What we construct and what we take down is often the most significant indicator of the nature and health of our society. Also, the choice of an aesthetic style for a new building tells us much about the values of its proposer. Government or religious institutions will seek to emphasise their role and power by providing substantial and prominent structures, often using ancient architectural styles to suggest their continuity and permanence. Successful businesses or go-ahead institutions will express their vitality and cosmopolitanism in a more modern manner. Home builders may wish to attract respect for their taste and sophistication.

Architectural styles in the growth of Tullamore

In the period 1740 -1810 the new buildings and streets of Tullamore shared the well-mannered Classical Georgian style. The public and religious buildings in the years between 1830 and 1842 utilised Classical, Gothic and Tudor models while the styles of the great building boom at the beginning of the 20th century varied from the neoclassical of Egan’s and Scally’s emporia to the French Gothic of the Church of the Assumption.

However, the period between the late 1930s and the early 1960s is possibly the most interesting from the point of view of the architectural historian. The Modernist masterpiece of the County Hospital by Scott and Good and the iconic Clontarf Road terrace by Frank Gibney in the Arts and Crafts manner are its highlights, but six lesser buildings are worthy of recognition also.

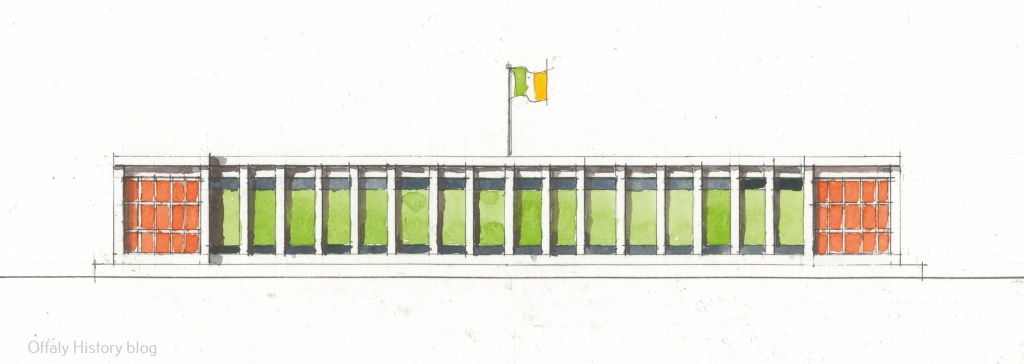

The Swimming Pool 1938

The generations who grew up between 1930 and 1990 remember the outdoor swimming pool at Cloncollog with great affection. For a modest entrance fee, young people and water sports enthusiasts enjoyed an outstanding sporting and social outlet.

As the first outdoor pool to be provided by an Irish local authority, it was fed by treated water from the adjoining river. Modelled on the Lidos appearing all over Europe at the time, it consisted of a single storey pavilion block which faced southwards onto a generous pool, shallow at one end and deep enough at the other to encourage high diving.

The design by the County Engineer T.S. Duggan, while strictly functional, was architecturally sophisticated and may be described as being a good example of the stripped-down Modernist style. Its enfilade of recessed changing rooms was bookended by two perfectly square advanced end blocks containing lockers. The whole composition and setting was a visual delight and its users, including the architect Yvonne Farrell, have testified to its formative impact on their aesthetic sensibilities.

Nonetheless, the open- air pool could not compete with the more modern indoor facilities which arrived at the end of the 20th century, and it was demolished.

Munster and Leinster Bank (now Allied Irish Bank), Colmcille Street 1950

The only new building of architectural merit (apart from Michael Scott’s subsequently altered Patrick Street shop for D.E Williams) to be built in the town centre in the mid-20th century, the Bank is also the last building in Tullamore to incorporate Neo Classical design features.

A well-mannered three storied composition with a strong projecting cornice, it conforms to the street line and to the height of the adjoining structures to the south. Composed of four bays, the southernmost is slightly advanced to incorporate an elegant entrance. Finished in finely dressed local limestone, the design incorporates a carefully detailed classical cornice above the ground floor. The interior is to the highest standard with a marble finished banking hall and an extremely commodious apartment for the manager and his family on the floors above.

The entire building exudes wealth, respectability, permanence, and reliability and reflects the prestige attaching to banks and bankers in that era. Its architect J.R.E. Boyd-Barrett (1904-1976) was one of the most prolific and successful designers of his generation. During nearly half a century in practice, he designed many notable buildings throughout the country including the Department of Industry and Commerce in Kildare Street, Dublin. In 1963 the Knighthood of the Order of St Sylvester was conferred upon him by Pope John XXIII for his services to ecclesiastical architecture.

Boyd-Barrett was also responsible for several other buildings in Tullamore amongst which is Scoil Muire (1957) in Kilcruttin with its delightful Art Deco doorway.

Despite their architectural qualities neither are Protected Structures.

