You might wonder what was Library Hall used for before being transformed into 15 apartments in about 1995 with a new block of ten to the rear (PD 2824). Yes, some will recall when it was the county library and the happy hours borrowing books and perhaps sitting in the large windows or close to its pot-bellied stove in winter. That was almost fifty years ago. From 1923 to 1927 the building served as the first garda station in Tullamore. And before that: yes, it was the county infirmary or county hospital from 1788 to 1921. How many beds? It had 50 and thirty were generally in use. Budget was £2000 per annum by 1920. That might get you ‘a procedure’ now or a very ‘short stay’.

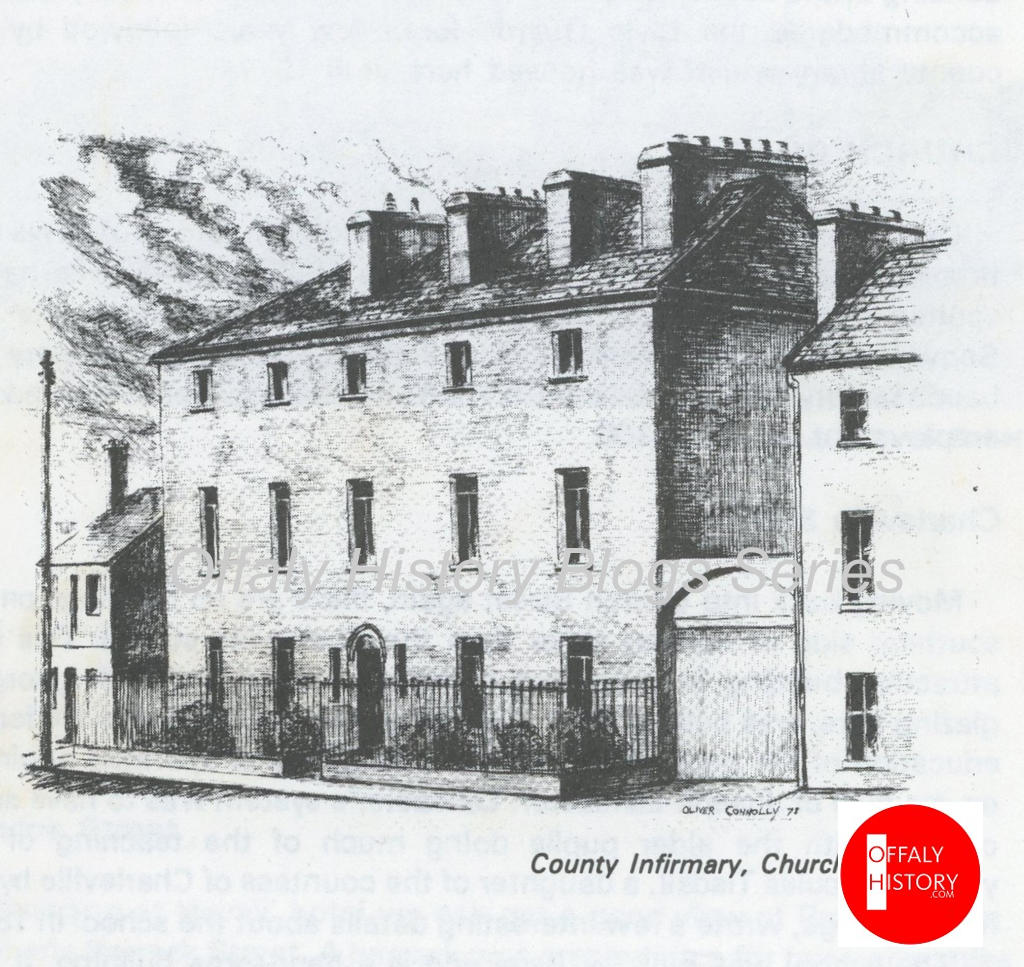

The building is of considerable architectural interest having three storeys, five bays and a tripartite doorcase. There is no doubt that the wide Henry Street (since 1905 O’Carroll Street) was designed so that the county infirmary would close off the vista at the western end.

