David Beers Quinn’s collaboration and lifelong friendship with Robert Dudley Edwards is described in Telling the Truth is Dangerous, one of the first biographies of a modern Irish historian. Author Neasa MacErlean, Edwards’s granddaughter, looks at a relationship that helped modernise the study of Irish history.

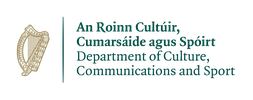

The third revolutionary: David Quinn

The ‘scientific revolution’ in Irish history is generally seen as the brainchild of two professors but, in fact, there were three. David Beers Quinn was the third who, with Robert Dudley Edwards of UCD and Theo Moody of Trinity, established the professional basis for the study of the subject which remains in place today.

It was as 22- and 23-year-olds that the trio met in the early 1930s, setting out on the rare step those days to take a PhD. This was at London University’s Institute of Historical Research — almost a necessity for those ambitious young men because the Irish documents they wished to examine had been burnt in the Four Courts in 1922, while copies remained available in the British Library. It was in Bloomsbury and the West End that Edwards and Moody, who lodged together, framed their ‘agenda for history’, and this was shared with their new friend Quinn when he became the third Irishman to enrol in the institute in 1931.

Although a lifelong dedication to history drew the small group together, they were also remarkably similar in a variety of ways. All were Tudor-Stuart specialists — with the focus of their doctorates giving indications of their niches within that sector.* They married women with whom they collaborated on their work, and whom they regarded as their intellectual equals (or even superiors). Quakerism had a profound effect on each, even if Moody was the only one who joined the Society of Friends. (This link and its implications are examined in an article in the July/August 2025 issue of History Ireland.) The long hours they laboured reflected a love for the subject rather than workaholism. All three were committed to public history, presenting the subject to the population at large (including people with little formal education). So in tune were their minds that each could explain what the others wrote, starting with the doctoral theses.

When in 1938 Edwards and Moody established Irish Historical Studies (now in its 88th year), Quinn was one of its most regular contributors. This journal was a foundation stone for the modernised profession of historians, who could compare notes and publish in IHS, read its research lists and avoid reinventing wheels. Equivalent moves were made across the whole ambit of writing and teaching history — including setting research standards, running conferences to share ideas and collaborating with historians abroad. Aware that they were changing the nature of study, they noted down many significant moves made by the others. In 1942, Quinn found himself ‘plunged into the Moody–Edwards vortex’, describing Edwards at a meeting in Belfast as being ‘his most forceful and successful self, planning postwar events at a time when the end to the international struggle was not visible’. In December 1957 Quinn and Edwards had lunch, after which the latter noted in his diary: ‘He has a lightness of touch which is far more interesting than the increasing stodginess of other chums of London days. He so far stands above Rouse [AL Rouse, the leading British Tudor historian] that he matched my criticism of the need to see colonisation as a European phenomenon [and went on] to say that he planned a book on all the voyages from Columbus.’ And it was in this field that Quinn researched and laid the ground for others over the rest of his career.

Professors of history operating at high levels have to be careful in whom they confide but Quinn and Edwards could do this, as their later comments relate. Quinn described visits from the UCD professor to his home in Liverpool where he also held a chair in history. ‘He and I would get involved in complex academic discussion, but my wife, Alison, could intervene to spark off a different side of him, the racy anecdotal raconteur, witty, all-knowing, often satirical, an area in which he was a master. We have rarely enjoyed anything more.’ Writing formally in his book Sources for early Irish modern history (co-authored with Mary O’Dowd), Edwards evaluated his contemporaries, saying: ‘Although Professors Moody and Edwards did publish sporadically in this field, their teaching and editorial interests led them into more recent periods of Irish history…Professor Quinn’s published contribution to the history of early modern Ireland is undoubtedly the most outstanding of his generation.’ Not only were they remarkable historians in their time but they recognised that the advances they made could also become history one day. And now that time has come.

Book details

Neasa MacErlean, Telling the Truth is Dangerous — How Robert Dudley Edwards changed Irish History forever

Published by Tartaruga Books (part of Not Only Words), published 23 June 2025. £11.99pb, 288 pp,

ISBNs:

Printed book — 978-1-83952-917-7

E-Book — 978-1-83952-918-4

More information on https://notonlywords.co.uk/tellingthetruth

Launches

Dublin, at Hodges Figgis, Dawson St, on on Thursday, 26 June at 6pm

Galway, at Charley Byrne’s bookshop, Middle St, on Friday, 27 June at 6pm

All are welcome to the launches, where refreshments will be served.

Also see and earlier blog in this series on DB Quinn and Vivian Mercier by the late Sylvia Turner.

Supported by the Department of Culture Communications and Sport as part of the Commemorations Series for 2025.