At one time I didn’t think, but now I definitely do think, that the pleasantest way of seeing Ireland is from a seat in a bus. I do not mean one of those eight-day bus tours, conducted and excellent and comfortable as they may be, I mean the couple of hours spent bussing from one country town to another. [So announced Lennox Robinson in an article first published in the Irish Press and later in his compilation I sometimes think (Dublin, 1956). He would possibly have been amused to know that bussing has another meaning nowadays when students get together in a college dorm. Robinson was not inspired by some of the women who joined his Tullamore to Banagher and Birr bus. Now read on.]

If you travel in a friend’s car, you are cribbed and confined, he or she has to make talk with you and you have to return the ball of conversation; a train nearly always looks for and finds, the most poor and uninteresting country to travel through, and when it reaches an interesting town, Portarlington, for instance, is careful to stop a mile away from the place, John Gilpinish.

But a country bus swirls along, is very swift, and yet can be leisurely, picks up a parcel here and delivers a bundle of papers there.

We are, back in the old coaching days : the conductor knows everyone-or nearly everyone-and has a friendly word for each on-comer or down-getter. He sets down Mrs. Maloney at the Cross and helps an old Jack who is off to spend the day, his pension-day, in the town: yet he can be severe and inexorable on the question of accepting bikes.

I am beginning slowly to fall in love with the midlands slowly, because there is nothing tempestuous or flashy about them. The vivacity of Kerry and Donegal, the cuteness of Cork and Antrim-these are lacking, and instead there is a lovely autumn-afternoon placidity, golden and Veronese-woman-like atmosphere. The very names of sleepy; they are bees in August Lime-trees: Birr, Clogher, Ferbane, Clara, Mountrath.

When the country with difficulty rises to a range of mountains it does not call them harsh names like the Reeks or the Galtees, but thinks of the two most feathery, cotton-wool words possible ; it says ‘Slieve Bloom.’ Seen last Friday after lunch to a drift of Irish rain which suddenly swept across the landscape, helped by coffee and a wisp of ‘Irish Mist’-surely the most delectable of liqueurs[1] – the Midlands country grew more attractive every minute.

Compare these soft names with Carrick and Cork, with Wicklow and Belfast. Ugly crack-of-the-whip names. Names to make you get up at 7 a.m. and being in bed by 9.30.

If you know the Midlands and note the names I have written, you will understand that I am bussing from Tullamore to Birr. It is for a wonder, a lovely morning, and at long last they are cutting the wheat. It lies there, acres and acres of it, some cut, some starting this morning to be cut, some still untouched. Wheat seems to have stood up bravely to our cruel summer weather; oats lay down, and the crows tell me it has been one of the best autumns in their memory-and crows have long memories. There are a few things in colour more lovely than a great ripe wheat-field and the sun shining on it. Rossetti, describing his Blessed Damsel, said that ‘her hair that lay along her back was yellow like ripe corn’. But corn is not exactly yellow, it is-it is-there is a reddish tinge in it; there is a tinge of gold; in short, the colour of ripe corn is the colour of ripe corn, and no other words can describe it.

The bus is boarded and boarded again by middle-aged women. I have a penchant for middle-aged females, especially for old maids and widows, but these examples are utterly uninspiring. Their dress is ugly and careless, they have not bothered to put a comb through their hair – when did they wash it last? – they may have put a spit on their face, but certainly not a polish. But they are complacent and careless, so why should they bother.

Here in Banagher, and we by-pass the lovely Shannon Bridge and now we are in Birr. Compared with nice, tight, right Tullamore, Birr sprawls. But if it does sprawl, when it opens out in all its graciousness in John’s and Oxmantown Mall, can any other streets in a country town in Ireland be more completely satisfying? The spaciousness of those shallow doorways, the delicacy of the glazing! And that reminds me of a very characteristic feature of this Midland world; I mean the windows of small-pane of glass.