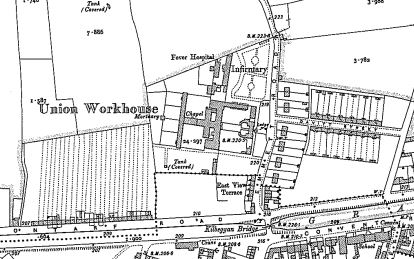

The infirmary is Tullamore’s oldest public building and was erected in 1788 and enlarged in 1812. The red brick house, formerly on the garden of the infirmary, and from the 1960s occupied by the Red Cross, was erected in 1915 at a cost of £879 to deal with incipient cases of tuberculosis.[1] After lying vacant for almost twenty years from about 1977 the large infirmary building was converted to apartments with only the façade and outer walls retained and a second block of apartments erected to the rear. Nonetheless, the building is assertive in form and scale and retains its stone doorcase and finely executed railings in a limestone plinth.

The county infirmaries owed their origin to an act of parliament in 1765 which provided for the establishment of infirmaries in most of the counties of Ireland.[2] The county infirmaries were financed partly by grants from parliament and the grand jury, and subscriptions from private individuals. The voluntary element of the funding had first to be raised locally before government grants could be secured. There was no provision for local support by way of raising a special rate and on-going funding was dependent on the mix of donations, local grand jury grants and a government contribution. Gifts were very acceptable and were needed to fund any significant improvements. Each infirmary was placed under the control of a board of governors. In order to become a governor it was necessary to make a subscription of twenty-one guineas in the case of life membership, or three guineas for members elected annually. The Church of Ireland bishop of the diocese and the rector or vicar of the parish in which the infirmary was situated were ex officio governors.[3] The governors were empowered to accept donations while each county grand jury was directed to subscribe annually not less than £50 and not more than £100. Each governor had the power of granting tickets of admission, but accident cases could be admitted without a ticket.

The infirmaries were a small affair and, in the context of need and difficulties of travel, could not hope to serve much more than the population in the town in which it was based and its hinterland to ten or fifteen miles. An infirmary’s extern patients could be drawn from a wider area and here the infirmaries could make a real difference by way of giving of advice and medicine, but the surgeons did not make domiciliary visits. The patients were those needing surgery and were usually short-stay rather than those with chronic illnesses or deemed incurable.

Offaly Archives has papers and some minute books for the county infirmary from 1867 to 1921. The surviving minute books (two) are somewhat formulaic. Also surviving are extern registers for 1837–8 and 1852–9 and certain registers of patients for the 1860s.[4]

The county infirmaries, unlike the workhouses of the late 1830s and early 1840s, were not built to any standard plan.

Howard reported on his visit to the old pre-1788 infirmary that it had six patients with two rooms on the first floor with five beds for men and three for women. The house was clean and quiet and proper attention paid to the patients. He noted at 19 April 1788 that the foundations for the new infirmary were laid.[5]

The new infirmary building of 1788 in Tullamore followed from the ’balloon fire’ of 1785 that damaged houses and the first Methodist chapel in the vicinity of the military barracks where the first infirmary may have been located. The new hospital was close to the old linen factory in what was to become Henry Street (later O’Carroll Street) and was designed to close off the vista whenever that street was completed – which was not until the 1840s. The new bridge at Church Road may have been completed in 1795 or earlier thereby facilitating a new access to Church Street from the Geashill road.

The infirmary, built on the Church Street site in 1788 for £490, was considerably enlarged in 1812 at a cost of £800 and this work may not have been started when seen by Atkinson of his visit to Tullamore in 1811. According to Sir Charles Coote, who published his Statistical Survey of the King’s County in 1801, the infirmary ‘is humanely attended to by Lady Charleville, and a machine for restoring life to persons apparently drowned, is now erecting at her Ladyship’s expense. So many fatal accidents that have occurred on the lines of canals for want of medical assistance, call for the universal adoption of this humane institution’.[6] The somewhat controversial judge, Baron Smith (1766–1836) of Newtown near Geashill (and now buried in the mausoleum in St. Mary’s churchyard, Geashill), was also active in support of the infirmary and very kindly offered to give 114 yards of good linen annually for the patients’ underwear so long as he approved of the management of the institution. Smith was a baron of the exchequer from 1801 and died in 1836.[7]