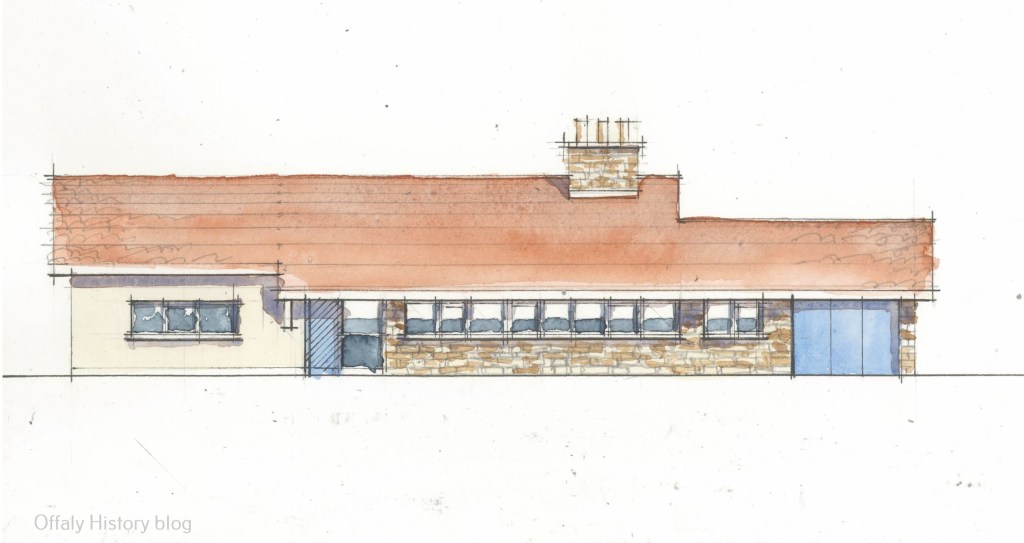

‘Ashleigh’ 1955

Built for Mrs Florence Williams, this bungalow was designed by Michael Scott, the most renowned Irish architect of his generation, who reverted to the palette of his 1940 DEW Head Office in Patrick Street of Clonaslee sandstone laid horizontally and enclosed within a strong white plaster surround.

Its architectural style of a long low roof with a running strip of windows below the eaves, lies somewhere between the ‘Prairie Style’ deriving from the houses of the great American architect Frank Lloyd Wright and features of the Arts and Crafts movement. The variation in levels of the ridge line and eaves delivers a distinctive profile while the contrast between the rough stone and smooth plaster provides textural delight.

Inspired by the templates of ‘Bungalow Bliss’ rural Ireland was to be blighted in the following years by houses which might have been somewhat better had the underlying design principles of ‘Ashleigh’ been understood and promoted.

Today, though ‘Ashleigh’ is the only intact building by Scott remaining in Offaly, it is not a Protected Structure.

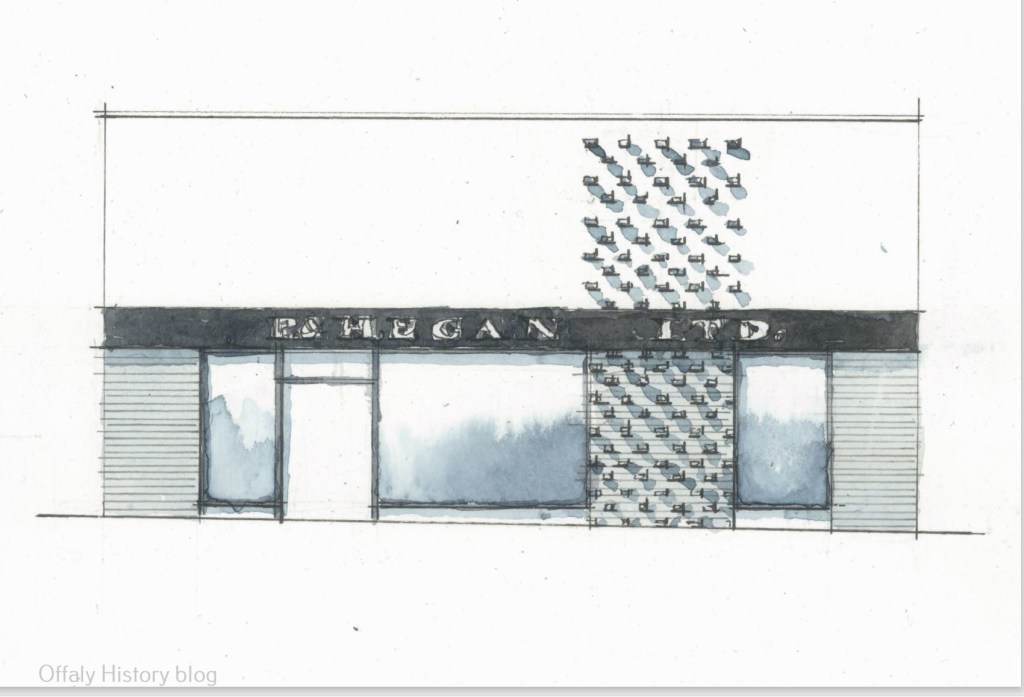

P&H Egan High Street 1961

The Tullamore born architect Paul Burke-Kennedy completed this striking shopfront on High Street for P&H Egan on a previously vacant site. Its simple form and use of unpainted concrete bricks as a finish, together with the contrast between the horizontal fascia and its Cowboy Font lettering with the vertical panel of projecting bricks, reflected the style of contemporary Danish architecture which was then very fashionable with the students of the School of Architecture in UCD of which Burke-Kennedy was a recent graduate.

