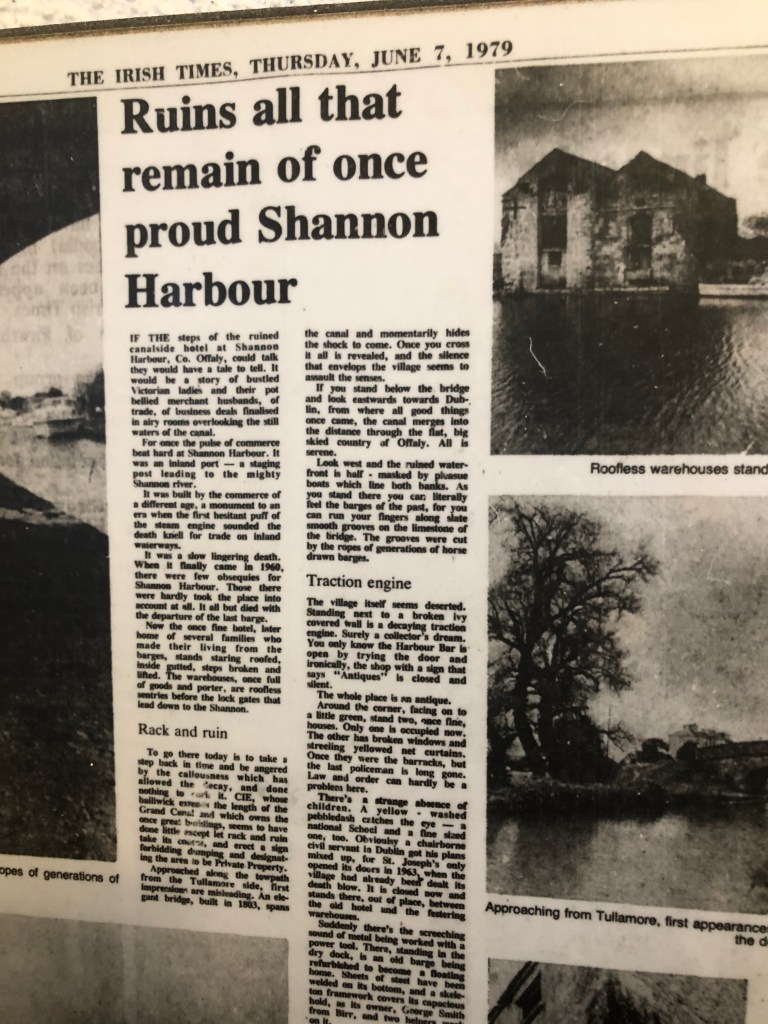

The Grand Canal was completed to the River Shannon in 1804, 220 years ago. By 1864 passenger traffic was finished and commercial by 1960. Cruise traffic was only in its infancy and when this article was written 45 years ago things were bleak. In looking at the building of the Grand Canal from Tullamore to Shannon Harbour, we need to look at a piece written in the Irish Times by Sean Olson with photographs by Pat Langan, which was published on Thursday, 7 June 1979 in the Irish Times. The newspaper had been a good supporter of keeping the canal open in the 1960s when it was under threat from Dublin Corporation.

