. The le Brocquy fresco in Athlone was long gone by then. ‘Shepherds Wood’, like his County Hospital, was altered almost beyond recognition. The Tullabeg Chapel was closed and the works dispersed. All of the shops and bars in Kilcormac, Clonaslee, Portarlington vanished. O’Donoghue’s Bar in Edenderry may be the sole unaltered (but as yet unattributable) work. The County Hospital was converted to offices and Kelly’s mural hidden from public gaze.

Only one pure work remains to this day- the delightful bungalow in Tullamore which he designed in the 1950s for Florence Williams (Illus.) It was the last design to be executed in the distinctive vernacular style exclusive to the family. Regrettably and surprisingly, it is not a Protected Structure.

A Grand Opening

I met Michael Scott twice. The first occasion was in Groome’s Hotel opposite the Gate Theatre. With its eclectic political, literary and theatrical clientele, Groome’s replicated the bohemian atmosphere of the Murals .

Sometime in the late 1960s I spotted him in the rear lounge, the centre of a group of well-known actors and politicians. I shyly approached, introduced myself as an architect and mentioned that my current studies in town planning had been inspired by an article on the design of provincial towns he had written in The Bell in the 1950s. He was initially receptive but when he discovered that I was also from Tullamore, I received the full Scott charm.

We went and sat together in a side alcove with our drinks and he reminisced about his Offaly days, his various works, his friendship with the Williamses and the Egans and in particular enquired about the famous seven pretty daughters of his friend Dr. Brady of Kilcormac with whom he often stayed on his Midland site visits. After a few drinks we parted but promised to keep in touch.

In 1971, John Ryan the writer, broadcaster, artist, publisher and formerly the owner of ‘The Bailey’ in Duke Street and who now had a gallery in Monkstown above the fashion shop run by his wife Dee, offered to host an exhibition of my architectural sketches. When we discussed who might open it, both of us nominated Michael straightaway.

On the night of the show, the room was packed but no sign of Michael. About an hour late he arrived with Fr Donal and it was pretty obvious that they had had a good lunch which had continued on. Nonetheless, he worked the room and charmed the pants off everyone. He then proceeded to launch my show.

After a few flattering but shrewd comments on my drawings, he observed that he had looked forward very much to this, my first Dublin exhibition. He had taken a close interest in my work over the years and went on to mention our Offaly connections – indeed, he thought it possible that we might be distantly related. He then declared;

‘I would now like to open this show of drawings by my dear friend……. Fergal Mac Grath’

I forgave him. You couldn’t but.

Our thanks to Fergal MacCabe for this important article. Pics and captions mostly Offaly History.

This series is supported by Offaly County Council’s Creative Ireland community grant programme 2025-2027.