On the 1st of February, 1910, a Gaelic League nationalist died quietly in his home in Derrinlough House, Birr, County Offaly. Four days later, in An Claidheamh Soluis, he was briefly memorialised in print by Seán Ó Ceallaigh:

On Tuesday, Lá Fhéile Brighde, the first day of spring, Señor Bulfin was carried off by a sudden attack of pneumonia, before even his friends knew he was ill. The Gaelic League loses in him a great champion of its ideals, and the Irish of Argentina their leader… He was known and admired wherever an Irish class existed.

The name William Bulfin, in our time, does not live up to the description offered above, though it may well arouse some curiosity at the mention of an Irish Argentine. However, Bulfin, though his credentials remain firmly intact — An Irish nationalist, a Gaelic Leaguer who was present at the opening of the Argentine Gaelic League branch in 1899 and at many important league summits in Ireland — has largely fallen by the wayside in the discussion of Irish nationalist figures of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When reading the musings and sophisticated theses of Rambles in Éirinn, his seminal work, one realises that obscurity ought not to be the final resting place of this man of two countries, who loved both so well.

Author William Bulfin

Who was William Bulfin?

Born in 1864, William Bulfin was the fourth son in a family of nine boys and one girl. His father, William Bulfin Senior, was from Derrinlough (Derrin an Locha), Birr, while his mother hailed from Croghan. He attended a national school in Cloghan, where it is likely he was taught by the father of a future martyr of the 1916 Rising, Thomas MacDonagh.

Like so many others who would not inherit the farm and would therefore be unable to sustain themselves in their homeplace, William Jr. seemed destined for emigration. In 1884, he and his brother took the boat to Argentina. A strange destination, perhaps, but it is worth noting that the pampas of South America was the home of thousands of Irish emigrés, many from Longford and Westmeath in particular.

He worked on the ranches of the Argentine plains, specifically on that of Don Juan Dowling, a Passionist Father from County Longford. It was on this Estancia (ranch) that he met his wife-to-be, Anne O’Rourke from Ballymore.

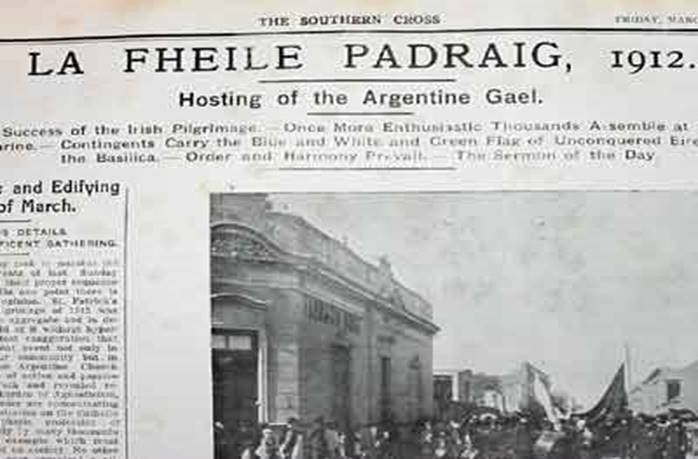

A keen observer and experient of the Gaucho way of life, he began writing for The Southern Cross, a newspaper based in Buenos Aires. Before long, he became the subeditor and subsequently the editor, eventually transforming the paper into a natural ally of the Gaelic League.

On Bulfin’s first return to Ireland, at a dinner hosted by the League, Pádraig Pearse is quoted as saying: ‘’There is no paper in Ireland that has done as much for the Irish language as The Southern Cross. There is no paper in Ireland that can compete with it.’’

Although a resident of Argentina for most of his life, William sent his son Éamonn to Pádraig Pearse’s school, St. Enda’s. A holistic educational project about which I have written here, Enda’s was a bastion of Gaelic nationalism, and influential figures in the revival were keen to send their sons to a school which they saw as readying Irish boys for the coming war for freedom. Éamonn would complete his schooling in Enda’s and would stay in Ireland to further his education in UCD, where he became captain of its Irish volunteer company. He was also recruited into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and condemned to death for his role in the Easter Rising, but was reprieved and deported back to Buenos Aires.