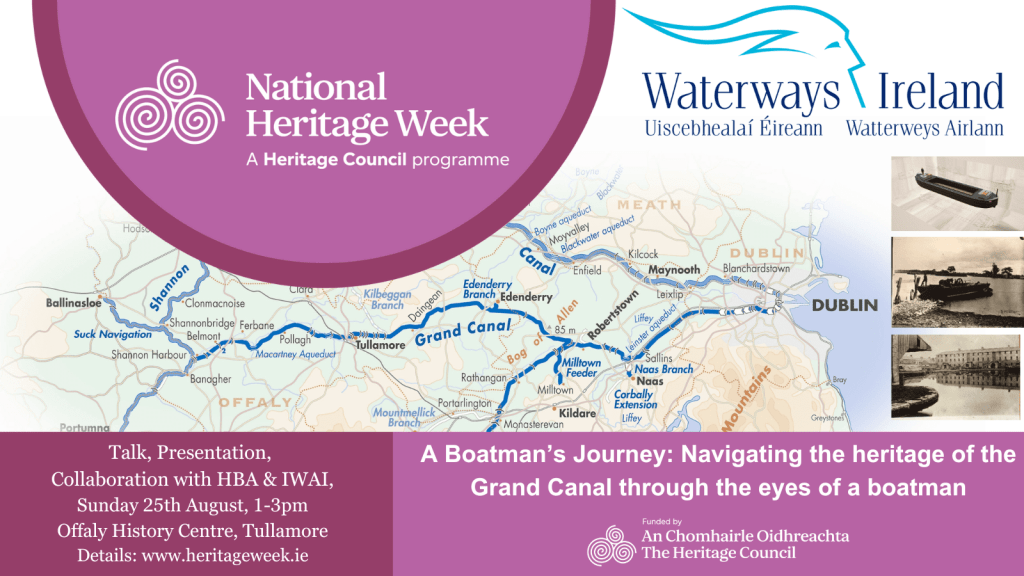

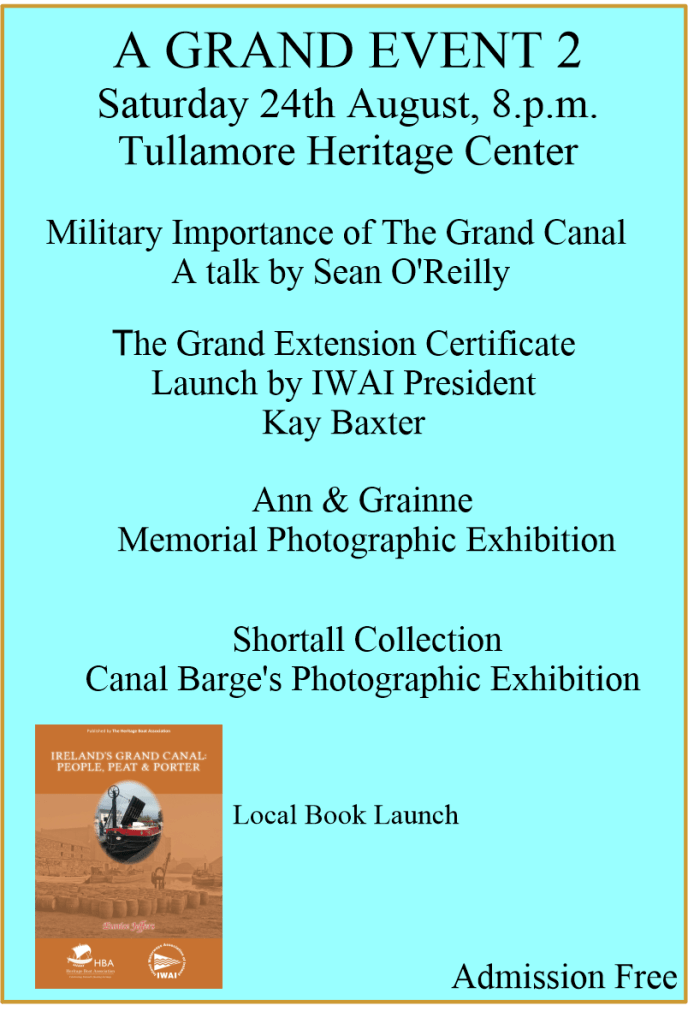

Things have improved so much in recent years with the towpaths now the focus of attention to promote walking and cycling. Today 23 August see the launch of an excellent study of the canal system as illustrated. Then on Saturday evening and Sunday there are two events from Waterways Ireland to be held in the Offaly History Centre Exhibition Hall beside the canal at Bury Quay (neighbour to Old Warehouse Bar and Restaurant), as illustrated.

Olson is worth reproducing to remind us that we do not want to go back there and was an excellent record of its time. Also worth mentioning is our over 60 blog articles on the Grand Canal available as blogs at http://www.offalyhistory.com. All free to read and download.

‘If the steps of the ruined canalside hotel at Shannon Harbour, Co. Offaly could talk they would have a tale to tell. It would be a story of bustled Victorian ladies and their potb-bellied merchant husbands, of trade, of business deals finalised in airy rooms overlooking the still waters of the canal.

For once the pulse of commerce beat hard at Shannon Harbour. It was an inland port – a staging post leading to the mighty Shannon river. It was built by the commerce of a different age, a monument to an era when the first hesitant puff of the steam engine sounded the death knell for trade on inland waterways. It was a slow lingering death. When it finally came in 1960, there were few obsequies for Shannon Harbour. Those there were hardly took the place into account at all. It all but died with the departure of the last barge.

