This month we begin a series of articles on the history and heritage of the Grand Canal in County Offaly that will run to upwards of 50 blog articles in 2024 and have its own platform on our website, http://www.offalyhistory.com. Our aim is to document the story of the course of the canal from the county boundary east of Edenderry to Shannon Harbour in the west. Today the Grand Canal is one of the greatest amenities that County Offaly possesses and we want to tell the story, and for readers to contribute by way of information and pictures. All the material will be open to be used on our website and the format will allow for editing to improve and to receive additional information from you the reader, which will be acknowledged. So Buen Camino as we make our journey through a quiet and well-watered land. The year 2024 marks the 120th anniversary of the completion of the Shannon Line at Shannon Harbour and may also see the completion of the canal greenway in this county.

Grand Canal project agenda

- The canal from its reaching Offaly in the 1790s to its completion at Shannon Harbour in 1804 had a profound impact on the local economy and local landscape. Initially it provided a transport service for goods and people that continued until the coming of the railways in the early 1850s. Thereafter it continued as an important carrier of goods traffic until 1960. From the 1940s (and earlier) the use of the canal for leisure traffic was appreciated and written up by several travellers. Its use as a linear park for recreation was realised in the 1970s and lately has received a significant boost with the promotion of cycleways, walking and fishing – all summarised as Greenways.

- This story will focus on the place-name history along the stages on the line of the canal and how the new watercourse impacted on and is of importance to the local landscape as a heritage amenity.

- What role did the canal place in the development of Offaly’s towns and villages and in the provision of new streets and houses?

- The canal’s role in the communications revolution with passenger and goods traffic.

- The building heritage of towpaths, bridges, locks, lockhouses aqueducts, viaducts and culverts.

- The accounts of journal and travel writers on the canal since the 1800s.

- The canal in books and films

- The stories of boatmen, lockkeepers, fishermen, walkers, rowing clubs.

- Good Friday 1998 and the management of the canals as an All Ireland undertaking.

- The unique mapping record

- The photographic record

- Other reference works

Why is the Grand Canal so important?

The construction of the Grand Canal revolutionised transport in Ireland as a whole, and in Offaly in particular. In the early eighteenth century road transport was still at a very rudimentary stage of development, ensuring that the Grand Canal on its completion was in a position to dominate travel to and from the country. Most importantly, it allowed for the speedier transportation of goods, thereby facilitating trade in the area and the transfer of raw materials such as grain, malt, stone, brick and turf.

As early as 1664, the acting Viceroy in Ireland, the Duke of Ormond, considered the question of inland navigation as a means towards improving communication within the country. However, it was not until 1751 that the Board of Inland Navigation was established. Work commenced on constructing a canal which would connect Dublin with the River Shannon and the River Barrow in 1756.

In the early years the building of the Grand Canal was beset by difficulties. Bad planning and bad engineering ensured that the first twenty miles of the canal cost twice as much as had been forecast and had proceeded at a ridiculously slow pace. Fifteen years after the commencement of construction, Dublin Corporation found that it had no funds remaining to finance the canal – to such an extent that they were even unable to extend the canal as far as the Bog of Allen.

The first actual excavation for the canal was made in 1756. The name for the new waterway was borrowed from the famous Grand Canal of Venice and similarly the fine bridge near Kilmainham (although officially named Harcourt Bridge) was by popular acclaim called Rialto Bridge, owing to its fancied resemblance to the Rialto in Venice.

With the proposed scheme floundering after huge expenditure for little return, a group of nobles and businessmen formed the Grand Canal Company in 1772 and with John Traill as their engineer and William Jessop as a consultant they raised sufficient capital to proceed with the project. In 1779 the canal opened for twelve miles, and by 1791 Athy had been reached. By 1793 the canal had reached the outskirts of Edenderry and by 1797 it had progressed as far as Philipstown (Daingean), and then in 1798 it finally reached Tullamore. Tullamore was to remain the canal’s terminus for six years during which time the foundations were laid for substantial growth in prosperity in the town and led eventually to Tullamore taking over the role of county town from Philipstown in 1835.