Tullamore in the eighteenth century was fatally subject to small-pox, fever and diphtheria and at a meeting in December 1776, arrangements were made for the general inoculation of the poor of the country. against such diseases as smallpox, fever and diphtheria. Presumably inoculation was carried out by ‘buying the pox’. It was claimed that inoculated smallpox was not only invariably milder than in a natural attack but that it was not infectious. The first recorded inoculation in Ireland was carried out by a Dublin surgeon in 1723. In an experiment carried out in Dublin in 1725 five children of a Dublin gentleman were inoculated: three recovered, but a ‘strong lusty boy’ and a ‘strong healthy boy who never had any sickness’ died.[8] By the 1800s it was known that persons who contracted cow pox had become immune to smallpox and thereafter vaccination with cow pox matter replaced inoculation., Dr Blakley, the infirmary surgeon inoculated 461 people from Birr and Shinrone and warned the wealthy that more needed to be inoculated to improve public health.[9] Blakley died in 1786 ‘deservedly lamented for his skill and indefatigable attention’ as the infirmary surgeon for many years.[10]

The improvements to the King’s County Infirmary building of 1812 could not have prepared it for the severe outbreak of disease in 1817–18. During that period the free school of Tullamore (the Charleville School across the street) was converted into a fever hospital, and there was also a building known as the House of Recovery. The minute books recorded that there was:

An outbreak of what is called malignant fever in 1818, lasting for upwards of three months, and necessitating the establishment of a temporary fever hospital and convalescent home. Additional medical attendance was also secured and a certain Dr Francis Benson was, on this occasion, paid the sum of £100 for having attended the fever patients “with the most persevering assiduity and skill”. In its early day ladies took an active part in the management of the infirmary, and the Countess of Charleville frequently presided at meetings of the Board.

A surviving report on the King’s County Infirmary of 1824–5 confirms that 366 patients were admitted in the year end to 6 January 1825, eleven died in that period, and that 8,506 extern patients were treated. The report for King’s County was largely prepared by Francis Berry, the agent to the earl of Charleville from about 1820 up to his death in 1864. Berry particularised the annual expenditure in 1824 of almost £900 including that of the salary of Surgeon George Pierce at £120, and the other eight staff combined at little more than the same amount. The diet relied more on bread, milk, oatmeal and pudding with potatoes comprising about 30 percent of the expenditure on food.[11] Pierce had been appointed as county surgeon in 1817 and survived until 1859. He was succeeded by his son-in-law Dr John Ridley, who lived at Moore Hall.

Interestingly, the position of physician at the Tullamore workhouse(opened in 1842) was held by members of the Moorhead family from 1842 until the death of George Moorhead in 1934, while the surgeon at the infirmary was held by George Pierce and his Ridley son-in-law, and other Ridley family members, from 1817 up to 1906. It does seem that the appointments of medical men and apothecaries were on confessional lines with RC men, Moorhead and Quirke, in the workhouse and Anglicans, Pierce and Belton, in the infirmary. John Ridley had applied for the workhouse position in 1842 but it was awarded to Moorhead. The governors of the infirmary would ensure that Protestants were appointed to the senior positions. That changed with the introduction of the county and urban councils in 1899.

Surgeons at the King’s County Infirmary, 1767–1921

1767–1786 Dr Blakely

1786 (?)–1817 Joseph B. Tabuteau

1817–1859 George Pierce

1859–1875 John Ridley

1875–1888 James Ridley

1888–1906 George Pierce Ridley

1906–1921 Timothy Meagher

A noted case within a year of the infirmary closing was that of Sergeant Cronin (RIC) who was shot on 31 October 1920 by the local IRA. He was leaving his house in Henry/O’Carroll Street when he was shot at close range and was taken to the nearby infirmary where he died early the following morning.[12]