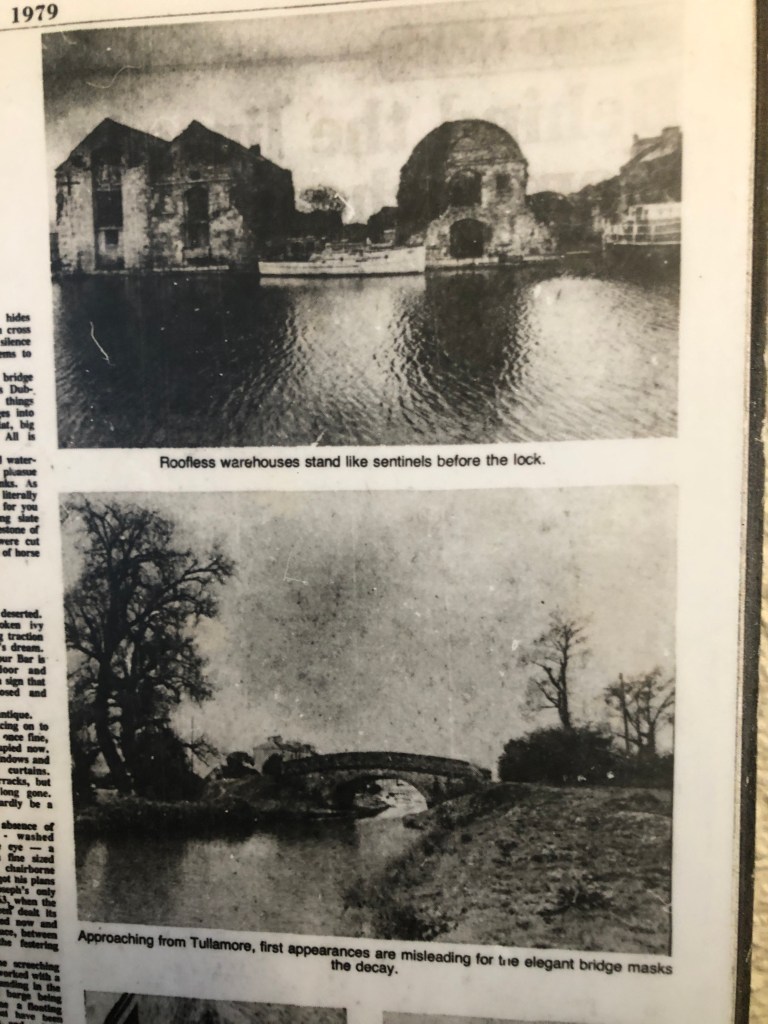

Now the once fine hotel, later home of several families who made their living from the barges, stands staring roofed, inside gutted, steps broken and lifted. The warehouses once full of goods and porter, are roofless sentries before the lock gates that lead down to the Shannon.

Rack and Ruin

To go there today is to take a step back in time and be angered by the callousness which has allowed the decay, and done nothing to curb it. CIE, (who owned the canal until 1986) whose bailiwick extends the length of the Grand Canal and which owns the once great buildings, seems to have done little except let rack and ruin takes its course, and erect a sign forbidding dumping and designating the area to be Private Property.

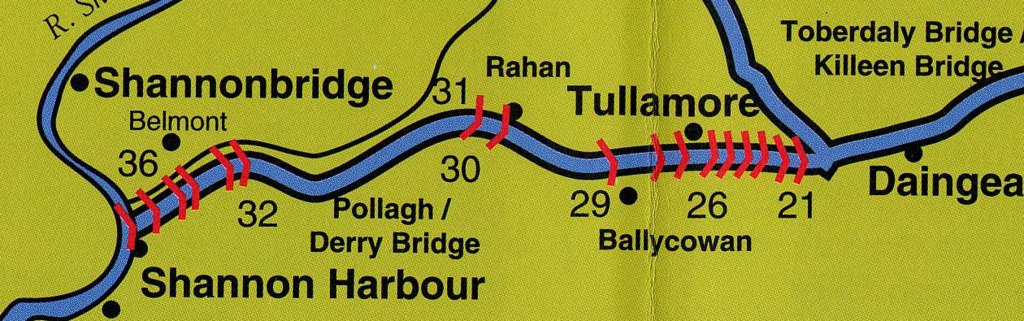

Approached along the towpath from the Tullamore side, first impressions are misleading. An elegant bridge, built in 1803, spans the canal and momentarily hides the shock to come. Once you cross all is revealed, and the silence that envelops the village seems to assault the senses. If you stand below the bridge and look eastwards towards Dublin, from where all good things once came, the canal merges into the distance through the flat, big, skied country of Offaly.

All is serene

Look west and the ruined waterfront is half-masked by pleasure boats which line both banks. As you stand there you can literally feel the barges of the past, for you can run your fingers along slate smooth groves on the limestone of the bridge. The grooves were cut by the ropes of generations of horse drawn barges.