They seem to me to be entirely characteristic of Offaly, and thank goodness, even the modern building schemes (and how many and how good they are, mostly) copy them. Here and there in a small house, and a small shop, which is trying to be pretentious, the small-paned window has been torn out and a plate-glass one substituted, and you see how something which had character and beauty has been lost. It is as if a small, sparkling human eye had been exchanged for a large, cold, featureless glass one.

But it is three-thirty-five, and the bus back to Tullamore is leaving Emmet Square. The lovely morning has clouded, it is raining heavily and more heavily. The wheat cutting has been abandoned in despair, it is very sad.

Oh, for three weeks of hard dry weather. Scurry back to the rain to Tullamore’s hotel.

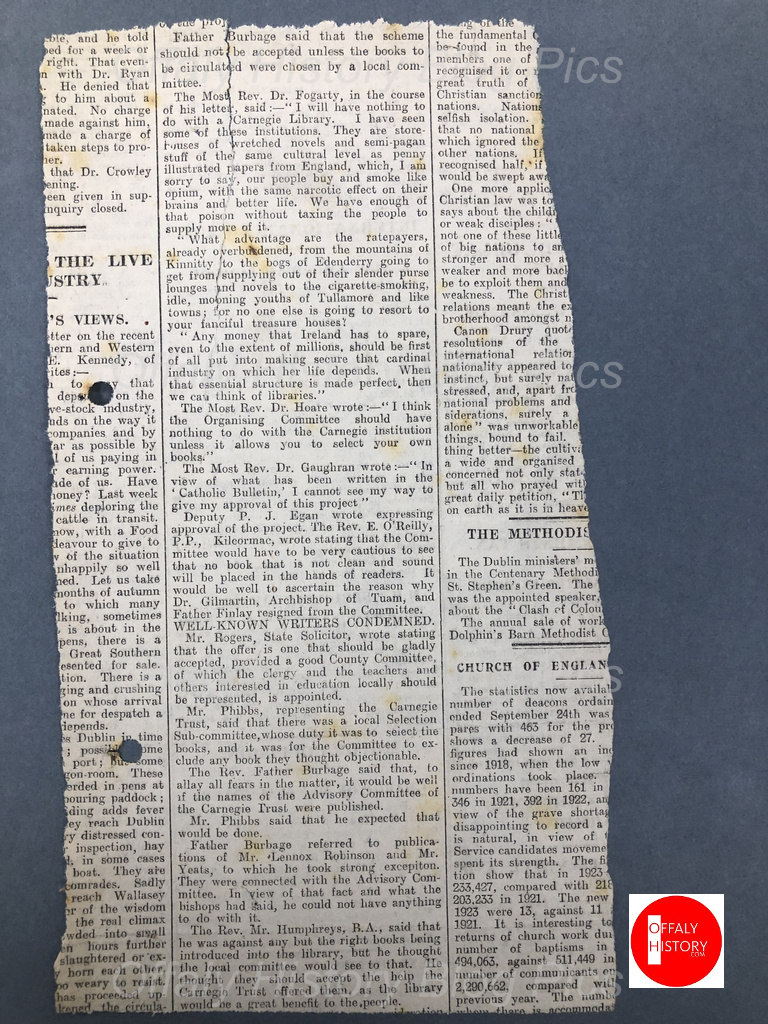

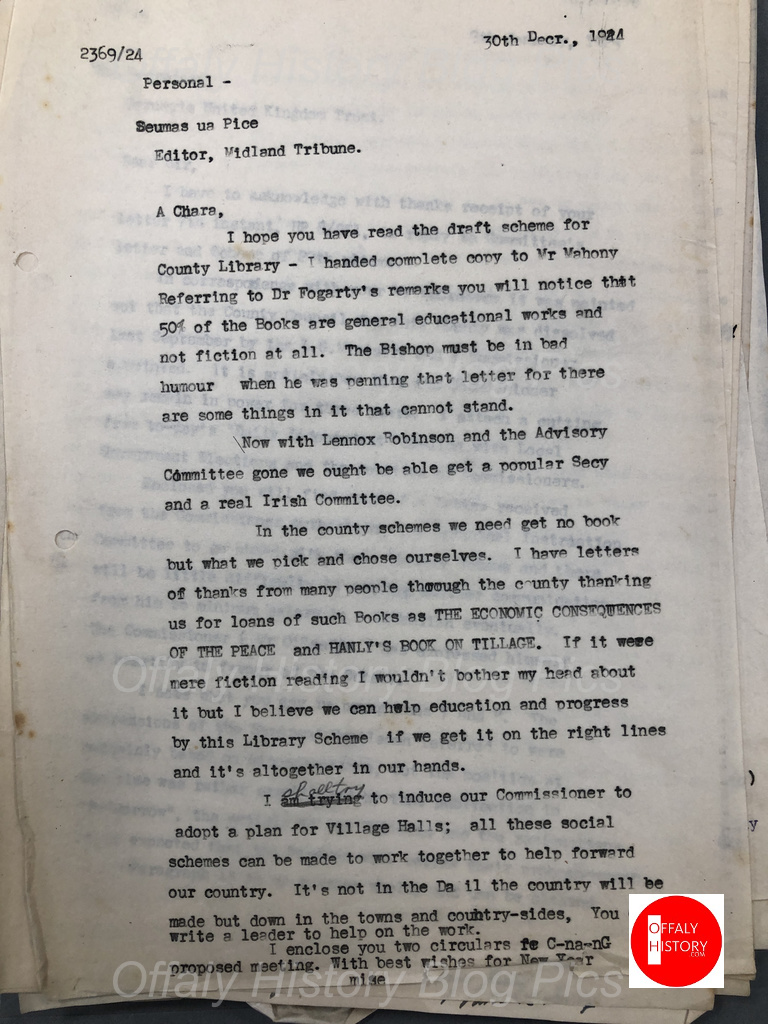

This extract is from Lennox Robinson’s I sometimes think (Dublin, published in October 1956), pp 50-2. The essays were mostly first published in the Irish Press. Robinson was no stranger to the midlands and worked on the setting up of the Carnegie backed Tullamore library in 1921 and would have helped with the Offaly County Scheme in 1925 but that he and the Carnegie Library Advisory Committee had been dumped at the behest of the bishops, especially Foley of Kildare and Leighlin and Fr Burbage of Geashill (Republican IRA) had difficulties – see news cutting attached