Irish Volunteers in Stafford prison in 1916. Éamonn Bulfin is third from left in the back row.

Back at The Southern Cross, William Bulfin was a constant voice of Argentine Ireland throughout the lead-up to the revolutionary period. However, he also steadily reported on life on the pampas, wrote travel pieces, short stories (many of which ended up in a now out-of-print collection, Tales From the Pampas) and, most significantly, the ‘rambling columns’ for which he his best known. They would eventually become what is now known as Rambles in Éirinn.

The Southern Cross, 22nd March, 1912

Rambles in Éirinn: Tearing Down English Ireland and Imagining it Anew

As Bulfin began to make regular trips to Ireland on Gaelic League business, an additional incentive for coming home revealed itself – cycling.

He bought a sturdy farmer’s bike and began to make long expeditions to every corner of the country. For each trip, he wrote a column and posted it back to The Southern Cross, where it would appear in print.

In these pieces, he traces the landscape in which he is travelling, interspersed with musings on Ireland’s troubled history, the implications of English rule, and proposals for a renewed Ireland. The rambles would likely be relatively unremarkable if it were not for Bulfin’s extensive knowledge of Irish history, not just in abstraction, but in relation to every place he set foot in. It is because of this knowledge that the rambles take on a kind of constructive quality, as Bulfin, ever the demolitionist but also the architect, identifies the ills of a given village, town or city, and proposes a way forward for it.

As for his mode of transport, it was all in the interest of taking the scenic route. On a tour into Northern Connacht, he remarks that the scenic route is, according to some, ‘uninteresting’, to which he retorts,

‘An uninteresting route?’ Not if you are Irish and know some of the history of your land and feel some pleasure in standing beside the graves of heroes and on ground made sacred by their heroism… then in the name of all the Philistines and seoiníní, take the train. (15)

This is representative of Bulfin’s views on Ireland on the most basic level, that it is, stunningly beautiful, ‘never is so beautiful as when the eye rests upon her face. You need never be afraid that you are flattering her while painting her from even your fondest memory’ (4).

Emphasising the singularity of the Irish nation is a constant trend in Bulfin’s writing. He laments that some can only conceptualise it in relation to places it is similar to, and others to which it is not. He implores us to ‘take it on its own merits’ and declares that ‘the practice of comparing one beauty spot on this earth with another is hackneyed and, in the abstract, somewhat sickening’. As the adage goes, comparison is the thief of joy, and for Bulfin, comparing Ireland to other countries, likening the hills of west Cork to the lake country or Limerick to Amsterdam, is doing Ireland a great disservice.

The Political and Cultural Vision of an Irish-Ireland

Underpinning Bulfin’s thought is a robust sense of national sovereignty. For centuries, the idea of an Irish nation, a distinct people and culture, now taken for granted, stood on unsteady ground after centuries of relentless anglicisation.

The assertion of an ‘Ireland united, Gaelic and free’ is not merely a catchy mantra from a Wolfe Tones song; it was – and is – the supreme ideological claim to Gaelic legitimacy, and for Bulfin, the rallying cry against British hegemony and normalisation; a reminder to the world that the torch of freedom and hope will always shine in the interest of Irish Ireland. Such was the view of Emmet, who demanded Ireland’s ‘place among the nations of the earth’. The young Irelanders, the Fenians, Pearse, Connolly, all believed in the inalienable right of Ireland to exist as a nation, culturally individual and self-governing; in the truest sense, Gaelic and free. Bulfin was no different.