Traction Engines

The village itself seems deserted. Standing next to a broken ivy-covered wall is a decaying traction engine. Surely a collector’s dream. You only know the Harbour Bar is open by trying the door and ironically, the shop with a sign that says ‘Antiques’ is closed and silent.

The whole place is an antique

Around the corner, facing on to a little green, stand two, once fine, houses. Only one is occupied now. The other has broken windows and streeling yellowed net curtains. Once they were the barracks, but the last policeman is long gone. Law and order can hardly be a problem here.

There’s a strange absence of children. A yellow-washed pebbledash catches the eye – a national School and a fine sized one, too. Obviously a chairborne civil servant got his plans mixed up, for St. Joseph’s only opened its doors in 1963 when the village had already been dealt its death blow. It is closed now and stands there, out of place, between the old hotel and the festering warehouses.

Suddenly there’s the screeching sound of metal being worked with a power tool. There, standing in the dry dock, is and old barge being refurbished to become a floating home. Sheets of steel have been welded on its bottom, and a skeleton framework covers it capacious hold, as its owner, George Smith from Birr, and two helpers work on it.

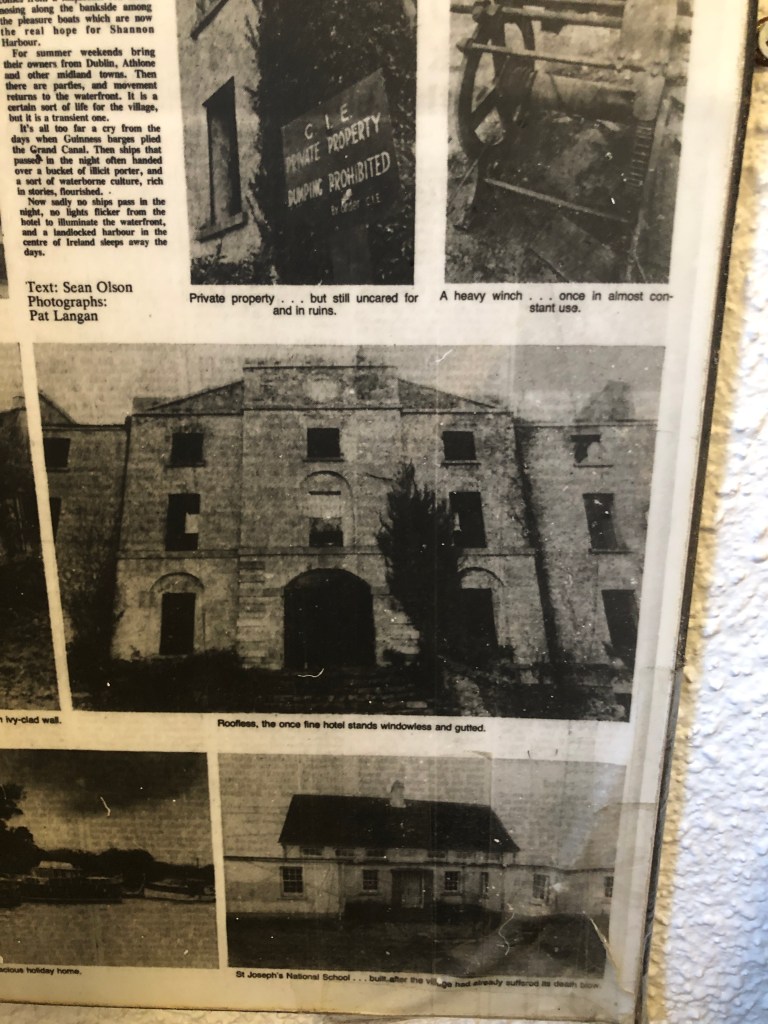

Pleasure Boats

The dry dock seems to be almost the focal point of life in the village. The only other movement comes from a handsome red setter nosing along the bankside among the pleasure boats which are now the real hope for Shannon Harbour.

For summer weekends bring their owners from Dublin, Athlone and other midland towns. Then there are parties, and movement returns to the waterfront. It is a certain sort of life for the village, but it is a transient one. It’s all too far a cry from the days when Guinness barges plied the Grand Canal. Then ships that passed in the night often handed over a bucket of illicit porter, and a sort of waterborne culture, rich in stories, flourished.

Now sadly no shops pass in the night, no lights flicker from the hotel to illuminate the waterfront, and a landlocked harbour in the centre of Ireland sleeps away the days.’ Thus Olson’s article concluded.

Today improvements are being made all along the Grand Canal system and its importance is fully appreciated. The pioneering work of Killaly, Rolt and IWAI was outstanding.