Chrisopher Murray writes in the DIB online:

. . In 1915 he took a position as organising librarian for the Carnegie (UK) Trust, then establishing a network of public libraries throughout Ireland. He remained with the trust until his dismissal in 1924 amid controversy over a short story he published in Tomorrow. In the meantime he continued to write plays, and won much success with ‘The whiteheaded boy’ (1916) and ‘The lost leader’ (1918). Like his play about Robert Emmet (qv), ‘The dreamers’ (1915), the latter was a political drama, in which Robinson imagines Charles Stewart Parnell (qv) alive and well and living in the west of Ireland in 1918. ‘The whiteheaded boy’ was Robinson’s first comedy and turned out to be his greatest success, being frequently revived on the Abbey stage.

In 1917 Robinson published his only novel, A young man from the south, which is autobiographical and emphasises the strong nationalist feeling also evident in some short pieces entitle Dark days (1918). But his genius lay mainly in the theatre and he returned to the Abbey in April 1919 as manager and producer/director, where he remained till his death in 1958. Robinson is usually credited with reviving the Abbey after 1919, encouraging the new talents of George Shiels (qv) and Sean O’Casey (qv) and building up perhaps the most talented acting company in the Abbey’s history. . .

[1] Irish Mist was made in Tullamore from 1947 to 1985. Offaly History published a history of this product and its people in 2023.