In 1967 Burke-Kennedy designed the head office on Bury Quay of the Tullamore company Irish Mist. Consisting of two linked blocks it is another example of his skill in the use of brickwork. Its low-slung profile with a deep timber fascia and overhanging shingled roof suggest a Scandinavian influence also.

On his visit to Ireland in 1966, the influential English architectural critic Ian Nairn singled out the Egan shop as one of the few modern buildings of merit in the county.

’The less said about new buildings, the better. The best by a long way are the redecorated hotel interiors-entirely modern, sensitive, feeling like an Irish conversation. But their charm is almost impossible to photograph. There are occasional modest successes like Egan’s shop in Tullamore….’[1]

Over the following years the original shopfront was radically altered.

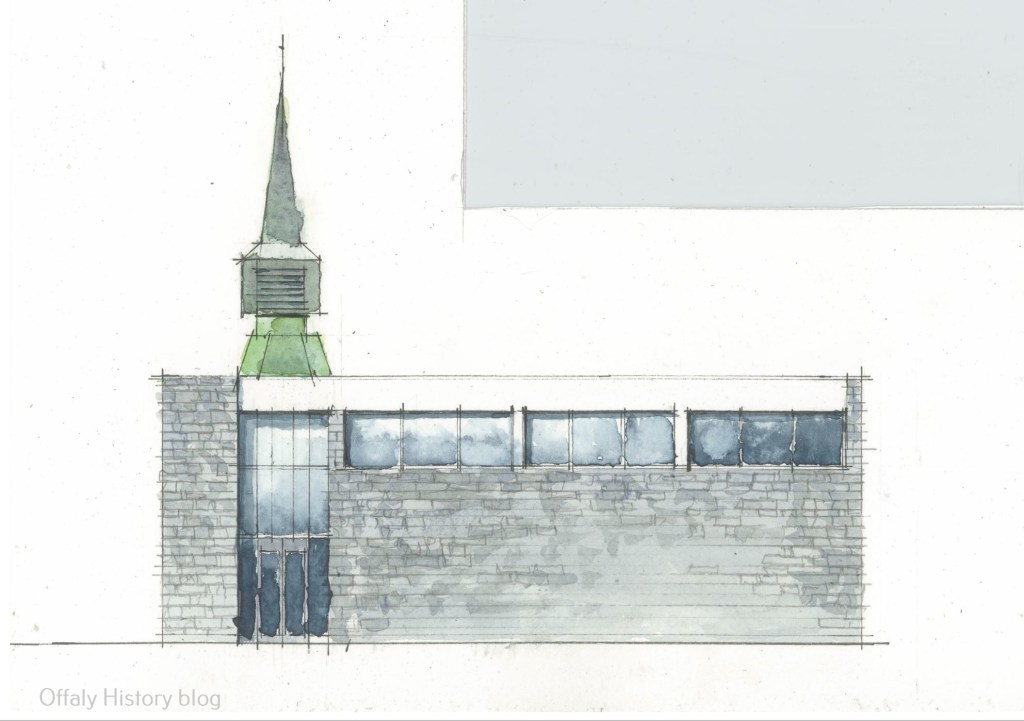

The Chapel of the County Hospital 1959

This elegant flat roofed rectangular plan building, with a first floor Oratory featuring high level clerestory stained glass windows, is finished in the same rusticated Ballyduff stone as the original 1937 hospital. Its architect Donald ‘Bob’ Tyndall had also carried out the Pearse Park and Marian Place housing schemes.

In this period, the design of Catholic churches was in a transition phase from neo-Gothic or Classical models to an acceptance of more modern modes, but no generally acceptable style had yet emerged. The Chapel is a simple almost industrial structure, and the only external indication of its religious function is the elegant fleche atop a casing for a church bell. It is an important contribution to the ecclesiastical architecture of the period.

Though a Protected Structure, its original setting, described in a contemporary account as standing in ‘well-kept lawns and floral borders’ has been subsumed into the expanding County Hospital.

Conclusion

As employment collapsed and emigration increased, the period from 1930 to 1960 seemed dismal and hopeless, yet for Tullamore it was an architectural Golden Age. The State provided superb social and educational buildings and excellent housing schemes which became springboards for the growth and prosperity that was to arrive in later years. High standards were pursued in the private sector also.

That important legacy deserved some recognition but sadly over the years all of the above buildings, including the original County Hospital and the Clontarf Road terrace, were demolished, compromised or are presently unprotected.

[1] ‘Ian Nairn, ‘The Bit in the Middle’ The Architects’ Journal, 7 September 1966.

Thanks to Fergal MacCabe for this article and the fine water colours.