It was decided to close the Offaly County Infirmary (the name was changed by the county council in June 1920) in July 1921.[13] The decision was part of a general attempt to reform the poor law system in operation since 1838 and identified by the many Sinn Féin councils throughout the country as an example of British misrule in Ireland. The arguments advanced for closing were that the Offaly County Council had of necessity to economise and to cater for all ratepayers in the county. Tullamore between 1842 and 1921 had two hospitals – that at Ardan Road, Tullamore was financed by the poor law rate chargeable on the Tullamore Poor Law Union, and the county infirmary was on the county at large but serving for the greater part patients in the Tullamore union or Tullamore rural district. This was obviously an injustice to the ratepayers of the county who because of geographical isolation derived no benefit from that county institution. Besides it was reckoned that the running cost of the infirmary was too high. That seems doubtful given the small annual budget.

Did the amalgamation of the services save money? According to the evidence of the county secretary into the state of finances and services of the county council in 1924 the amalgamation of the health services did not save any money.[14] The council was dissolved in August of that year and a commissioner appointed for four years. It was all a long way from the expectations of the revolutionary administrators of early 1922.

For more about the county infirmary see the forthcoming issue of Offaly Heritage 13.

[1] Midland Tribune, 21 Oct. 1922.

[2] Pierce Grace, ‘Patronage and health care in eighteenth-century Irish county infirmaries’ in Irish Historical Studies, vol. 41, no. 159 (May 2017), pp 1–21.

[3] See Poor Law Inquiry (Ireland), Appendix B, containing general reports upon the existing system of public medical relief in Ireland; local reports upon the dispensaries, fever hospitals, county infirmaries and lunatic asylums; with supplements, parts 1 and 2 containing answers to questions from the officers etc of medical institutions, B.P.P. 1835 (369) xxxii, app. B to First Report, p. 24.

[4] Offaly Archives: The records held are described as follows and see http://www.OffalyArchives.

INF 2/1: Registers of patients

INF 2/1/1: Extern Patient Book September 1837 – February 1859 (excluding 1839 – 1852).

INF 2/1/2: Register of Patients May 1861

INF 2/1/3: Register of Patients October 1863 – October 1864

INF 2/1/4: Register of Patients June 1867 – September 1868

INF 2/2: Minute Books

INF 2/2/1: August 1888 – June 1919 (excluding April – December 1916).

INF 2/2/2: June 1919 – August 1921

INF 2/3: Annual Reports

INF 2/3/1: 5 May 1896 – 6 January 1897 (1 page).

INF 2/3/2: 5 January 1897 – 6 January 1898 (1 page).

[5] John Howard, An account of the principal lazarettoes in Europe with various papers relative to the Plague: together with further observations on some foreign prisons and hospitals; and additional remarks on the present state of those in Great Britain and Ireland (London, 1789), pp 86–7, 94.

[6] Charles Coote, Statistical Survey of the King’s County (Dublin, 1801), p.178.

[7] See the entry for Smith in DIB, vol. 8, 1034–5, entry by Bridget Hourican.

[8] For a recent article on vaccination see Laurence Geary, ‘Vaccination in Ireland: the evolution of a process’ in History Ireland, 29:6 (Nov.-Dec., 2021), pp 28–31.

[9] Pierce Grace, ‘Patronage and health care in eighteenth-century Irish county infirmaries’ in Irish Historical Studies, xli:159 (May 2017), p. 14 –citing Freeman’s Jn., 8 Apr. 1777.

[10] Volunteers Journal, 17 Mar. 1786.

[11] Returns of Establishments in Ireland for the Reception, Maintenance or Relief of the Poor. RIA: Ref: RR/41/F/25 Printed June 1825. King’s County return prepared by Francis Berry.

[12] Michael Byrne, ‘The killing of Sergeant Cronin’, Offalyhistoryblog.wordpress.com, 2 March 2019, 31 October 2020; Michael Byrne, Tullamore in 1916 (Offaly History, 2016), pp 252–55.

[13] Midland Tribune, 2 July 1921.

[14] Offaly Independent, 2 Aug. 1924.

Supported by the Heritage Council as part of its Living in Towns series.