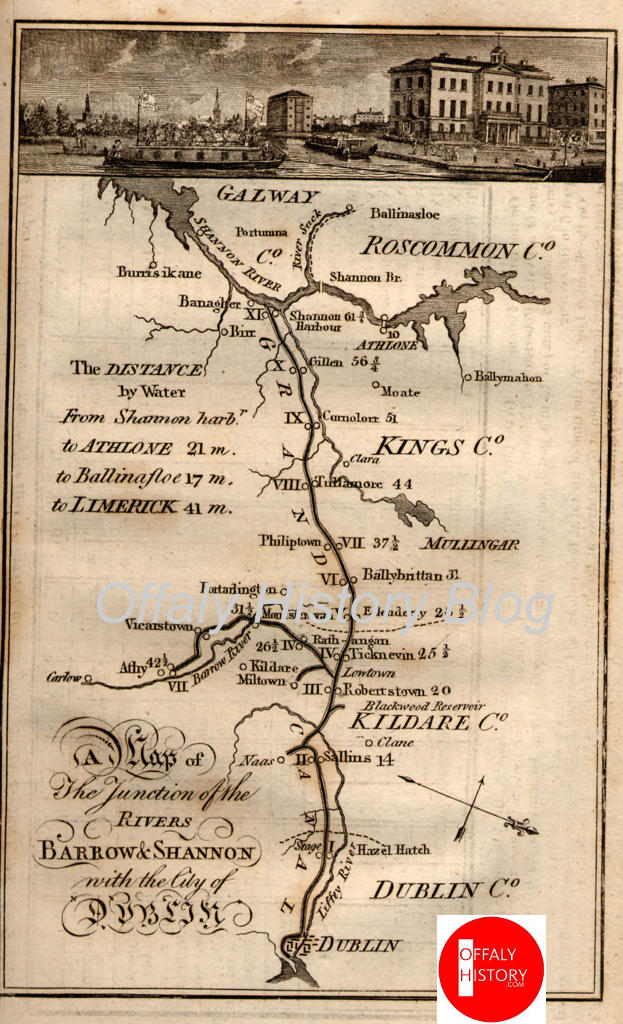

In 1804 the canal reached the Shannon at Shannon Harbour and branch lines were later extended to Corbally in 1811; to Ballinasloe in 1827; to Mountmellick in 1830; and to Kilbeggan in 1834. In all, the construction of the waterway marked a considerable engineering achievement with many novel difficulties overcome, such as the passage over a bog near Edenderry through the use of the high embankments. Including the canalised portion of the Barrow from Athy to St. Mullins, the total length was 206 miles. It had 64 locks, 35 water supplies and 139 bridges. The stretch as far as Athy estimated to cost £98,000 actually took £427,000 to complete. The total cost of constructing the whole system was £2,000,000.

At first travel from Dublin to Tullamore took almost fourteen hours and amongst the first passengers to use the route were British soldiers on their way to fight French troops who had landed in Killala Bay, County Mayo in May 1798. By 1834 the introduction of ‘fly boats’ had cut the length of the journey to less than nine hours – which was considerably shorter than the time required to complete the trip over land.

The commercial advances brought by the canal at Edenderry will be dealt with in another blog, but among the immediate developments at Tullamore (1800–01) were the establishment of a hotel, stores, a collector’s house and a dry-dock at Tullamore under the supervision of builder Michael Hayes all of which opened in 1801.

With the county also bordered by the River Barrow and the River Shannon, the area is now idyllic for pleasure cruising and other water-based activities. Indeed, environmental tourism along the canal is proving one of the most profitable routes forward for business in the area – a departure which would be a fitting memorial to the foresight of the earliest developers of the waterway.

The lockkeeper, Mr Pender, at Ticknevin, about c. 1976. The late Michael Hensey of Tullamore to the left

[1] John Warburton, James Whitelaw and Robert Walsh, A history of the city of Dublin, two vols, London, 1818.

Enough of the overview for this week. Next week we look at the expected outcomes of a new transport system as seen by General Vallancey in 1771 and how he expected it to impact on Offaly’s towns and villages on the route of the proposed Grand Canal line

Response

[…] Offaly History Blog has announced that they will be publishing a series of 50 articles in 2024 about the Grand Canal in […]

LikeLike