When travelling through the ancient kingdom of Ossory, Bulfin happens upon an English motorcyclist making his way to Galway, a destination to which he required ‘the flattest, shortest and smoothest road’. Such a request upsets Bulfin, who challenges him, but to no avail. The motorbike man is adamant in his aversion to Ireland, unless, in the unlikely event that there is a ‘business possibility’ in taking a detour. This is the English colonial mentality that, in Bulfin’s eyes, has no place in Ireland. But other things have no place in Ireland. Bulfin was a fierce opponent of ‘snobbish Catholicism’, affirming that ‘the Irish nation must not be mutually distrustful and that it must not be sectarian’ (113). He attacks the schismatic Irish tendency to place one’s faith above one’s country, a position that has at best caused untold division, and at worst, acted as an excuse ‘for being political humbugs or avowed West Britons’ (117).

Bulfin sharply contrasts the West Briton mindset in Ireland with the prospective Irish national spirit. Emphasised here is the idea that such a spirit is alive in Ireland, bubbling beneath the soil, only needing to be reinvoked after centuries of suppression. It is worth noting that this national spirit is not based on tribal categories of religion or even ethnicity. As mentioned above, Bulfin held great disdain for the Catholics who stood with their faith at the expense of the nation. The Irish spirit is embodied by standing with Ireland first and foremost. Bulfin rousingly declares from the slopes of Wexford’s hills:

I like best to hear the name of IRISH given to the children of Ireland, who love her and give her the service born of love. Has not the gold of Gaelic and Gallic hearts been fused into an IRISH amalgam in the crucible of her woe! Let her sons and daughters, whether of Gaelic or Gallic extraction, have the honour of claiming her glorious name so long as their love is hers. And let the renegades be reviled as renegades, whether their blood be of the Gael or Gall (190).

A critic of home rule, Bulfin also cautions the Irish people against holding out false hope, against looking to Westminster for answers. Freedom, according to Bulfin, will only come ‘when Ireland, by her own effort, makes England fear her – and not until then’ (201). Central to the rambles is an ideology of perseverance in the face of the English’s many tricks and schemes. It seems no coincidence that perseverance of spirit is the topic of the day as Buflin cycles through Wexford and past Vinegar Hill, where the pikemen made their stand against all the odds for the sake of an Irish Ireland.

Conclusion

As alluded to above, generally speaking, the rambles follow a fairly simple formula: Bulfin takes a trip, he situates himself among the landmarks in the area: Croghan hill and the Sliabh Blooms marking high points of the midlands, the Galtees as the junction of Munster, Ben Bulben, the focal point of the Sligo coast, etc. He will then reflect on a historical event or person connected to the area, admire their greatness, identify modern problem areas, and use the national tradition and the spirit of optimistic rebellion to enter into deeper dialogue with the land. It makes for a cohesive end product: a short piece of usually no more than a dozen pages, which succeeds in giving one a feel for a particular area, its history, wounds, and people, always ending on a hopeful note, always looking towards the future to a new Ireland. This ability is really the essence of great travel writing.

His seminal work, Rambles in Éirinn, was republished in February of this year. It was a quiet launch, though accompanied by a wonderful Irish Times article by TK Moloney, which has no doubt played its part in recent months in shedding some light on the mysterious ‘Señor Bulfin’ of the Argentine pampas and the roads of Ireland. We can only hope that his image and legacy will continue to grow.

Works Cited

Breathnach, Diarmuid, and Máire Ní Mhurchú. “BULFIN, William (1863–1910).” Ainm.ie, 2025, http://www.ainm.ie/Bio.aspx?ID=599. Accessed 6 June 2025.

“Irish Midlands Ancestry.” Irlandeses.org, 2025, http://www.irlandeses.org/kiely.htm. Accessed 6 June 2025.

Ó Ceallaigh, Seán. An Claidheamh Soluis, 5 Feb. 1910.

Sisson, Elaine. Pearse’s Patriots: St Enda’s and the Cult of Boyhood. Cork University Press, 2004.

TK Moloney’s first of two articles on Bulfin will be published in this series on 10 October.

Supported by the Department of Culture Communications and Sport as part of the Commemorations Series for 2025.